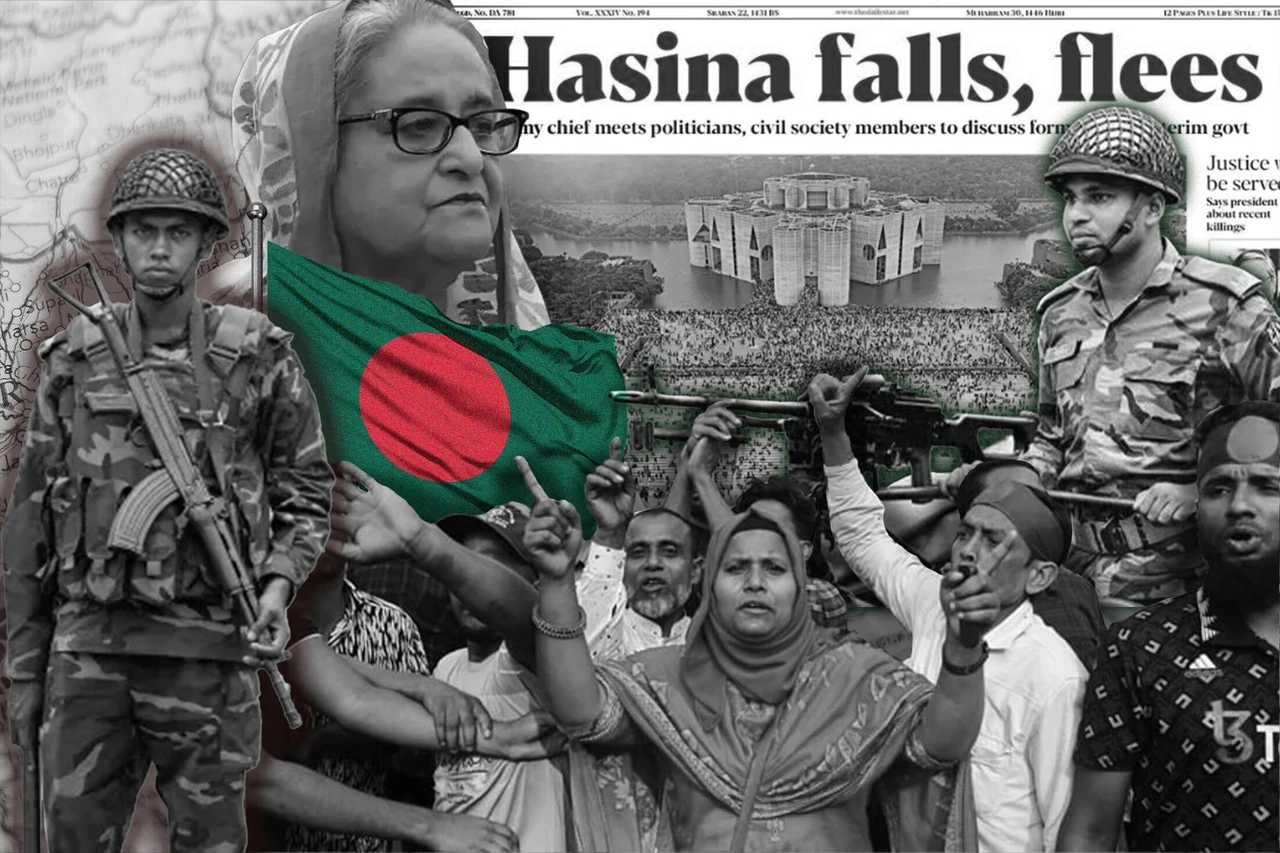

Ousted South Asia’s longest-ruling autocrat, what’s next Bangladesh?

The pivotal student protests, widely seen as the final nail in the coffin of Bangladesh’s political repression, started in early July. (Photo by news staff)

The pivotal student protests, widely seen as the final nail in the coffin of Bangladesh’s political repression, started in early July. (Photo by news staff)

History was charted anew in Bangladesh when a student protest over the public quota system morphed into a massive movement ousting South Asia’s longest-ruling autocrat Hasina Wajid – who held the reins of the country for 19 years in multiple terms.

While some celebrated the victory, others anxiously sought answers about the future of a nation grappling with the angst and frustration of Gen-Z after a transformative movement that, unfortunately, lacks solid leadership.

Final nail in coffin?

The pivotal student protests, widely seen as the final nail in the coffin of Bangladesh’s political repression, started in early July when students from various universities across the country began voicing their opposition to the public quota system.

Under Bangladesh’s quota system, 56% of government positions were reserved for specific groups, including 30% for descendants of the 1971 War of Independence freedom fighters, leaving just 44% of merit-based spots for the public.

Following the deadly historic protests leading to over 1,000 deaths reported unofficially, the Bangladeshi Supreme Court ordered the slashing of the government quota to 5% with 93% of jobs allocated for merit.

Original System

Reformed System

However, it was too late to quell the student protests that had already challenged the autocratic rule in Bangladesh. The fight had evolved beyond the biased quota system; it now encompassed demands for road safety, skyrocketing educational costs, and the overall lack of opportunities for the country’s youth.

Above all, it demanded severe consequences for those responsible for the deaths of over 300 students.

Students, not criminals

The Hasina-led regime had claimed these students were criminals planted by the opposition to instigate riots. Internet blackouts, tear gas shelling, enforced curfews and unwarranted arrests couldn’t dampen the spirits of protesting students. Their uprising, now recognized globally as a liberation movement, continued unabated.

Finally, the sun dawned upon Dhaka on Aug. 5 with Wajid’s unprecedented resignation following days of mass protests and political turmoil in the country. The ousted premier, accompanied by her sister, fled the country in a military transport aircraft C 130J headed to London where she reportedly sought exile.

Meanwhile, Bangladesh army chief Waker-uz-Zaman announced the prime minister’s resignation in a press conference, suggesting the country would now work to form an interim government.

But an interim government led by who?

Student protest leaders have called for the interim government to be led by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus, a prominent critic of the ousted premier.

The Bangladeshi military has appeared to support this demand. Yunus, the “banker of the poorest of the poor,” is an economist and banker who founded Grameen Bank in 1983 to provide small loans to entrepreneurs who typically wouldn’t qualify for traditional financing. His micro-credit concept earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006.

But is Yunus the answer to Dhaka’s mounting problems? Does he offer the leadership needed to steer Bangladesh’s struggling ship through turbulent waters?

Economic challenges, political diplomacy together

Yunus holds a distinguished track record in poverty alleviation and social entrepreneurship, perfectly complemented by his expertise in sustainable development. However, these strengths may not suffice for leading a country like Bangladesh, which has a complex and volatile political landscape.

The country with the world’s fourth-largest population currently needs a leader who can adeptly navigate not only economic challenges but also the intricacies of governance, diplomacy and internal politics.

Although Yunus’s leadership of the interim government could attract global support and foreign investments because of his international stature, his political experience is limited. This could be a daunting challenge for the noble laureate. Setbacks like corruption, infrastructure development and law and order need a more comprehensive approach, which may extend beyond Yunus’s area of expertise.

Having said that, Yunus has been a prominent advocate for wider social impact over profit numbers and temporary gains – an approach that might upset a lot of stakeholders.

Above all, bringing all political leaders on one page might be a strenuous task for Yunus as he is a polarizing figure within Bangladesh. His political involvement has often been met with resistance from certain political figures. This polarization might be one of the biggest hurdles in his way to implement reforms to address the needs of many Bangladeshis who are underserved by traditional economic systems.

Yunus’ aptitude in social development and micro-financing might be an asset for Bangladesh but the country also needs traditional political leadership and statecraft given the economic pressures and political instability.

Beginning of Arab Spring?

The country needs a team that has a track record of managing diverse issues and navigating complex political environments and is capable of crafting inclusive policies, implementing institutional reforms, and fostering international collaboration.

Besides, engaging diverse stakeholders such as the civil society, the private sector and international partners, the country can pursue economic and social reforms that address both immediate challenges and long-term development goals.

With the world viewing Wajid’s resignation as the end of South Asia’s longest autocratic rule, could this mark the beginning of a South Asian version of the “Arab Spring” under Yunus’ leadership?

While the Arab Spring still seems a far-fetched approach, the new leadership will certainly alter the political map of South Asia, a region that has a profound impact on global security, trade and environmental issues.