Finnish Tatars preserve centuries-old Turkic heritage in heart of Scandinavia

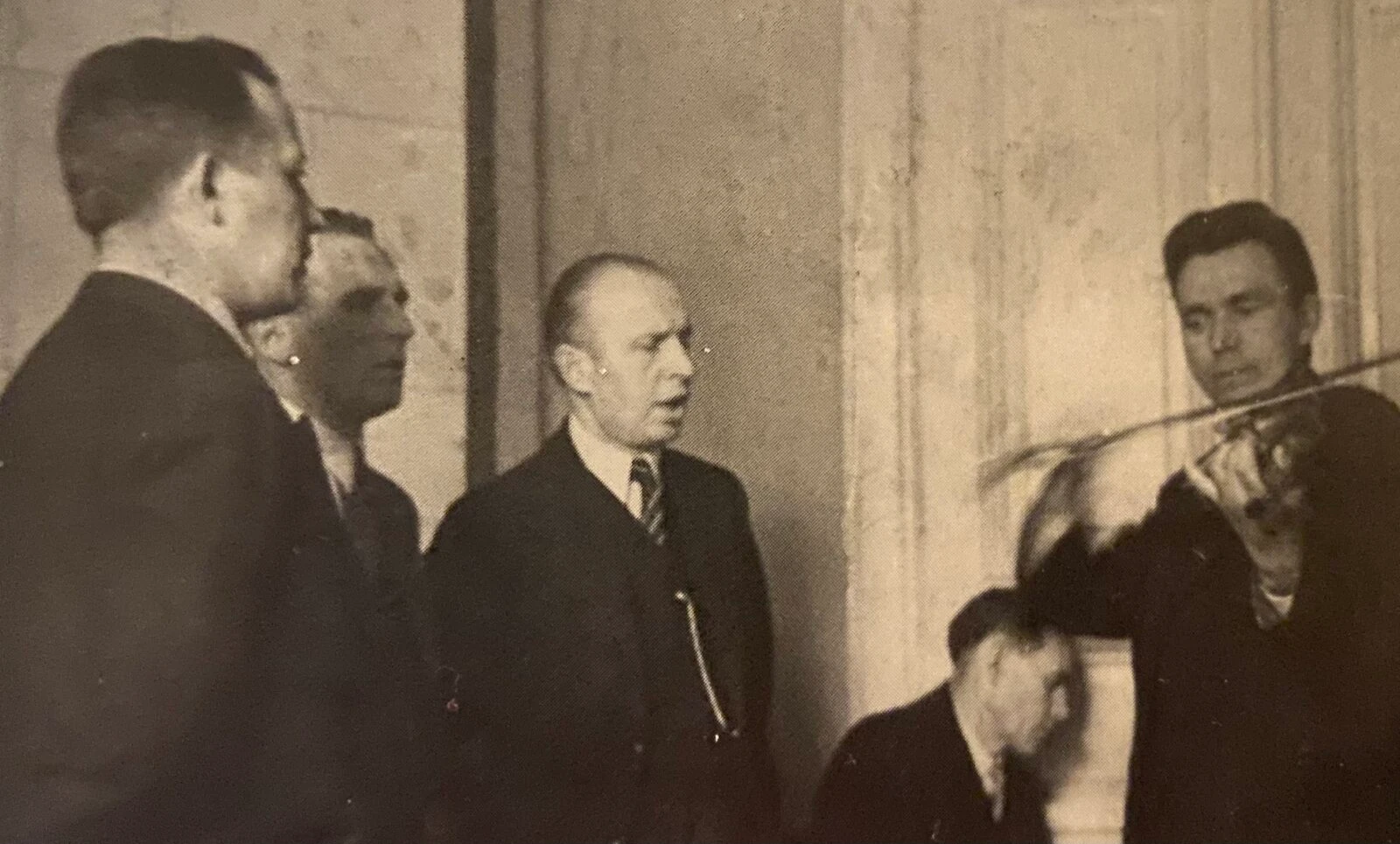

Finnish Tatars celebrating the 10-year anniversary of Türkiye in the festive hall of VPK in Tampere, behind, flags of Türkiye and Finland and pictures of presidents of both countries, October, 1933. (Photo via Finnish Heritage Agency)

Finnish Tatars celebrating the 10-year anniversary of Türkiye in the festive hall of VPK in Tampere, behind, flags of Türkiye and Finland and pictures of presidents of both countries, October, 1933. (Photo via Finnish Heritage Agency)

The Finnish Tatars (Suomen tataarit), a Turkic-speaking Muslim minority, have played a quiet but powerful role in shaping Finland’s multicultural landscape for over a century.

With roots in the Volga-Ural region of the former Russian Empire, this community of just 600–700 people has managed to preserve its cultural identity despite wars, migration, and the pressures of assimilation.

Arriving primarily between the late 1800s and early 1900s, Finnish Tatars are descended from Mishar Tatars — a subgroup of Volga Tatars — who originally came as merchants from the Nizhny Novgorod region. Drawn by the economic potential of Finland, then part of the Russian Empire, these traders began settling permanently after discovering friendlier business conditions and a receptive society.

Finland’s first Muslim community

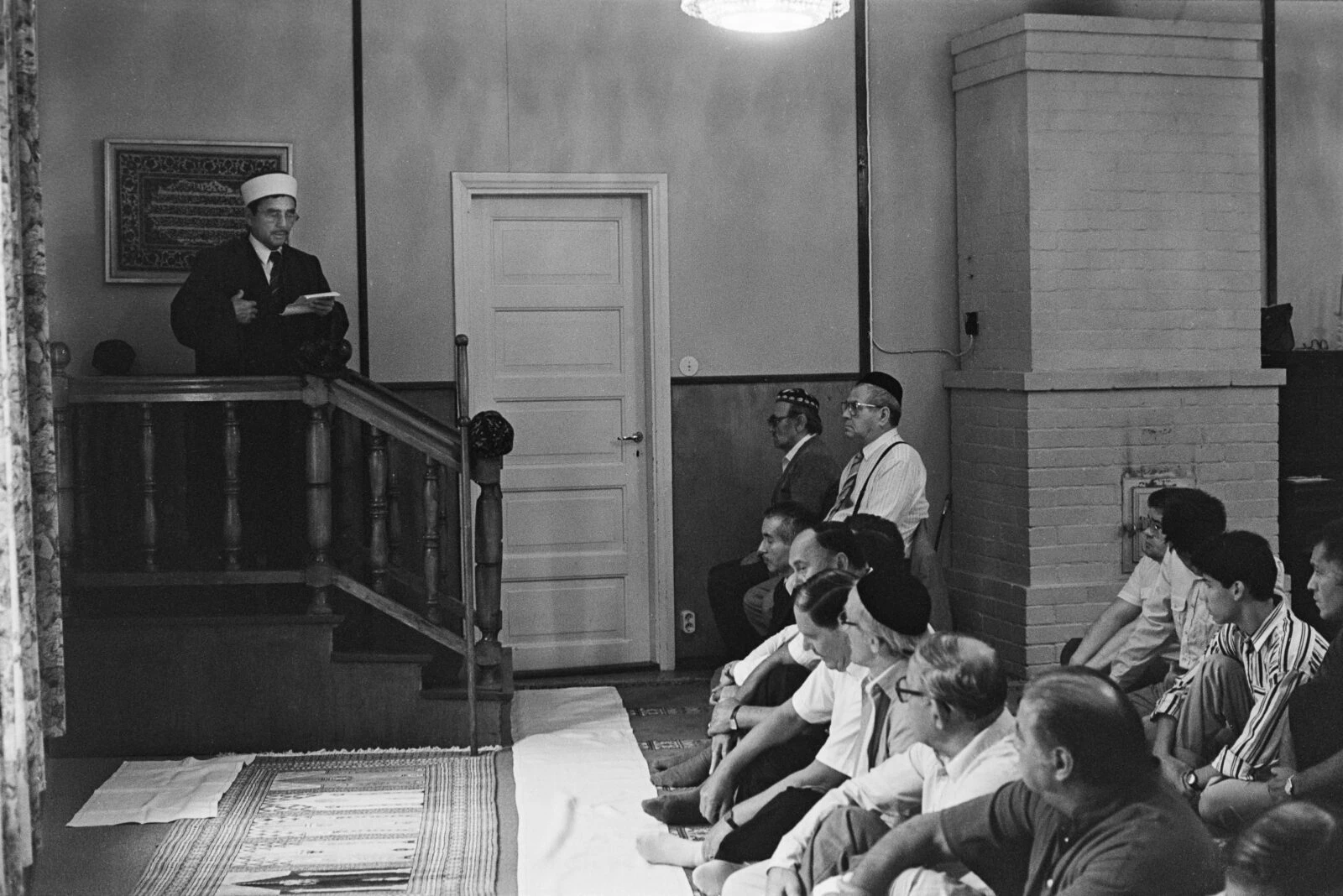

Though small in number, the Finnish Tatars are Finland’s oldest Muslim community. They established their first congregation in Helsinki and went on to form cultural associations in cities like Turku and Tampere. Their arrival predates larger waves of Muslim immigration by decades.

Some historians trace Muslim presence in Finland even further back. During the Great Northern War and Russo-Swedish conflicts of the 18th century, Turkic-speaking soldiers — possibly Tatars or Bashkirs — served in military units on Finnish soil. In the 19th century, mullahs such as Izzatulla Timergali played key religious roles, laying the foundation for Finland’s Muslim heritage.

Finnish Tatars’ cultural continuity and transformation

In their early years in Finland, Tatars were primarily seen as Muslims. However, after the establishment of the Republic of Türkiye in 1923, many began identifying themselves as “Turks,” inspired by Ataturk’s reforms and shared linguistic roots. They adopted the Latin alphabet, replacing Arabic script, and named their associations “Turkish” rather than “Tatar.”

By the 1970s, a resurgence of interest in their Tatar roots began, especially following renewed connections with Tatarstan. The shift became official in 1974, when a “Day of Tatar Culture” was publicly held in Jarvenpaa, marking the community’s reassertion of its distinct identity.

Today, Finnish Tatars proudly embrace the ethnonym “Tatar” while maintaining ties with both Türkiye and Tatarstan. In 2024, a history of the Finnish Tatars written by Dr. Ramil Belyayev, the congregation’s imam, was translated into Turkish and published in Ankara — a powerful symbol of their enduring cultural links.

Wartime service and sacrifice

The Finnish Tatar community has also contributed to the country’s defense. During the Winter War and Continuation War, 156 Tatars served in the Finnish armed forces. Ten died in combat, while many others were wounded.

Tatar women joined the Lotta Svard organization, offering crucial support during wartime. In 1987, their sacrifice was honored with a memorial plaque placed in the main congregation building in Helsinki.

Türkiye and Tatarstan: Dual connections

Finnish Tatars maintain strong cultural and diplomatic ties with both Türkiye and Tatarstan. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan visited the community, expressing admiration for their ability to preserve traditions in a distant land. Former president Abdullah Gul also paid a visit, as have various Turkish officials over the years.

Meanwhile, Tatarstan’s leader, Rustam Minnikhanov, has made efforts to strengthen the bond between Kazan and the Finnish diaspora. Visits from both sides have revitalized connections with ancestral villages and bolstered cultural exchange.

In 2005, Turkish broadcaster TRT filmed a documentary on the Finnish Tatars, bringing their story to a wider audience across the Turkic world.

A legacy of resilience

Despite their small size, the Finnish Tatar community has carved out a meaningful space in Finnish society. Through language education, cultural associations, and the preservation of religious life, they continue to uphold a unique identity that links the Volga, Anatolia, and the Nordic north.