What Europe owes to the Islamic world of science

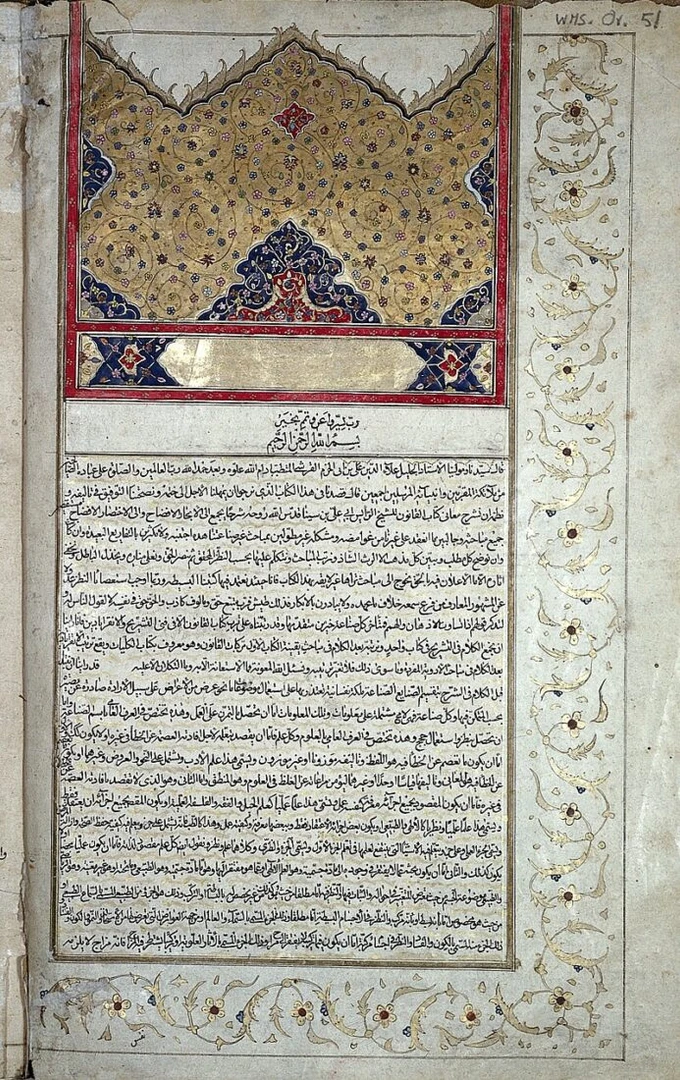

Islamic Science and Technology Museum which showcases a display of Islamic accomplishments in the sciences in Istanbul, Türkiye. (Photo courtesy of Ministry of Culture and Tourism)

Islamic Science and Technology Museum which showcases a display of Islamic accomplishments in the sciences in Istanbul, Türkiye. (Photo courtesy of Ministry of Culture and Tourism)

The story of Europe’s scientific development is usually told in a way that feels incomplete. The common version jumps from Ancient Greece to the European Renaissance, as if little else happened in between. But history shows a different picture—one where Muslim scholars played a central role in preserving, developing, and passing on scientific knowledge.

Between the 9th and 13th centuries, the Islamic world was home to major advances in science, philosophy, and medicine. Scholars working in Arabic across cities like Baghdad, Cairo, Bukhara, and later Istanbul studied earlier Greek works, but more importantly, they made their own discoveries. Their writings were later translated into Latin and reached European universities, where they influenced generations of thinkers.

At the time, Arabic was the language of science. Texts written in Arabic circulated widely and were treated with authority in Europe. Cities such as Toledo and Palermo became centers of translation and exchange. Istanbul and Sarajevo later joined this network as important cultural and intellectual bridges. The flow of knowledge between East and West was real and active. Yet, over time, the names of many Muslim thinkers were quietly removed from the story.

Knowledge taken, credit withheld

Learning from others has always been part of science. But in the case of Europe’s early modern scholars, many borrowed heavily from Arabic works without giving credit. This silence in the historical record is one of the reasons so many important Muslim contributions remain unknown to the wider public today.

William Harvey, the English physician often credited with discovering blood circulation, is one example. His work in the 17th century is praised as groundbreaking. But in reality, Ibn al-Nafis, a Syrian doctor writing more than 300 years earlier, had already described pulmonary circulation in clear terms. His work was copied and known, yet it was not mentioned when the idea was later published in Europe.

Isaac Newton is another case. His three laws of motion are still taught today. But ideas very similar to his appear in much earlier Islamic texts. Avicenna (Ibn Sina) wrote about motion and rest in a way that mirrors Newton’s first law. Fakhr al-Din al-Razi discussed force and balance in terms that closely match Newton’s second and third laws. Some of these Arabic texts even had Latin or English notes written in the margins, showing that European scholars had access to them.

In philosophy, the pattern continues. Descartes, one of the founding figures of modern Western thought, raised questions about the nature of reality and doubt. These same themes had been explored in depth by Imam al-Ghazali centuries earlier. When Egyptian scholar Dr. Mahmoud Zakzouk attempted to research the connection between the two, he reportedly faced resistance in Europe. This kind of pushback shows that some parts of history remain difficult for institutions to confront.

Turkic thinkers and shared heritage

The contributions of Turkic Muslim scholars, or we might say of the heritage of today’s Turkish people, are also part of this story. Their work helped shape the scientific tradition across the Islamic world and beyond.

Ali Kuscu, a mathematician and astronomer from Samarkand, later served in the Ottoman court. He studied under Ulugh Beg and played a key role in introducing Central Asian astronomy and mathematical knowledge to Istanbul. There, he helped develop science education and left a lasting mark on Ottoman scholarship.

Mahmud al-Kashgari, writing in the 11th century, focused on language. His Compendium of the Turkic Dialects is a valuable record of Turkic culture, filled with expressions, proverbs, and stories. It shows that scientific and scholarly work also includes preserving identity, language, and social knowledge.

Al-Biruni, one of the most respected thinkers of the Islamic world, came from Central Asia and worked in a Turkic cultural environment. He studied astronomy, geography, and natural science. His estimates of the Earth’s circumference were remarkably close to modern measurements. He used careful observation and comparison long before the scientific method was formally defined in Europe.

These scholars were part of a wider intellectual world. From Bukhara to Baghdad, from Cairo to Istanbul, and westward through Sarajevo, knowledge traveled through books, scholars, and institutions. It eventually reached Europe. But in many cases, the names of those who carried it most of the way were left behind.

Why it still matters today

This is not about national pride or rewriting history. It is about fairness. Europe’s scientific success was real, but it was not achieved alone. Many of the ideas that shaped the modern world were built on earlier work done in Arabic by Muslim thinkers, including many from Turkic backgrounds.

Türkiye, with its deep connection to both Islamic and Turkic traditions, can help bring this fuller story to light. But it must do so with solid research, patience, and care. The aim should not be to replace one version of history with another; it should be to tell the complete version.

Including figures like Ibn al-Nafis, Ali Kuscu, Al-Biruni, and Mahmud al-Kashgari does not take away from the achievements of Newton or Descartes. It simply reminds us that knowledge is a shared journey, built across cultures and generations.

There is also an ethical issue that should not be ignored. Muslim scholars who studied Greek knowledge almost always named their sources. They commented on them, challenged them, and added to them. They treated knowledge as something to develop and pass on, not something to hide or claim as their own.

Some European scientists, on the other hand, translated Arabic texts and then published the contents under their own names, without giving any credit. British writer Peter Watson, in his book History of Ideas, notes that hundreds of Arabic works were reused this way. For a tradition that values academic honesty, this should be remembered as a serious failure.

This is not a small footnote; it is a matter of integrity. If science is meant to serve all people, then its history should include all people. Giving credit where it is due is not only fair, it is long overdue.

About the author: Ceren Harputlu is an analyst specializing in international relations. She occasionally contributes as a freelance writer.