The Cemka Hoyuk site, located in southwestern Türkiye near the upper reaches of the Tigris River, has yielded an extraordinary find – a 12,000-year-old burial that might belong to a female shaman.

The discovery, published in the journal L'Anthropologie by associate professor Ergul Kodas, head of excavations at Turkish mound, and his team, shed light on the spiritual roles and rituals of early hunter-gatherer societies during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) period, which dates between 10,000 and 8,800 B.C.

“The remains of a woman buried with a variety of wild animals at a critical point in human history may suggest that she played an important spiritual role,” reads the article in National Geographic.

The remains of a woman, estimated to have been between 25 and 30 years old at the time of her death, were found buried beneath the floor of a mud-brick building at Cemka Hoyuk.

This practice of burying the dead under living spaces was common during the PPNA, but the presence of a large limestone block covering the burial site is an anomaly.

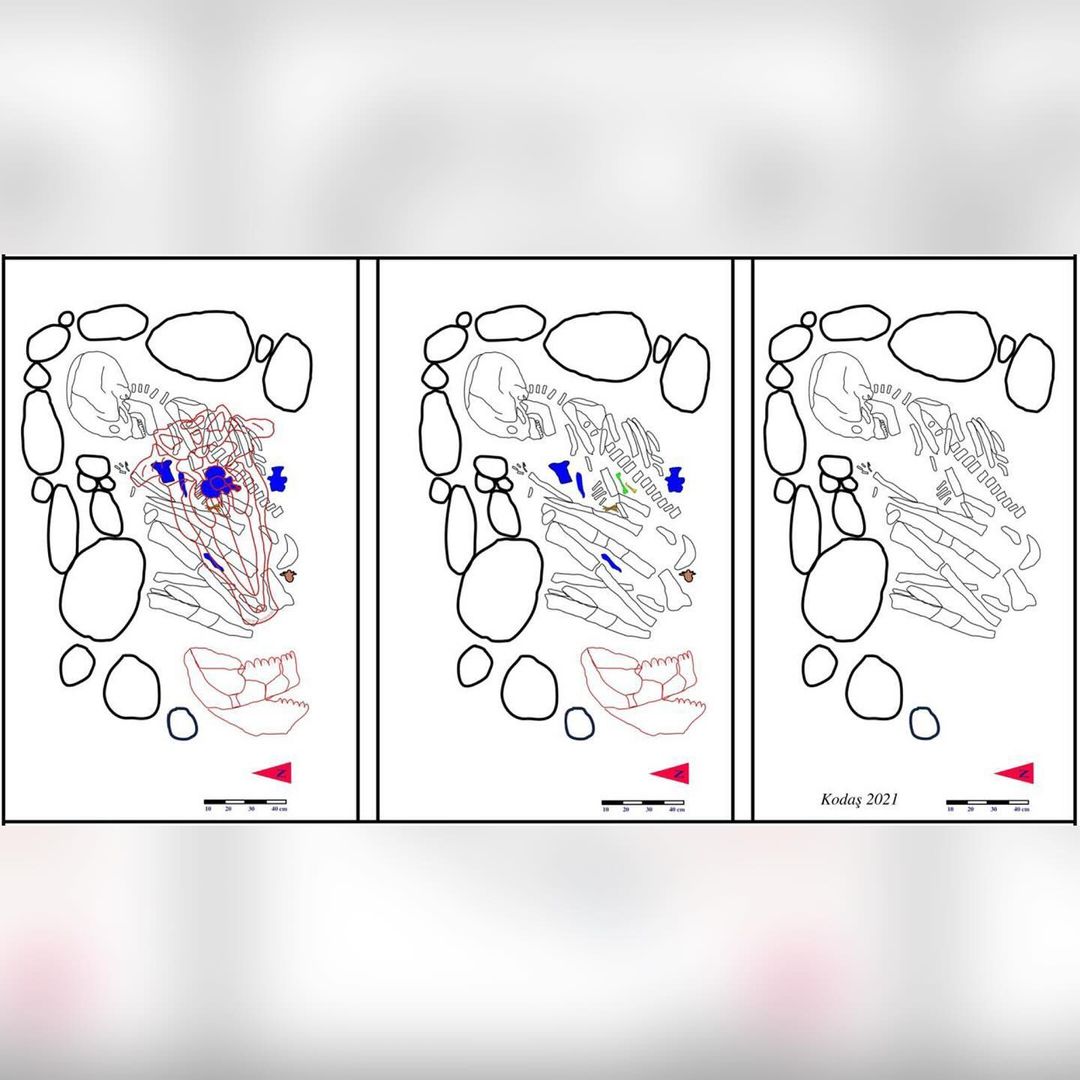

The grave contained the skull of an aurochs (a primitive ox), along with other animal bones including the wing of a partridge, the leg of a marten, and the remains of a sheep or goat.

These wild animals, which predate the domestication of farm animals, suggest that the woman may have held a significant role in her society, potentially connected to the spiritual or ceremonial use of these creatures.

The PPNA period was marked by a transition from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to more settled forms of living. During this time, early settlements like Jericho and Gobeklitpe began to take shape.

Gobeklitpe, located about 241 kilometers west of Cemka Hoyuk, is known for its elaborate stone pillars and carvings, indicating the emergence of complex ritual practices.

The Cemka Hoyuk burial site’s unusual features have led researchers to speculate that the woman might have been a shaman – a practitioner believed to communicate with spirits.

Ergul Kodas, who led the study, notes that the inclusion of wild animal bones could signify a ritualistic or spiritual significance, possibly tied to early shamanistic practices.

The concept of shamanism, as understood in modern contexts, might not fully capture the role of individuals in the PPNA era. Bill Finlayson from the University of Oxford suggests that while the term "shaman" is used for convenience, it might not accurately describe the spiritual roles of ancient practitioners.

He compares this find to other significant PPNA burials, such as that of a woman in Israel’s Hilazon Tachit cave, who was interred with various animal remains, indicating a potential link to ritual practices.

Steve Mithen of the University of Reading posits that the social and environmental changes during the PPNA period likely intensified the importance of individuals capable of mediating between the seen and unseen worlds.

This period of experimentation with new ways of living may have heightened the role of spiritual leaders or ritual practitioners.

Thomas Levy from the University of California San Diego emphasizes that this discovery contributes valuable insights into the evolution of early settled societies from hunter-gatherer groups. The involvement of women in these early spiritual practices, as suggested by the Cemka Hoyuk burial, challenges and enriches our understanding of gender roles and ritual importance in ancient communities.

Kodas noted that the animal bones found in the burial exhibit clear similarities with shamanic burial traditions observed in other traditional societies.

"It should also be noted that animal bones found in Near Eastern burial contexts might have been left in connection with funerary meals," he said.

"We can interpret the relationship between the animal bones and the individual through two main concepts. The first is the possibility of a connection to a funerary meal (particularly with cut marks). The second is that the symbolic concepts attributed to these animals by the community could be related to shamanistic phenomena in the burial of an individual with a special status. This grave can be interpreted as the result of a shamanistic act in an analogical symbolic context, but it is difficult to definitively state this," he added.

As researchers continue to explore the significance of these findings, they offer a profound glimpse into the complex spiritual lives of our ancestors and the pivotal role of ritual in shaping early human societies.