EU leaders back von der Leyen for another term as commission chief

Following a late-night agreement, European Union officials appointed former Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Costa to head the European Council and filled the bloc’s top institutional jobs for the next five years.

All three nominees come from the centrist alliance dominating the EU parliament following recent elections. This is despite gains by the far-right, including Italy’s Giorgia Meloni, who publicly resisted the top jobs deal.

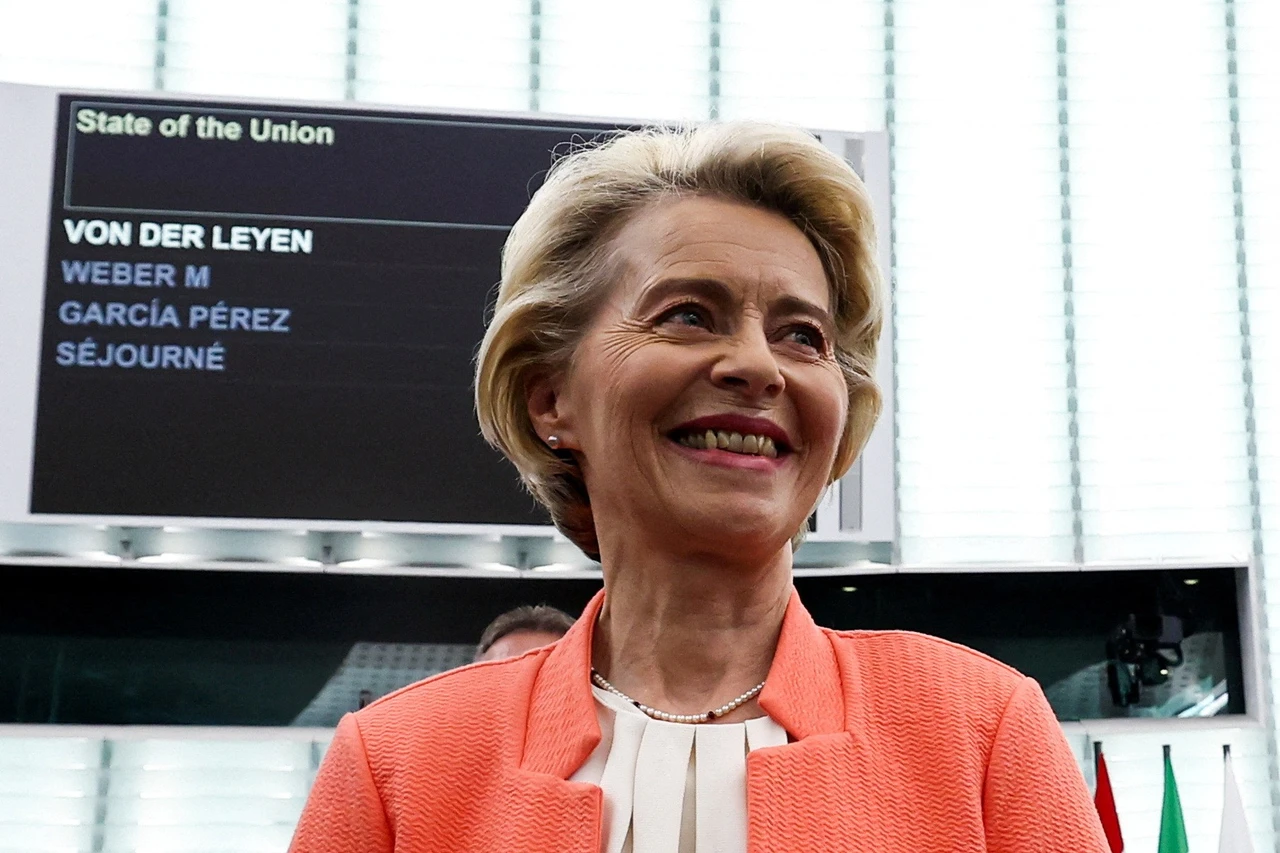

Costa, 62, will automatically succeed Council President Charles Michel this year. However, both Ursula von der Leyen, 65, and Kaja Kallas, 47, need to secure majority support in the European Parliament, starting with a July vote on the commission chief, which is expected to be close.

During her first term, von der Leyen, a former German defense minister, was tested by multiple crises, from the COVID-19 pandemic to the Ukraine war. If confirmed for a second term, she will face significant challenges, including the Russian threat, climate change, and a rising China.

Von der Leyen expressed her “gratitude” to the leaders in Brussels for backing her second term, promising to outline her political priorities soon to win the confidence of parliament.

Costa, addressing the press via videolink, declared his commitment to promoting unity among member states. He stated, “Europe and the world are facing challenging moments, but the European Union has demonstrated its resilience in the past.”

Kallas emphasized the “enormous responsibility” she has been given amid acute geopolitical tensions. “There’s war in Europe, but there’s also growing instability globally. These are the main challenges for European foreign policy,” she said.

The final lineup was largely expected, as an inner group of leaders had agreed on a draft deal days earlier. This was a stark contrast to the drama of 2019, when von der Leyen emerged from a backroom deal.

The agreement divides posts among von der Leyen’s center-right European People’s Party (EPP), Costa’s Socialists and Democrats (S&D), and Kallas’s centrist Renew Europe. Lawmakers are also expected to return the EPP’s Roberta Metsola as EU Parliament president.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz praised the “quick, forward-looking” decisions, stating the nominees would “ensure that Europe is well-positioned in challenging times in the coming years.”

Contentious process

With France heading to the polls on Sunday for the first round of an election where the far-right National Rally has a chance of leading the government, there was eagerness to finalize the EU jobs.

Despite the centrists’ strength, diplomats said there was little appetite for forcing through a deal without consensus. Hungary’s nationalist leader Viktor Orban denounced the process as a “stitch-up,” claiming, “European voters have been deceived.” However, his opposition was not enough to derail the accord, which needed support from 15 out of 27 leaders.

Leaders were more concerned about securing buy-in from Italy’s Meloni, who called the deal-making process “surreal” and accused fellow leaders of acting like “oligarchs.” She argued that the election success of her hard-right European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group, set to be the EU Parliament’s third-largest force, and Italy’s status as the bloc’s third-biggest economy should be reflected in the EU leadership.

Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk, who negotiated the deal for the EPP, signaled early in the day that Italy’s role was crucial. “There is no Europe without Italy, and there’s no decision without Prime Minister Meloni,” he told reporters, with similar sentiments echoed by leaders from Greece, Cyprus, and Austria.

Though Meloni did not secure a seat at the top table, she made it clear she wanted an influential role for Italy, starting with a vice presidency in the next European Commission with influence over industry and agriculture.

In the end, Meloni abstained from voting for the commission chief and voted against both Costa and Kallas, according to diplomats. She posted on social media afterward, criticizing the deal as “wrong in method and substance” and vowed to “continue to work to finally give Italy the weight it deserves in Europe.”