Headscarf, secularism, and identity: What’s happening in Turkish Cyprus?

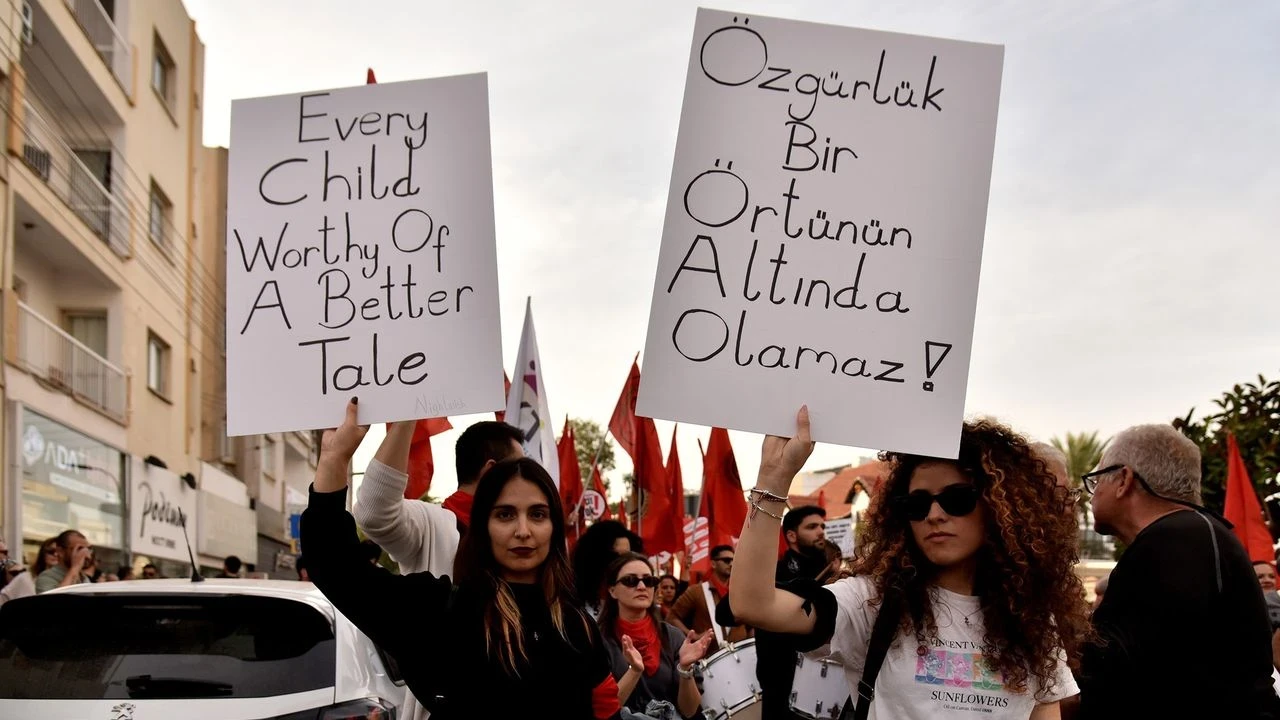

A protester in a crowd holds a banner reading "No Passage to Bigotry" during demonstrations in Lefkosa, April 9, 2025. (Photo credit: Independent Turkish)

A protester in a crowd holds a banner reading "No Passage to Bigotry" during demonstrations in Lefkosa, April 9, 2025. (Photo credit: Independent Turkish)

On April 12, the Ministry of Education in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) introduced a revised dress code regulation, informally dubbed the “Headscarf Regulation,” allowing students in middle and high schools to wear headscarves. The amendment officially permits students to wear clothing that aligns with their religious beliefs, provided it does not conceal or replace the designated school uniform.

TRNC Prime Minister Unal Ustel defended the move, emphasizing that the regulation is rooted in universal human rights principles and protects religious freedoms. He described the decision as one that upholds individual liberties and enables students to dress according to their faith.

Now the streets of the republic’s capital have become a stage for this ideological tug-of-war, with protests and counter-protests unfolding in close succession.

Echoes of the traumatic past in Türkiye

Those familiar with the issue, especially within Turkish society, will recognize that this is part of a much deeper collective trauma. The 1990s, particularly during the period known as the Feb. 28 Process, were marked by heightened tensions over religious expression, with headscarf-related discrimination reaching its peak. Although the military did not directly govern, it exerted a significant influence over politics for decades. Military influence in Türkiye created undue pressure on Türkiye’s conservative majority.

Following the 1997 National Security Council meeting—widely seen as orchestrated by the military under the pretext of combating “religious reactionism”—a series of measures were adopted. University rectors and members of the judiciary were briefed and effectively instructed to prevent headscarved students from entering university campuses. These directives institutionalized a strict secular stance, reinforcing barriers for women who chose to wear the headscarf in public education and professional life.

The following year, a headscarf-wearing member of parliament was expelled from the national assembly solely because of her attire. It wasn’t until the period between 2007 and 2013 that such restrictions began to ease, following a series of legislative reforms driven by the ruling AK Party and supported by the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP).

More recently, the conversation in Turkish Cyprus reignited after a widely circulated video on social media showed a student being publicly reprimanded and denied entry to school because of her headscarf. The footage, which sparked public outrage, served as a stark reminder of past discriminatory practices and reawakened deep societal memories around the issue of religious visibility in schools.

Origins of controversy

The recent debate of Turkish Cyprus traces back to an incident in March at Irsen Kucuk Middle School in Lefkosa, where a student attempted to attend class wearing a headscarf. Teachers objected, citing the existing dress code regulations, and responded with a protest of their own.

In response, the Council of Ministers moved to amend the existing disciplinary regulation to accommodate religious dress in schools. While the initial regulation was withdrawn amid criticism from teachers’ unions and opposition parties, a revised version was quickly reintroduced. This updated regulation, which reaffirms students’ rights to wear headscarves on religious grounds, was published in the Official Gazette and has since come into force.

Revolution of tears: A student’s story

Beyond legal and political dimensions, the story of a single student became emblematic of the wider societal tensions surrounding the discussion of identity and the state. According to the father of Ikra Simsek, whose daughter chose to wear the headscarf after her study and reflection, the family fully respected and supported her decision. Initially, she was allowed to attend school. However, she soon faced warnings and pressure and was eventually denied entry altogether.

Despite her brave stance in public, according to her father, she suffered from crying for many days due to the treatment she received in school. Her story of struggle gained public attention only after a video emerged showing her confronting teachers from the same union that had objected to her attire. The video quickly went viral on Turkish social media, sparking widespread debate.

While legal experts have pointed out that preventing a student from entering class or taking an exam constitutes a violation of basic rights, similar forms of pressure were previously justified under the principle of secularism in Türkiye.

Protests erupt in capital over secular concerns

The policy change has triggered significant backlash, culminating in widespread protests on Tuesday in the capital, Lefkosa. The demonstrations drew the participation of trade unions, civil society organizations, and political parties, with crowds chanting slogans such as “No Passage” and “Cyprus is secular and will remain secular.”

Among the demonstrators were Mehmet Kucukk and Serdar Denktas, sons of TRNC founding leaders Dr. Fazil Kucuk and Rauf Denktas, signaling broader political resonance and generational concerns regarding the policy shift.

Clothing elements must be used in a simple manner that does not obscure the student’s face, identity, or communication ability. The use of attire that completely covers the face (such as burqa, niqab, or veil) is not permitted in educational settings.

New circular of the Ministry of Education

Protests and counter-protests

Opponents of the regulation argue that labeling students with religious symbols “before their identity development is complete” is problematic. They warn that the new policy risks compromising secular values in the public education system.

One participant of this week’s protests described the move to accommodate observant students as an extension of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s policies toward Turkish Cyprus, suggesting that the headscarf regulation reflects broader ideological influence from Ankara.

Notably, the TRNC already hosts the Hala Sultan College, a religious school that offers theological education, demonstrating that faith-based education options are present within the existing system.

To better understand how the issue is perceived socially, it’s worth looking across the island to the Greek Cypriot-administered south. In contrast to the recent controversy on the north side, headscarves are permitted in public without restriction in the southern Greek region.

Organized in response to the earlier protests, a gathering was called by Erhan Arıklı, the leader of the Rebirth Party (YDP). Branded as a “Respect for the Homeland” rally, the event served as both a show of support for the headscarf regulation and a symbolic gesture of solidarity with Türkiye in front of Ankara’s embassy in Lefkosa.

Familiar debate, but with quicker response

Years ago in Türkiye, even the terminology used during debates over head coverings was enough to reveal where someone stood. Supporters of the regulation often referred to it as “turban” (a modern-style headscarf), while opponents labeled it the “basortusu issue” (the traditional headscarf problem). The choice of words wasn’t just semantic—it was political.

Now, Turkish Cyprus appears to be undergoing a similar phase. However, this time, the experience of Türkiye’s past seems to be informing quicker, more structured responses.