Which institution comes to mind if we say that 75% of the more than 2 million artifacts in the collection of one of the world's greatest cultural archives come from different countries? Of course, the British Museum.

For a long time, it has been at the center of debates over returning artifacts, particularly those taken from Türkiye and Greece, as well as other countries.

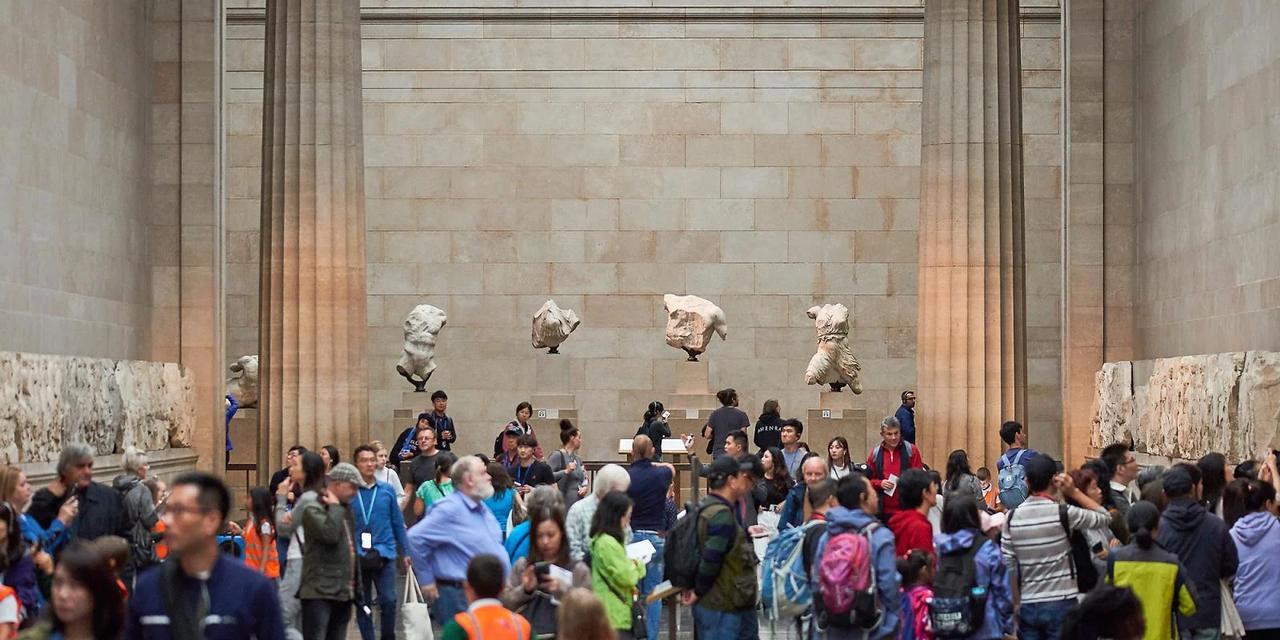

Since the museum houses a vast number of artifacts, many people question how many of them are actually connected to the United Kingdom. While the British Museum's collection includes pieces from all over the world, discussions about the return of objects such as the Parthenon Sculptures have reignited interest in this issue.

It is often claimed that if the British Museum were to return all the artifacts it allegedly took from other nations, it would be left empty. Statistically, this claim appears to be accurate. Artifacts taken from countries such as Iraq, Italy, Egypt, and Türkiye outnumber those originating from the United Kingdom.

Of the more than 2 million cataloged artifacts in the museum, only around 650,000 are linked to the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). According to unofficial sources, the museum reportedly stores over 8 million artifacts. Interestingly, the British Museum has cataloged only half of its collection online, and approximately 80,000 objects are accessible to the public.

Türkiye, frequently at the center of repatriation debates, has had 75,434 artifacts taken to the British Museum. Some of the most remarkable sections of the museum are the galleries between halls 15 and 23, where artifacts from Türkiye’s ancient cities are displayed. Among these, two halls are entirely dedicated to artifacts brought from Mugla.

The remains of the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, are exhibited in Hall 21, which is named after it. The Nereid Monument gallery houses other artifacts brought from Xanthos, an ancient city in present-day Türkiye's Mugla.

Upon entering the British Museum, visitors are greeted by two lion statues placed at the main entrance. Those passing by these lions, which were excavated from the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos, and walking toward the Queen Elizabeth II Great Court at the center of the museum will see the Knidos Lion, a statue measuring approximately 2 by 3 meters.

The British Museum’s Islamic Art section also contains artifacts collected from across the Islamic world. Among the pieces sold to the museum by a so-called "donor" named Edward Beghian is the sword of Ottoman Sultan Selim III.

The “Islamic World” hall, which features Ottoman art and culture, includes tiles from the Cinili Hamam, a structure in Istanbul designed by Mimar Sinan. The collection also houses ceramic items donated by collector John Henderson after his death, as well as artifacts acquired by Augustus Wollaston Franks, one of the museum’s first curators.

Additionally, the British Museum contains many historical artifacts from Türkiye, including the bronze head of Aphrodite found in Gumushane, the statue of King Idrimi discovered in Hatay, and numerous other archaeological objects.

Greece, a frequent focal point of repatriation debates, has contributed approximately 66,000 artifacts to the British Museum. However, some of the museum’s most famous pieces—including the Parthenon Sculptures, the Rosetta Stone, and statues from the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos—have fueled heated discussions on the restitution of cultural heritage.

The Parthenon Sculptures, also known as the Elgin Marbles, have been at the center of a long-standing dispute between Greece and the U.K. Lord Elgin, the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, took these sculptures to the UK in the early 1800s, claiming he had permission to remove them in order to "preserve" them. However, critics argue that they were essentially displaced during Britain's colonial era. This debate resurfaced in recent discussions between U.K. and Greek leaders, with Greece demanding the sculptures' return.

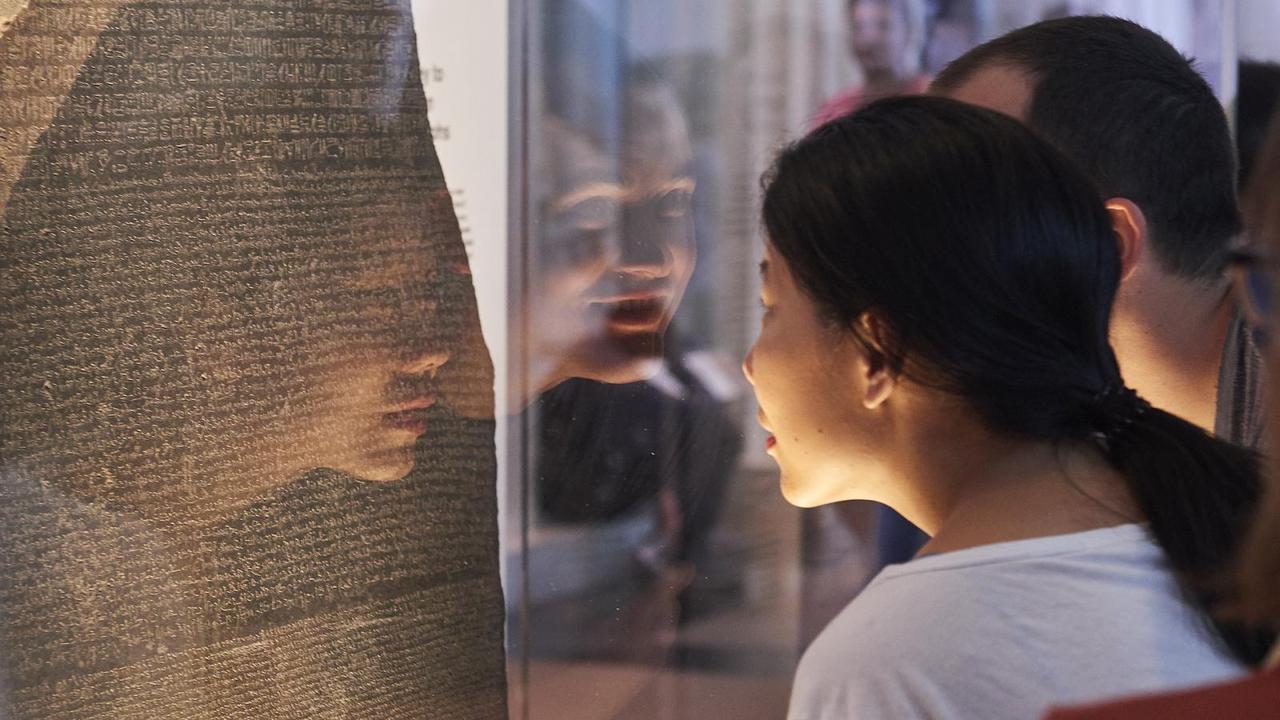

One of the most famous objects in the British Museum is the Rosetta Stone, which has been at the heart of an ongoing dispute between the U.K. and Egypt. The stone was discovered during Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign in the late 1700s and was later handed over to the British under the Treaty of Alexandria in 1801.

Egyptian activists have repeatedly called for the Rosetta Stone's return, arguing that it is a symbol of Western colonialism.

The British Museum’s stance on repatriation has come under increasing scrutiny, with multiple countries demanding the return of artifacts taken under controversial circumstances.

For example, Nigeria has called for the return of the Benin Bronzes, sculptures and royal regalia seized by British forces during the 1897 invasion of Benin City. Meanwhile, Ethiopia demanded the repatriation of objects displaced by the British military during the 1868 campaign in Maqdala.

Despite these calls, the British Museum insists that its collection is not just about preserving history but also about fostering global dialogue.

The museum claims to have positive relationships with countries such as Nigeria and Ethiopia and remains open to discussions regarding the future of repatriation.

Here is a breakdown of the number of artifacts from various countries housed in the British Museum:

| Country | Number of Artifacts |

|---|---|

| Iraq | 164,315 |

| Italy | 148,814 |

| Egypt | 120,904 |

| France | 82,224 |

| Türkiye | 75,434 |

| Germany | 67,172 |

| Greece | 66,000 |

| U.S. | 65,621 |

| China | 61,138 |

| India | 53,824 |

| Iran | 50,806 |

| Japan | 42,725 |

| Netherlands | 16,508 |

| Scotland | 14,763 |

| Cyprus | 14,062 |

| Spain | 13,202 |

| Ireland | 12,146 |

| Austria | 9,661 |

| Belgium | 9,509 |

| Russia | 9,175 |

| Wales | 7,506 |

| Croatia | 4,417 |

The ongoing debate over the repatriation of cultural artifacts reflects a broader shift in how the world views colonial histories and the legacy of the empire. As global discussions continue, one question remains: How much of the British Museum’s collection truly belongs to Britain, and what should be returned to its rightful home?

The British Museum’s role in the repatriation debate continues to evolve, reflecting the complex relationship between cultural heritage, historical context, and the legacy of colonialism.