In an exclusive interview, Professor Yilmaz Selim Erdal, a renowned anthropologist, sheds light on the shocking discoveries at the Iznik (Nicaea) Roman Theatre in, Bursa, Türkiye, a site that revealed unsettling evidence of cannibalism during the First Crusade.

The excavation, which began in the 1980s under the leadership of Bedri Yaman, has uncovered a complex history of human activity, burial practices, and violent confrontations that point to a dark chapter of history.

The excavation of Iznik Roman Theatre, initially believed to be a Roman concert hall, has revealed a wealth of human remains spanning several centuries.

Professor Erdal explains that the site’s transformation, from a Roman theatre to a cemetery, and later a military base, reflects the changing cultural dynamics in the region. Thousands of human remains, including those of adults, children, and warriors, have been uncovered, providing evidence of the social and military life of the time.

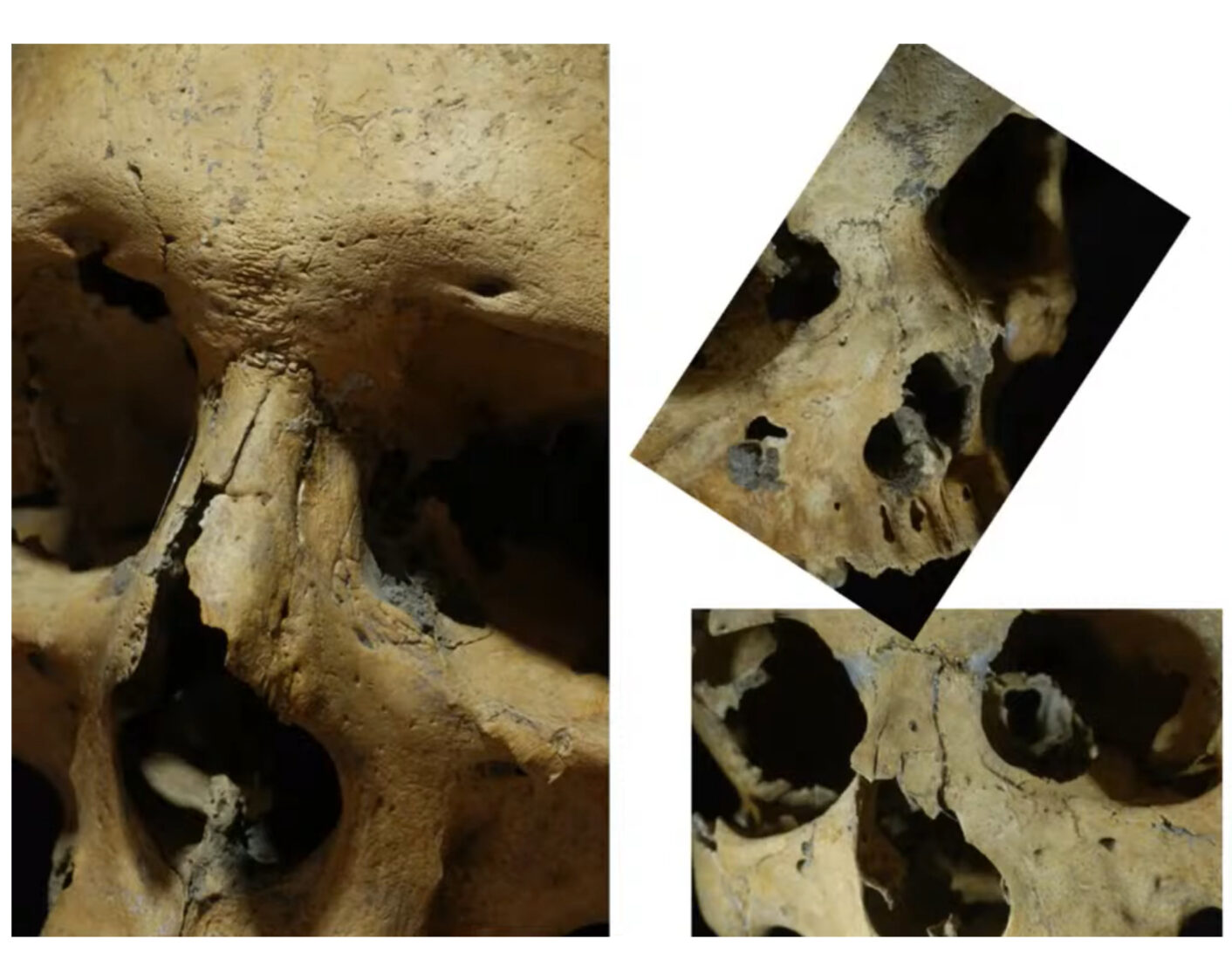

The bones reveal disturbing signs of violent conflict, with many individuals suffering from sword or spear wounds, particularly to the skull and face. Some remains show signs of punishment, suggesting that many individuals may have been involved in warfare or high-status military roles, potentially linked to the Byzantine army.

Among many signs of torture, it is evident from the holes in the skulls and the groin areas that the victims' heads were likely severed from their bodies, impaled on a spear, and thrown down from the walls. This is depicted in medieval illustrations and is also visible on the bones. Additionally, methods of torture like crucifixion can be clearly understood from the nail marks found on the bones of the hands and feet.

Among the most unsettling findings is evidence that points to the practice of cannibalism during the First Crusade. Professor Erdal shares that historical accounts have long mentioned the extreme conditions of the Crusader army, especially during the Siege of Nicaea in 1097, where soldiers turned to consuming human flesh.

Anna Comnena, who lived between 1083 and 1153, says in the 10th chapter of her book "Alexiad": "… they either maimed the babies in their mothers' arms or impaled them on spits and roasted them over the fire ..."

In his haunting historical account “The Crusades,” French historian Frantz Funck Brentano paints a grim picture of the brutal savagery of the Crusaders. The narrative includes passages that describe the horrific brutality of the Crusaders, who became so savage that they would cook and eat the Turkish children they killed.

Brentano also quotes chilling lines from the “Chanson d’Antioche,” a national epic regarded by the French, stating: “The Crusaders would skin the corpses of Muslims, remove their intestines, and then cook and eat their flesh. One day, Hasmetmeap Pierre L’Ermite was standing in front of his tent. King Tafur arrived with his men. Most of his people were dying of hunger. The king addressed him, ‘Out of your holy mercy, give me advice, for we are dying of hunger.’ Pierre L’Ermite replied, ‘This is due to your cowardice. Take the dead Turkish bodies that have been thrown about; if they are cooked and salted, they will be very pleasant to eat.’ King Tafur said, ‘You are right, Your Holiness.’

Then the Crusader soldiers came out of their tents. They skinned the Turks, removed their internal organs, boiled the meat in water, and then ate it. Upon seeing this, there was not a single Turk whose eyes did not shed tears. The soldiers were saying to each other, ‘Here comes Fat Tuesday, the last day of Carnival. This Turkish meat is better than fatty ham and smoked pork…’ When there were no more Muslims left to skin, they would dig up graves, remove the corpses, pile them together, separate the bones, and dry them in the wind to prepare them for eating.”

When the army reached Nicaea, they were defeated by the Turks and forced to retreat. Cut off from their food and water sources, the Crusader army resorted to this method to feed themselves. Other sources, such as Richard le Pelerin and William of Malmesbury, confirm that Crusaders turned to eating human flesh during their campaigns. According to Abbasid sources, that in all the epic literature of the Arabs, the Franks are consistently depicted as man-eaters.

While definitive proof is difficult to establish, several skeletal remains discovered at Iznik show unusual markings. Cuts on forearm bones and bite marks from animals suggest that these individuals may have been subjected to cannibalism, possibly by the Crusader forces during their retreat from Nicaea.

Professor Erdal explains that the markings appear to be consistent with descriptions of cannibalistic practices documented in historical texts, further supporting the possibility that these acts were carried out as a survival mechanism during times of extreme starvation.

The excavation findings also offer significant insights into the genetic history of the region. Professor Erdal discusses how genetic studies of ancient skeletons from Iznik reveal a mix of populations from Anatolia, the Caucasus, and Europe, reflecting the dynamic population shifts of the time. This mix is particularly notable among the Crusader army, which, as Professor Erdal explains, had ties to both Byzantine and European forces.

The strategic importance of Iznik during the Crusades cannot be overstated. The city’s fortified walls, military significance, and religious role as a center of Christian doctrine made it a focal point during the Crusader campaigns. According to Professor Erdal, these findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the Crusader's impact on Anatolia, with Iznik acting as a critical battleground between Christian and Muslim forces.

Professor Erdal concluded that the evidence uncovered at Iznik provides crucial data for historians seeking to understand the brutal realities of the Crusades. The practice of cannibalism, while shocking, was not isolated to this region and was, in some cases, a response to the dire conditions faced by soldiers. Through these discoveries, Iznik offers a new perspective on the human experiences during one of history’s most tumultuous periods.

The findings at Iznik, supported by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TUBITAK) and ongoing academic collaboration, continue to challenge our understanding of the First Crusade and offer a sobering reminder of the extremes to which humanity has gone in times of war.