Fleeing Austrian and Russian oppression, Polish refugees modernized the Ottoman Army

"Scene with the Sultan" by Polish painter Stanislaw von Chlebowski. (National Museum in Krakow, Poland).

"Scene with the Sultan" by Polish painter Stanislaw von Chlebowski. (National Museum in Krakow, Poland).

Six hundred and eleven years ago, Poland was among the first states that the Ottoman Empire recognized in the 15th century. Before other nations, Poland had embassies in Istanbul, and later, in the last quarter of the 15th century, a Polish mission was also established in Crimea.

Since the Crimean Khanate was one of its autonomous principalities, the Crimean Khanate had an embassy in Krakow, while Poland maintained an embassy in Bakhchisaray. These relationships complemented each other, especially with the presence of a prominent ambassador in Istanbul. These relations continued until Poland ceased to exist, after which the Turkish Empire unofficially harbored some Polish representatives, such as the national committee after 1830. Poland regained its independence after 1918.

In the 15th century, Poland was one of Europe’s major powers. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth inevitably clashed with the Ottomans, who had become a Balkan empire by the early 15th century and were advancing into Central Europe. Over the centuries, these two powers not only met on battlefields like Varna and Nicopolis but also engaged in vibrant commercial and cultural exchanges.

Material cultural elements, clothing, and even some fashion items and tools seen in daily life, as well as loanwords in both languages, are significant examples of this exchange. For instance, Bulgarian historian Tsvetana Georgieva states that trade with Poland in the Ottoman Bulgarian provinces alone reached an amount of 5 to 10 ducats of gold annually by the end of the 15th century. During this period, Jan I Albert was the King of Poland and Lithuania, while Bayezid II was the Ottoman Sultan.

Ottoman-Polish relations

Ottoman-Polish trade significantly contributed to the development of agriculture and economic life in the Balkan countries. Poland had diplomatic relations not only with the Ottoman capital but also with its vassal states like the Principality of Transylvania and the Crimean Khanate. The rising power of Muscovy and the conflicts between the Crimean Khanate and the Ottomans prompted Poland to take an early interest in the internal affairs of these states.

This interest extended to their military, cultural, and economic structures. The reports written by Polish ambassadors are valuable historical sources that shed light on the era, reflecting genuine knowledge and talent. These sources provide detailed information about the state of the Ottoman lands at that time. As an example, we can cite the “Sefaretname” (Embassy Memoir) of Martin Broniewski, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s ambassador to the Crimean Khanate. Similarly, the “Sefaretnames” written by Ottoman ambassadors sent to Poland are of particular importance for Polish history, starting from the 17th century. We should also mention Mehmet Efendi’s 1730 Polish “Sefaretname” and Mehmet Agha’s 1758 “Sefaretname.”

Ottoman ambassador Mehmet Agha arrived in Poland on February 19, 1758, and was warmly received by both the nobility and the common people of the Commonwealth. The Ottoman ambassador could not help but vividly describe the generous and warm character of the people, the nobility, and the king. A month later, when he set out for his return journey, the king gave him a thousand ducats of gold. Both of our ambassadors made very positive statements about all classes of Polish people.

In fact, even though the 17th century was a period of constant warfare between the Turks and the Poles. However, Ottoman rulers had long recognized the vital importance of Poland’s existence and strength for themselves.

Ottoman-Polish relations after the second siege of Vienna

King Jan Sobieski, who attacked from the Kahlenberg hills in 1683 during the Second Siege of Vienna, causing the siege to collapse and the Ottoman army to disintegrate, unknowingly prepared the beginning of Poland’s decline rather than a Polish victory. Because peace and power are only possible with the continued existence of both forces.

Indeed, after this event, the fate of Polish history changed. After 1683, Ottoman-Polish relations focused not only on alliance and friendship but also on vital unity against Russia and Austria. Peter the Great’s Russia emerged as a European power, which drew Poland closer to the Ottoman Empire.

The Prut campaign in 1711 was a result of this alliance policy. We know that the skilled Polish diplomat Poniatowski was present on the battlefield with the Swedish king. The 1768 Russo-Turkish War was declared by the Ottomans due to Tsarina Catherine the Great’s constant interference in Polish affairs. The famous historian Cevdet Pasha describes the situation in those years: “Tsarina Catherine constantly interfered in Polish affairs and sent her troops to Poland for the second time. Upon this, we declared war on Russia because Russia moved its troops through the Ottoman border provinces.”

After the Ottoman Empire’s defeat, Poland was partitioned for the second time. During the final partition of Poland, the Ottoman Empire was in a severe internal and financial crisis. At the time Cevdet Pasha remarked, “When this ominous news reached Istanbul, it served as a lesson for us. Therefore, the Ottomans chose to complete the necessary military and financial reforms as soon as possible.”

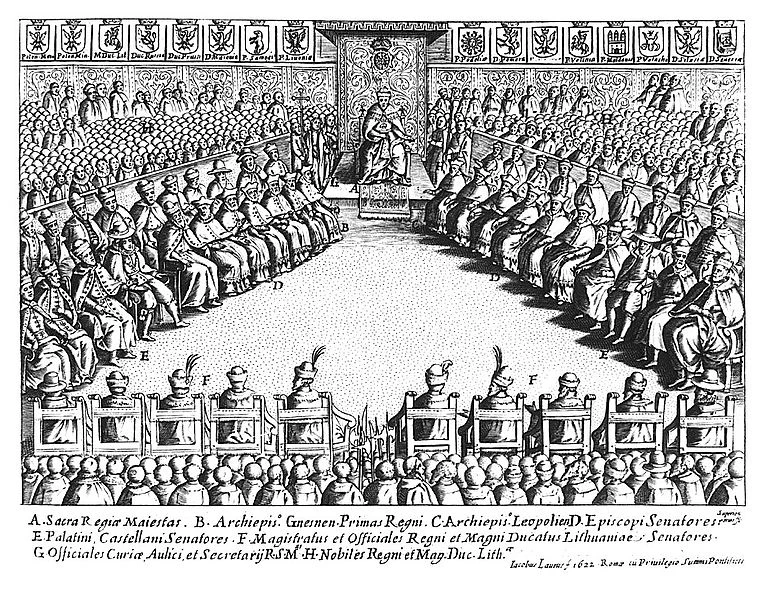

Cevdet Pasha blames the Polish constitution and administrative system for the calamity that befell Poland. This view is also seen as a weakness in Polish history in Western literature. As is known, Poland was a republic with a king at its head. Just as the Venetian Senate elected its Doge, the Polish Sejm elected the king for life. The Sejm, the Polish diet, consisted of representatives of the aristocracy.

The formation of the Sejm was very interesting, as the number of land lords in Poland was vast. Even within this group, there were mirzas who had taken refuge in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from the Crimean Khanate due to internal conflicts. These mirzas had their titles of nobility confirmed and their privileges protected because they fought on the Polish side against Russia in wars. They also maintained their Muslim faith.

However, when it came to elections, these land aristocrats, who gathered by the thousands in the Wawel Castle in Krakow, elected a small number of diets from among themselves. In this respect, it was very important for the diet’s decisions to be made unanimously and for the members to have veto power. In this structure of Poland, it can be said that as much as a weakness, a very broad democratic habit was born.

Ottoman Empire opposed the partition of Poland

Although the news of Poland’s partition reached the Ottoman capital, the state did not hesitate to recognize the newly arrived Polish ambassador on the same day and accept him into the presence of the Sultan.

However, after the ambassador appeared before the Imperial Council and the Sultan, he immediately returned to his country. The partition and disappearance of Poland was an event that the Ottoman Empire never desired and never recognized.

In the protocol of the Ottoman palace, there was always a place for the absent Polish ambassador. It is rumored that the Chief Chamberlain would call out “Polish ambassador” three times during ceremonies and then announce “he is still on his way,” reflecting the policy of that period.

Since that time, the empire of the Turks has been the last refuge for all Polish patriots who fought for Poland’s independence. The 19th century, when Poland’s struggle for freedom intensified, was also a peak period for Polish-Turkish relations. The Ottoman Empire was a refuge for Polish patriot nationalists, and these grateful people wholeheartedly participated in the modernization efforts of their second homeland, rendering important services.

If we consider the difficult situation of the Ottoman Empire in the mid-19th century, it is difficult to describe in words the courageous policy of this state in defending the lives of Polish and Hungarian refugees against Russia and Austria. The Ottoman state not only defended the rights of the refugees but also recognized the Polish National Committee, which could be considered a government-in-exile established after the 1831 Polish Uprising, and treated the committee’s representative in Istanbul almost like an ambassador.

The Sublime Porte (Istanbul) never hesitated to maintain a supportive relationship with the Polish National Committee. It is clear that the Ottomans institutionalized such national independence formations that they supported, harboring and controlling their members. In particular, a Polish National Committee also operated in Istanbul after the uprising. The implicit non-recognition of Russian Tsarist rule in Poland was also seen in religious matters. It is known that the Tsar confirmed the appointment of Muslim leaders in Poland, but the Ottoman Sultan insisted on the education of Muslims and the education of their young leaders in Istanbul.

It is seen that some refugees came to Türkiye after the 1831 uprising in Poland. In those years, when the Sublime Porte took the Polish general Chrzanowski Wojciech into its service, it faced protests from the Austrian, Russian, and Prussian ambassadors. Chrzanowski was a participant in the Polish uprising. When the uprising was suppressed, he went to Austrian Galicia, then to Belgium and England, where he accepted British citizenship. Although generally disliked by refugee Poles, he was trusted and favored by Prince A. Czartoryski. Thus, with the recommendation and support of the exiled leader Adam Czartoryski, he was sent to Türkiye by the British government to participate in military reform efforts.

He came to Istanbul for the third time in 1838. In those years, the Ottoman army was still undergoing modernization efforts. The state had not yet overcome the rebellion of Mehmet Ali Pasha, the Governor of Egypt. Under these conditions, he was welcomed and put to work by the Ottoman administrators as a talented general. He focused on reforming the necessary troops for a successful defense against He focused on reforming the necessary troops for a successful defense against Mehmet Ali Pasha. Serasker Husnu Pasha appointed him as an advisor to Hafiz Pasha, the Commander of the Anatolian Army.

He went to Diyarbakir with Polish officers such as Zablowski and Kowalski in his entourage. Upon this appointment, Prussian Ambassador Konismarg, Austrian Chargé d’affaires von Klezl, and Russian Chargé d’affaires Boutiev successively made protests. In response, British Ambassador Ponsonby took the side of the Ottoman Government against these protests, stating that he was a British citizen. Austrian Prime Minister Prince Metternich sent the following note to the British Foreign Office in those years: “It would be understandable to send a genuine British general for the reform of the Ottoman army, but we cannot approve of a British-ized Pole being there.”

Thus, all three states tried to prevent the appointment of the Polish general. The Prussian ambassador even threatened the Sublime Porte by stating that no Prussian officer would be requested from them for reform work from then on. Despite all these, the general was sent to Diyarbakır with the other Poles in his entourage and was received with a military ceremony by Hafız Pasha at the army headquarters.

The general’s services, along with those of many others, contributed to some of the breakthroughs of the army, which had not yet completed its organization. He had come to Türkiye three times, and on his second visit, he served in the Ottoman army as a commissioned officer. Thus, he participated in the organization of the army’s training and administration and even formed a cavalry unit in Baghdad. When the Crimean War broke out in 1853, the Ottoman State called him back into service and wanted him to be a divisional commander in the Caucasus, but he could not participate in this war.

Refugee officers of the Ottoman Army

In 1849, the Hungarian revolution seemed to succeed at first. Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph, in desperation, after a long hesitation, asked the Russian Tsar for help. Nicholas I was pleased. Since at least two Polish generals, who had drawn his anger and hatred during the 1831 Polish uprising, were on the side of the Hungarian revolutionaries, he could now eliminate them.

Nicholas I did not delay in sending 200,000 soldiers to Hungary under the command of the ruthless General Paskevich. The Hungarians were in no position to resist this tremendous assault and force. Lajos Kossuth, an important figure of the Hungarian revolution, took refuge in Türkiye and left the command to the talented Hungarian General Gorgey. Gorgey directly surrendered to the Russians and contacted them, excluding the Austrians. Thus, Paskevich sent one of his famous reports to the Tsar: “Hungary is at Your Majesty’s feet.”

With this statement, Gorgey had succeeded in infuriating the Austrians, and Paskevich had also angered the Austrians because he had taken Gorgey and his entourage under his protection and was not handing them over to the Austrians. Whereas, the Tsar was punishing the captured Polish warriors in the most merciless way. The situation of the Poles was really difficult, and they found salvation in taking refuge in Türkiye.

When the Hungarian revolution failed in 1849, Hungarian warriors and politicians, and their allies, a large number of Poles and some Italians, took refuge in the Ottoman Empire. Among the Polish refugees was General Bem. General Josef Bem converted to Islam after a while and was ceremoniously received by Vidin Commander Ziya Pasha as Murat Pasha. Some officers and soldiers converted to Islam with him, but a church was allocated in Vidin Castle for those who did not change their religion. Apart from the generals mentioned above, there were three colonels and about ten majors.

In September 1849, there were 6,778 refugee warriors in Vidin Castle alone, about 1,200 of whom were Polish. Sultan’s representative Ahmet Efendi read the edict sent by Abdulmecid to the refugees and said the following words:

“I declare on my honor and absolutely that you will not find a nobler and more generous protection anywhere than here. Our master Sultan Abdulmecid Khan protects you. If any of you want to stay with us, you will be appointed to a position similar to your former position and rank in the army or in industry and administration without having to change your religion, but for those who want to leave our country, their departure to Malta will be ensured.“

Despite the incessant protests of Austria and Russia, the refugees were not returned. As early as August 1849, the letter written by Tsar Nicholas I to Sultan Abdulmecid, demanding the return of the Poles, was dismissed by the Sublime Porte. Count Radzivil, the extraordinary plenipotentiary who jointly represented Austria and Russia in this matter, was also forced to leave Istanbul in September 1849 without achieving his goal regarding the refugee issue. Unlike the Hungarian refugees, a large portion of the Polish refugees remained in Türkiye.

They were appointed to positions equivalent to their former duties in military, administrative, and industrial fields. For example, General Bem, who converted to Islam and became Murat Pasha, was appointed as the Commander of the armies on the right bank of the Danube (Vidin, Ruscuk, Silistra). The appointment of Murat Pasha to this position triggered strong protests from the Austrians and Russians.

Similarly, those who converted to Islam received new positions there. In 1849, Omer Pasha (later the commander-in-chief of the Ottoman armies in the Crimean War), whom the Austrians and Russians disliked and who was the Commander of the Rumelian armies, was a figure constantly subjected to protests by these two states for allegedly protecting the Poles in Vidin and forcing them to convert to Islam. Although the Ottoman administrators vehemently denied such accusations, it is clear that the Polish refugees thus became Ottoman subjects and obtained a guarantee against being sent back.

Refugee Polish officers shaped the modern Ottoman army

These Polish officers, who became Ottoman subjects, were the pioneers of modernization in the Ottoman Tanzimat era. One of them, Count Konstantin Borzecki (Mustafa Celalettin Pasha after converting to Islam, grandfather of the great Turkish poet Nazım Hikmet), introduced new methods in artillery, rendered services in the field of cartography in the army, and wrote the first pioneering work of Turkish nationalists.

He continued this brilliant career and was martyred on the battlefield in the Montenegrin War with the rank of Mirliva. Another Polish officer who rose to the rank of Mushir in Ottoman service was Mahmut Hamdi Pasha.

General Zamowinski, Sobieszcanski, and 17 other officers served in the Ottoman army without changing their religion. Similarly, General Bilinski (Saadettin Nuzhet Pasha after converting to Islam) and General Michael Czaykowski (Sadik Pasha) were two pioneering figures of the Ottoman military reforms of this period.

In this context, it is also necessary to mention Captain Stanislas Count Ostrorog, who did not change his religion. He is the head of a family that played a brilliant role in Istanbul’s cultural life for a long time, not just with his military services. The Ostrorog Mansion on the Bosphorus is a memory of this family.

The resolute and courageous stance of the Ottoman Empire in not returning the refugees found ardent supporters in European capitals such as Paris and London, and public opinion in the European world turned in favor of the Turks. One day in 1850, crowds in the streets of London unharnessed the horses of the carriage of Ottoman Ambassador Kostaki Musurus Pasha and pulled his carriage to the embassy in a procession with cheers.

Musurus Pasha was among those who gave an example of active and successful diplomacy in the refugee issue. The refugee problem, in a way, dragged the Ottoman Empire into a new war: the Crimean War. Among the memories that remain from this period are Polonezkoy, established by Polish refugees near Istanbul, and the Polish refugees of all ranks and degrees who rendered great services to Ottoman modernization, that is, Ottoman-citizen patriots.