Anatolia, a historic region bridging East and West, is renowned for its rich tapestry of civilizations – from the Hittites and Phrygians to the Greeks and Romans.

Its storied past is mirrored in its extensive archaeological treasures, which continue to fascinate historians and archaeologists.

As we delve into October 2024, Türkiye’s archaeological landscape has once again revealed remarkable insights into its ancient heritage.

This month has been particularly significant, with groundbreaking discoveries that illuminate various facets of ancient life across the region.

From elaborate burial sites to intricate mosaics, each find adds a new chapter to our understanding of Anatolia’s profound historical legacy.

Here are the top 12 archaeological discoveries made in Türkiye in September 2024, showcasing the region’s timeless allure and its pivotal role in the narrative of human civilization:

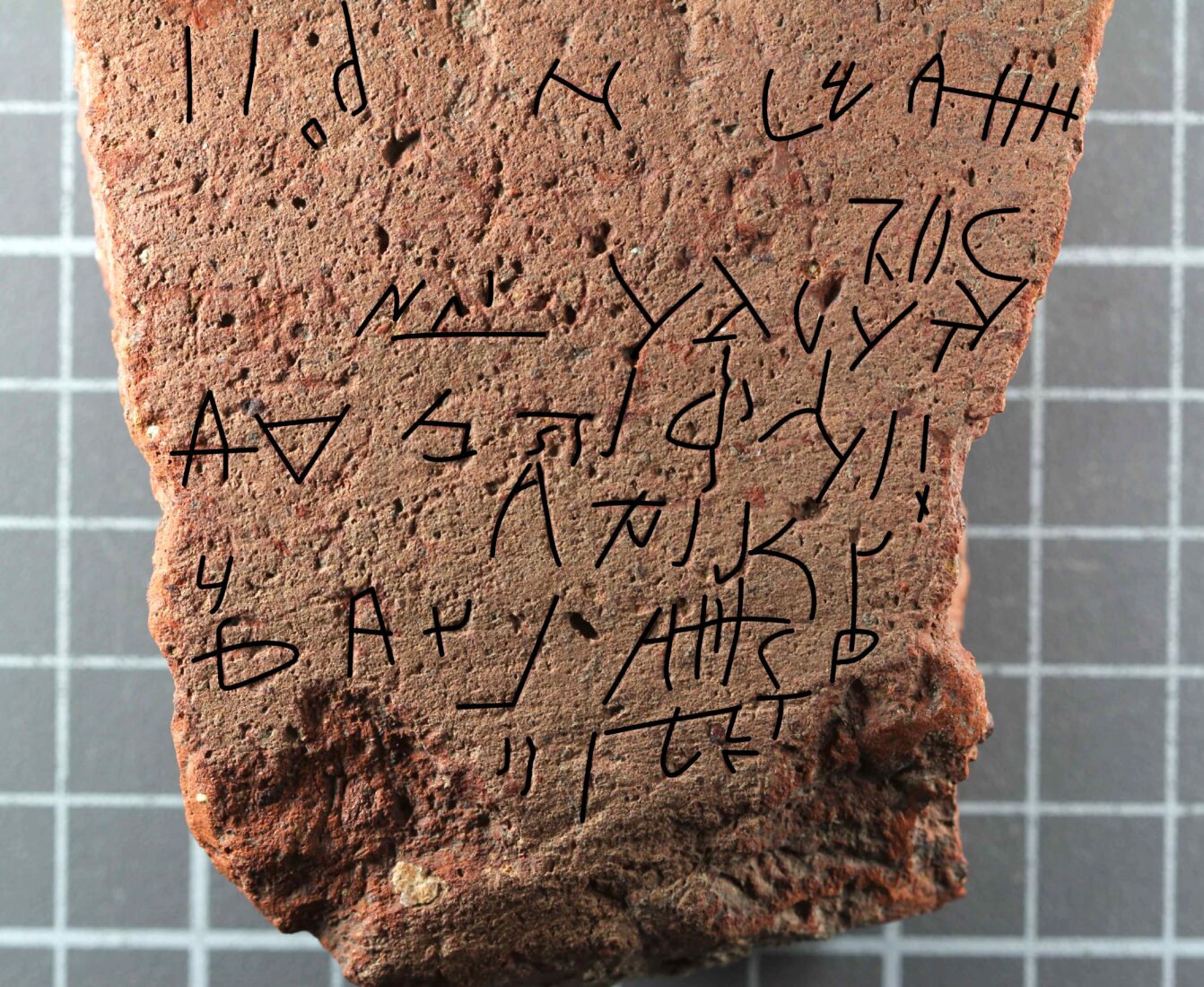

A recent archaeological excavation at Silifke Castle in Mersin has unveiled a remarkable Byzantine "protective tablet," believed to have been crafted to safeguard structures and graves from malevolent forces.

This significant finding, revealed on September 3, 2024, adds an intriguing dimension to the site's historical narrative.

The protective tablet, part of the ongoing 13th phase of excavations led by professor Ali Boran from Ankara Haci Bayram Veli University, was uncovered during work around the castle’s mosque. Initial analyses suggest the tablet served a purpose akin to modern "nazar boncugu" or protective charms, indicating the site's historical significance.

Professor Boran emphasized the tablet's relevance to both regional and Anatolian history, suggesting it points to the existence of grave sites within the castle, which had not been identified previously.

The inscriptions on the tablet hint at its function to ward off all forms of evil and enemies, showcasing a tradition of protective practices that has persisted since antiquity.

As excavations continue, the tablet is expected to contribute significantly to the understanding of Byzantine history and the cultural heritage of the region.

In an exciting discovery, archaeologists excavating Oluz Hoyuk in Goynucek, Amasya, have unearthed a 2,600-year-old fire altar that belonged to the Medes, who ruled the region around 600 B.C.

This find, announced on September 6, 2024, marks a significant addition to the archaeological record of the Medes in Anatolia.

Professor Sevket Donmez, leading the excavation, explained that the altar's square shape and modifications signify its sacred nature within Median religious practices.

This altar is crucial as it provides the first archaeological evidence of Median presence in the region, including unique architectural elements.

The fire altar, transformed from a Frig altar, illustrates a pivotal shift in religious practices from polytheism to early Zoroastrianism.

Donmez noted the Medes' close ties to the Persians, highlighting the significance of this find in understanding the broader context of religious transformations in ancient Anatolia.

Ongoing excavations are expected to yield more insights into the Medes’ influence and presence in the region.

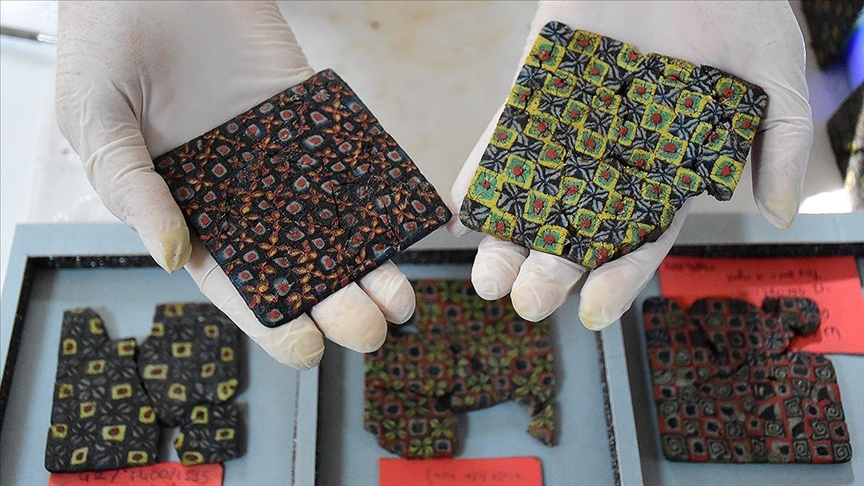

In a groundbreaking discovery, archaeologists have uncovered Millefiori glass panels during excavations at the ancient port city of Andriake, part of Myra in Antalya, Türkiye. This significant find, revealed on September 8, 2024, showcases the intricate craftsmanship of the fifth and sixth centuries A.D.

The panels, crafted using the Millefiori technique, reflect the luxurious decorative practices of the era. Minister of Culture and Tourism Mehmet Nuri Ersoy hailed the discovery as one of the year's most important, emphasizing the panels’ role in shedding light on Myra's artistic heritage.

Professor Nevzat Cevik, head of the Myra-Andriake excavation team, noted the rarity of such glass techniques in Türkiye, highlighting the panels' unique floral designs. Discovered near the agora, the panels were initially fragmented but have now been reconstructed into 20-30 complete pieces, with more ongoing.

In a remarkable archaeological discovery at Ayanis Fortress in Van's Tusba district, three bronze shields and one helmet, estimated to be 2,700 years old, were unearthed during ongoing excavations. This site, built by the Urartians, has been under excavation for 36 years, with the latest efforts led by Professor Mehmet Isikli of Ataturk University.

Professor Isikli reported the artifacts were found about 6-7 meters below the surface in a chamber likely untouched by ancient earthquakes.

The bronze shields are believed to have been ceremonial, while the intricately decorated helmet suggests royal or religious significance.

To date, over 30 bronze shields have been found at the fortress, highlighting the Urartians' exceptional metalworking skills.

These artifacts are linked to the reign of King Rusa II, marking Ayanis Fortress as a significant center of bronze craftsmanship in the ancient world. Following restoration, the treasures will be displayed in a local museum, providing insight into the Urartian civilization.

In a remarkable find, scientists have uncovered prehistoric elephant bones dating back approximately 9 million years in Cankiri, Türkiye, during excavations led by professor Ayla Sevim Erol from Ankara University.

The excavation site, located at the Corakyerler Vertebrate Fossil Locality along the Cankiri-Yaprakli road, has been investigated for 27 years and revealed early ancestors of elephants, including the upper arm and foot bones of a large elephant species.

Corakyerler hosts two distinct prehistoric elephant species: the larger Konobelodon and the smaller Choerolophodon. Additionally, the team identified 43 species at the site, including early horses, giraffes, and saber-toothed cats, contributing over 4,000 fossil specimens.

Originally dated to 8 million years ago, recent discoveries have pushed the dating to as far back as 9 million years based on primitive characteristics. Professor Erol announced plans for uranium-potassium dating next year to refine the site's chronology further.

This groundbreaking discovery not only enhances our understanding of ancient elephant species but also sheds light on the diverse prehistoric ecosystem in Türkiye.

During excavations in 2024, archaeologists unearthed a remarkable 64,000-year-old workshop in Inkaya Cave, located in Bahadirli village, Can district of Canakkale, Türkiye.

This site was continuously occupied for 24,000 years, offering crucial insights into early human life and craftsmanship.

Led by professor Ismail Ozer from Ankara University, the excavations have been ongoing since 2017, receiving “Presidential Decree Excavation” status since 2021.

The current project, supported by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, involves a team of 15.

Focusing on the cave's western section, researchers discovered various stone tools, including flakes and blades, dating from 40,000 to 64,000 years ago.

These findings indicate that early humans not only lived in the cave but also utilized it as a workshop for crafting essential tools.

Professor Ozer reported significant progress, with excavation reaching depths of 250 cm, revealing evidence of human activity dating back to 64,000 years.

The cave, covering approximately 400 square meters, is part of a broader network of 39 Paleolithic sites, highlighting its importance as a hub for ancient human activity.

The discoveries in Inkaya Cave are expected to enhance our understanding of human and migration patterns, with future digs promising even more groundbreaking results.

A remarkable archaeological discovery has been made at Ayasuluk Hill and the St. John Monument in Selcuk, Izmir, Türkiye, where a Roman gladiator tomb dating back to the third century B.C. was uncovered.

The excavation, led by Associate Professor Sinan Mimaroglu, revealed the remains of twelve individuals within the tomb, which was later reused in the fifth century A.D.

The tomb, associated with a gladiator named "Euphrates," features epigraphic inscriptions and three cross reliefs added during its later use.

This site has also revealed a water channel, drainage system, mosaics, and other tombs just 20 centimeters beneath the surface. Mimaroglu noted the significance of the associated church, which transformed from a small burial structure to a basilica and then a domed church during Emperor Iustinian I's reign.

Initial findings suggest the crosses inside the tomb were carved in the 5th century, with further alterations occurring in later centuries.

The tomb's construction quality exceeds that of similar finds in Istanbul, Marmara Island, and Syria. Additionally, the site provides evidence of early Ephesus dating back to the second millennium B.C.

Overall, this discovery offers valuable insights into the burial practices of the time and enhances the understanding of early Ephesus and its historical context.

The excavation of the Roman gladiator tomb in Izmir marks a significant contribution to the archaeological understanding of burial customs and historical developments in early Ephesus.

Recent excavations in Kayalipinar, a historic Hittite city in Türkiye's Sivas province, have unearthed more than 50 royal seals belonging to princes, chief scribes, and temple lords. This groundbreaking discovery, led by Associate Professor Cigdem Maner of Koc University, offers new insights into Hittite royal lineage and governance, reshaping the historical understanding of this ancient empire.

One of the most significant aspects of the findings is the discovery of seals belonging to high-ranking officials, including a prince named HattusaRuntiya, whose name translates to "Protector of Hattusa," the Hittite capital.

These seals provide crucial data about the city's connection to royal family members, revealing a deeper understanding of the Hittite administration.

As professor Hasan Peker of Istanbul University said: "These seals do more than verify the existence of historical figures; they are key to decoding the empire's administrative systems."

Kayalipinar, formerly known as Samuha, was likely the capital of the "Upper Country," a key administrative region of the Hittite Empire.

The findings suggest the city's importance stretched back to the 13th century B.C. under King Hattusili III, with connections to his nephew, son, and grandson.

These discoveries underscore the continuous occupation of the area from the Paleolithic Age through the Seljuk period, making Kayalipinar a vital archaeological site.

In a way, these discoveries echo the words of historian Howard Carter, who once said of ancient Egypt: “We are faced with a civilization with no sign of decay and no end of secrets to reveal."

The same can be said for the Hittite Empire, whose secrets continue to emerge, offering fresh perspectives on ancient history.

Recent excavations at the Kizlan Ottoman Shipwreck off the coast of Datca, Muğla, have unveiled significant artifacts shedding light on the Ottoman Empire's maritime history.

Among the discoveries are 14 rifles believed to have belonged to Janissaries, approximately 2,500 lead musket balls, and exploded cannonballs, indicating the ship was likely involved in a battle before sinking.

Notably, a remarkable set of blue-painted porcelain bowls, presumed to be produced in China for Islamic markets, was found, suggesting they may have been intended as diplomatic gifts. Personal items, including pipes, boxwood combs, copper vessels, and ceramic jugs, were also discovered, hinting at the ship's crew and soldiers.

Additionally, wood fragments from the ship’s starboard side have provided insights into Ottoman shipbuilding techniques, suggesting the ship sank in the latter half of the 17th century.

The Kizlan wreck is expected to be fully excavated by 2025, offering new perspectives on Ottoman naval history and its maritime capabilities during this period.

A monumental discovery has been made in Elazig, Türkiye, where a stunning 84-square-meter mosaic from the Late Roman and Early Byzantine periods was unearthed by local farmer Mehmet Emin Sualp while digging to plant saplings.

The find was reported to the Elazig Museum Directorate, leading to investigations that confirmed its historical significance.

This remarkable mosaic is distinguished not only by its impressive size but also by its artistic detail, depicting various animals and plants, such as lions, mountain goats, ducks, and trees, adorned with unique borders and geometric patterns.

Elazig Governor Numan Hatipoglu noted that this find showcases the vibrant local wildlife and flora of the region during ancient times.

Collaborating with the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, excavation efforts have revealed additional structures, including a church and a wine cellar, suggesting a rich archaeological site in Salkaya village, just 14 kilometers from Elazig city center.

Governor Hatipoglu emphasized the discovery's potential to lead to more artifacts and boost local archaeological exhibitions.

Mehmet Emin Sualp, who purchased the land for ₺120,000 ($3,500) in 2020, expressed his astonishment at the find's value, stating, "It’s impossible to assign a monetary value to this discovery now."

He highlighted the importance of preserving such archaeological treasures.

Archaeobotanical research at Yumuktepe Hoyuk, one of Türkiye's oldest settlements in Mersin, has uncovered two ancient wheat varieties dating back 9,000 years. The excavation, which began in 1937, has revealed layers of civilization from the Neolithic to the Medieval period.

Led by associate professor Burhan Ulas from Inonu University, the team identified Triticum timopheevii (new type spa wheat) and Triticum spelta (primitive bread wheat) through ancient DNA analysis.

Ulas emphasized Yumuktepe's significance in spreading Neolithic agriculture from the Eastern Mediterranean to Europe via land and sea routes.

The research, part of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s “Heritage for the Future” project, focuses on carbonized plant remains, shedding light on agricultural practices during the Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Byzantine periods.

Notably, these discoveries suggest that Triticum spelta was cultivated 3,000 to 4,000 years earlier than previously believed, challenging assumptions about the origins of Neolithic agriculture and highlighting Yumuktepe's crucial role in the evolution of farming in Europe.

Archaeological excavations in Sefertepe, located in Türkiye's Sanliurfa, have uncovered two significant decorative items dating back approximately 10,000 years.

These artifacts, part of the "Tas Tepeler (Stone Hills) Project" under the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, feature a leopard and a vulture alongside a human figure.

Led by associate professor Emre Guldogan from Istanbul University, the excavations, which began in 2021, highlight the cultural connections between Sefertepe and other regional settlements.

Guldogan emphasized that these items represent more than just decorative objects; they signify important cultural links to ancient communities.

This year's discoveries include unique jewelry made of jade, believed to have originated from outside the local area, potentially from regions like Israel and Palestine.

Guldogan noted that these pieces reflect the ornamental practices of ancient peoples, akin to modern jewelry use, and showcase their aesthetic and cultural significance.

While discussing the materials, Guldogan emphasized the need for additional research to trace the origins and cultural significance of the artifacts. He noted that similar materials have been discovered in southern regions, highlighting the potential for deeper connections between these findings and broader historical contexts.

The discoveries in Sefertepe not only illuminate the cultural practices of early Neolithic societies in Türkiye but also underscore the region's ties to other ancient civilizations.

As research progresses, these findings are expected to provide deeper insights into the symbolic significance of these artifacts and the trade networks that existed 10,000 years ago.

The archaeological discoveries in Türkiye during September 2024 underscore the country's rich and diverse historical tapestry, revealing significant insights into various ancient civilizations, from the Hittites and Medes to the Romans and Ottomans. Each finding –from the enigmatic Byzantine protective tablet at Silifke Castle to the remarkable 64,000-year-old workshop in Inkaya Cave – illuminates the intricate cultural practices, religious beliefs, and societal structures of the past.

These artifacts not only enhance our understanding of ancient life in Anatolia but also highlight Türkiye’s pivotal role as a crossroads of civilizations.

As archaeologists continue their excavations, they unlock the secrets of the past, allowing us to appreciate the profound legacy that these discoveries represent.

The ongoing commitment to uncovering and preserving Türkiye's archaeological treasures ensures that future generations will remain connected to the rich history that shapes the region today.