Istanbul, a city straddling continents and centuries, has witnessed remarkable demographic transformations shaped by imperial ambitions, industrialization and economic shifts.

Istanbul's population history offers a window into how governance, migration, and cultural dynamics have shaped one of the world's most storied metropolises.

From the Ottoman Empire's deliberate strategies to the rapid urbanization of the Republic era, Istanbul's evolution was the product of resilience to challenges.

To understand Istanbul's population evolution, it is essential to go back to the period of its conquest in 1453. Mehmet Dilbaz explained that during the conquest, the city had a population of approximately 10,000, and after the fall of Constantinople, more than half of the residents fled.

"The once-grand capital of the Roman and Byzantine Empires had become a ghost town with barely 5,000 people," Dilbaz noted. Istanbul, which had served as the capital of great empires, was now almost deserted, resembling a ghost town.

Fatih Sultan Mehmet's vision to establish a universal empire required transforming Istanbul into a vibrant and populous city. "Fatih Sultan Mehmet first focused on reconstructing the city and then crowned it with a new population," said Dilbaz.

To achieve this, the sultan relocated populations from various parts of Ottoman territories.

The Ottoman Empire's strategy for repopulating Istanbul extended beyond Muslims. "Artisans and craftsmen from various parts of the empire, including Armenians and Jews who fled persecution in Spain, were invited to Istanbul during the reigns of Fatih Sultan Mehmet and his successor Bayezid II," explained Dilbaz.

These efforts created the foundation for Istanbul's cosmopolitan structure.

Istanbul's population was diverse and carefully managed to ensure balance. During the late reign of Yavuz Sultan Selim and throughout Kanuni Sultan Suleiman's rule, a protected population policy was introduced.

"Individuals needed a 'murur tezkeresi,' or travel permit, to enter and settle in Istanbul. The government's goal was to maintain the city's cultural and demographic integrity," Dilbaz explained.

This controlled approach to Istanbul's population persisted into the late Ottoman period. Dilbaz highlighted that "By Sultan Abdulhamid II's reign, the population remained stable, and even through the 1930s and 1940s, the numbers were largely preserved."

However, some key events disrupted this stability. The 1934 Thrace pogroms and the establishment of Israel in 1948 led to the emigration of approximately 20,000 Jewish residents of Istanbul.

Dilbaz emphasized the unique approach to integrating ethnic groups into Istanbul. For example, Poles fleeing Russian aggression in 1839 were settled in Polonezkoy (Adampol).

"Rather than assigning them land in central Istanbul, the state provided farmland in Beykoz, previously owned by Jesuit priests," he explained.

By contrast, Circassians fleeing Russian atrocities in 1864 were welcomed into the city without restrictions, reflecting the cultural and religious ties they shared with the Ottoman population.

The mid-20th century marked a turning point in Istanbul's demographic history. Dilbaz detailed how the city transitioned from an imperial center to an industrial hub under the Henry Prost Plan of the 1930s.

"Initially, the plan aimed to preserve Istanbul's unique character, but by the 1950s, it was repurposed to support industrialization," he said.

Industrial facilities were built in areas like the Golden Horn and Kagithane, regions the Ottomans had deliberately kept free of heavy industry.

This transformation, supported by Marshall Plan aid, attracted waves of internal migration.

"Traditional Istanbul residents unaccustomed to factory work were replaced by workers from rural Anatolia," Dilbaz remarked. As a result, the city's population surged from 800,000 to over 2.5 million within a decade.

During the Republic era, Istanbul's overall growth reflected Türkiye's broader urbanization trends. In 1927, Istanbul's population was just 700,000. By 1950, it had crossed 1 million, and by 1980, it reached 4.5 million.

The 1980s and beyond saw unprecedented urbanization, with the population rising to 13.2 million by 2010. By 2023, Istanbul housed 15.66 million people, marking it as Türkiye's largest and most dynamic city, though recent years have seen a slight population decline because of reverse migration and economic challenges.

The rapid population growth created housing challenges, leading to the proliferation of informal settlements. "Anatolian migrants, unfamiliar with urban living, established shantytowns in peripheral areas like Zeytinburnu, Umraniye and Gultepe," said Dilbaz.

Conversely, migrants from the Balkans, accustomed to city life, integrated more seamlessly into historic districts such as Fatih.

By the 1980s, these informal settlements had evolved into densely populated neighborhoods, highlighting the impact of rapid rural-urban migration.

As Istanbul became Türkiye's economic powerhouse, it attracted migrants from across the country, with Sivas, Kastamonu, and Ordu among the top provinces contributing to the city's population.

Istanbul's demographic evolution reflects a delicate balance between growth and heritage. The Ottoman sultans' strategic population policies aimed at creating a vibrant, cosmopolitan city, while the Republic's industrialization efforts transformed Istanbul into a modern metropolis.

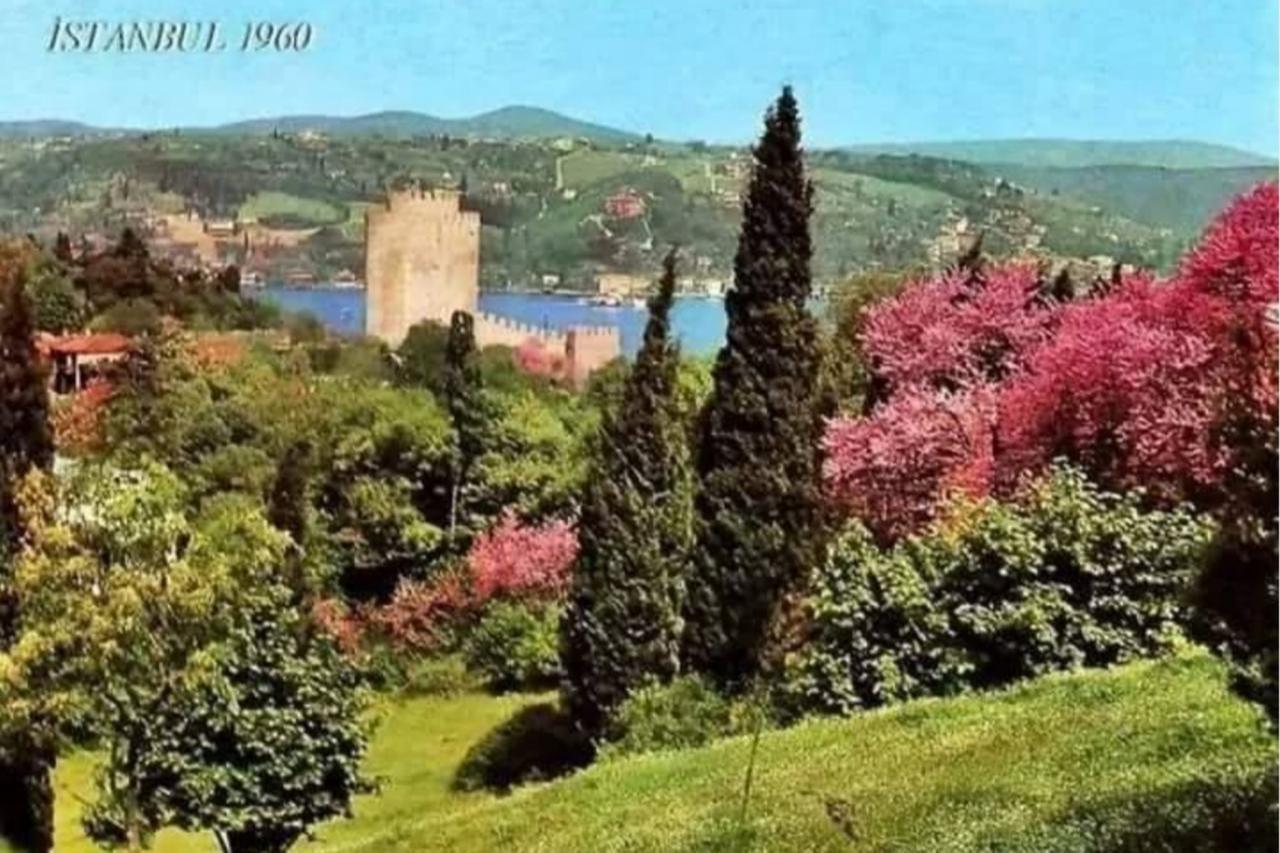

However, this growth often came at the cost of the city's traditional structure and natural environment.

Rising living costs, traffic congestion, and limited green spaces have also contributed to a growing trend of reverse migration, with residents seeking quieter and more affordable alternatives.