Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme Inger Andersen asserted disputes on the landmark plastic pollution treaty did not mean failure, despite negotiations remaining inconclusive.

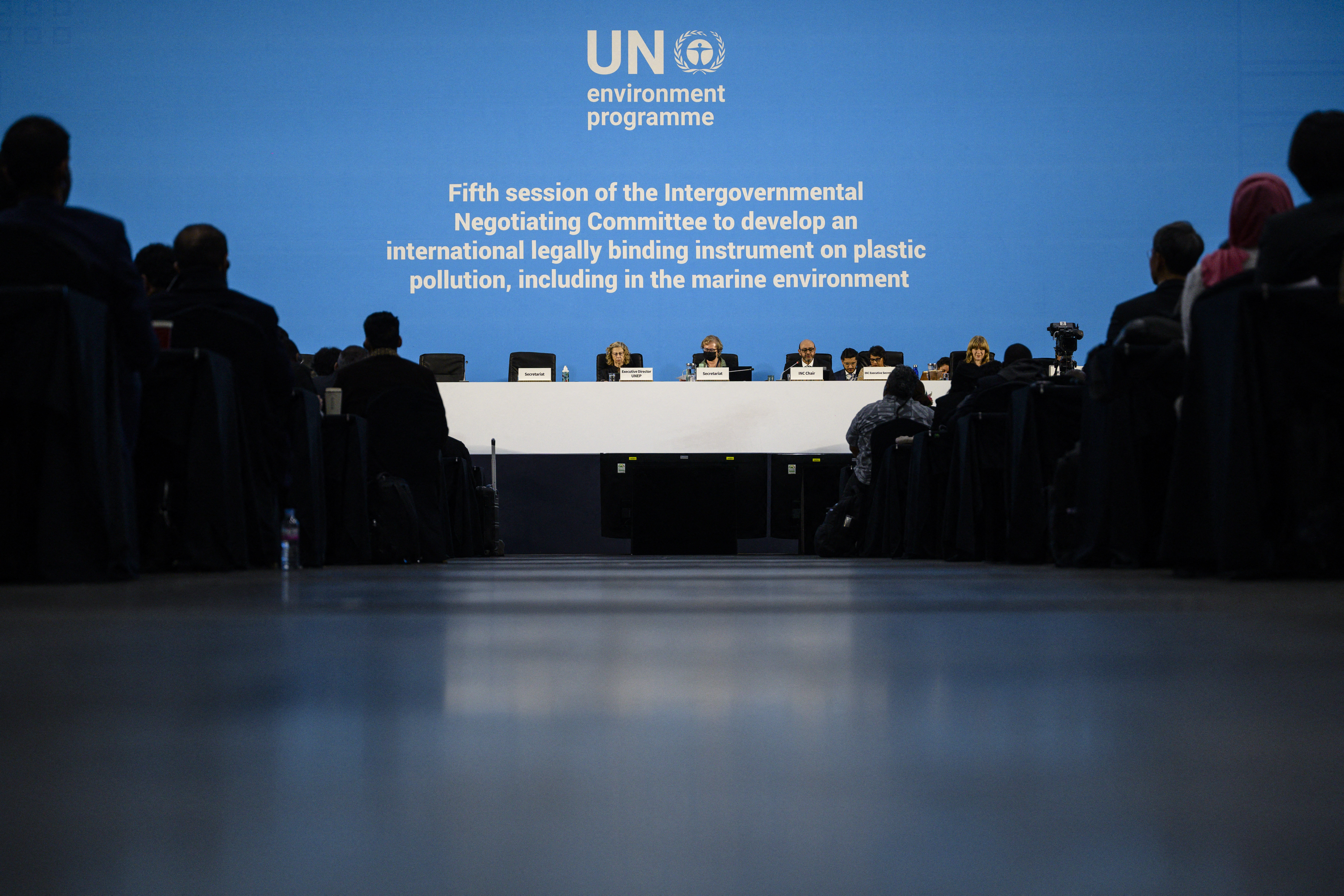

"What we do have is very, very good progress," Andersen, said on negotiations in Busan, South Korea. Nearly 200 countries spent a week in discussions starting on Nov. 25, aiming to agree on the world's first treaty to curb plastic pollution.

Over 90% of plastic is not recycled and millions of tonnes of plastic waste litter the environment each year. But in the early hours of Monday morning, negotiators effectively conceded defeat, acknowledging that they had failed to bridge serious divisions over the aims of the treaty.

Dozens of countries pushed for an agreement that would set targets to limit new plastic production and phase out certain chemicals and single-use plastic products. However, this proposal was strongly rejected by some nations, including Saudi Arabia and Russia, which argued that the treaty should not include any reference to production. This group mainly consists of oil-producing countries that supply the fossil fuels used in plastic production.

The disagreement stymied progress through four rounds of talks preceding Busan, resulting in a draft treaty that ran over 70 pages and was riddled with contradictory language.

The diplomat chairing the talks sought to streamline the process by synthesizing views in his own draft text, which Andersen said represented a step forward.

"We walked into this with a 77-page long paper. We now have a clean, streamlined ... treaty text," she said. "That forward movement is significant and something frankly that I celebrate."

But even the revised text is full of opposing views, and countries insisted that all parts of it would be open to renegotiation and amendment at any new round of talks. That led environmental groups to warn that extending the so-called INC-5 talks to INC-5.2 risks simply repeating the deadlock seen in Busan.

Andersen acknowledged that deep differences remain and "some significant conversations" are needed before any new talks. "I do believe that there's no point in meeting unless we can see a pathway from Busan to the treaty text being gavelled," she said.

The final plenary of the talks saw dozens of countries back new production targets and phasing out chemicals believed or known to be harmful. "A treaty that lacks these elements and only relies on voluntary measures would not be acceptable," Rwanda's Juliet Kabera said.

But Saudi Arabia's Abdulrahman Al Gwaiz indicated that production cuts remain a red line for many nations. "If you address plastic pollution, there should be no problem with producing plastics, because the problem is the pollution, not the plastics themselves," he said.

Andersen said it was clear that "there's a group of countries that give voice to an economic sector," but added that finding a way forward was possible. "That's how negotiations work. Countries have different interests, they present them and the conversations then have to take place ... seeking to find that common ground."

No date or location has yet been set for resumed talks, though Saudi Arabia and others sought to restart no sooner than mid-2025.

Andersen said she remained "absolutely determined" to win a deal next year. "Sooner is much better than later because we have a massive problem."