Viennese origins with Ottoman influence: Surprising history of Parisian croissant

A group of croissants, each with a distinct personality, engage in a lively debate at a Parisian cafe, with Eiffel Tower views and coffee cups steaming (photo by Unreal)

A group of croissants, each with a distinct personality, engage in a lively debate at a Parisian cafe, with Eiffel Tower views and coffee cups steaming (photo by Unreal)

The humble croissant, a symbol of Parisian mornings and delectable indulgence, holds a surprising secret: it’s not actually French. This historical quirk has sparked renewed debate, particularly when it comes to the “correct” way to eat this beloved pastry.

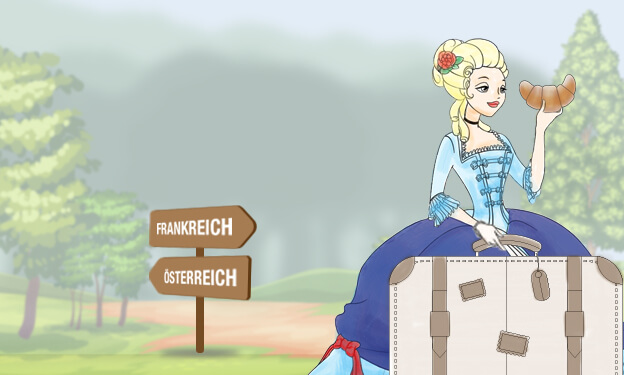

In reality, croissants are Viennese, created to celebrate the Habsburgs’ defeat of the Ottoman Empire at the Battle of Vienna in 1683. The crescent shape is a nod to the Ottoman flag. Legend has it that Marie Antoinette, born in Vienna, introduced the croissant to Paris in 1770. However, croissants only became widespread in France in the mid-19th century, with the first description of a Viennese baker in Paris appearing in 1838.

Romantic image of Parisian croissant

When you think of a fresh, flaky croissant, you likely imagine Paris: a lazy morning on the Left Bank, a small round table, Le Journal in hand and a steaming cup of cafe au lait.

That warm, buttery croissant, crispy on the outside, light and fluffy on the inside, seems quintessentially French. However, delve deeper, and you will find its true origins.

We hate to break it to you, but that croissant you’re enjoying as you gaze lovingly at the Eiffel Tower is not French.

Linguistic clues and historical roots

Croissants are a type of viennoiserie pastry, linking them back to Vienna, the birthplace of croissants. The ancestor of the modern croissant is the “kipferl”, dating back to the 13th century, often filled with nuts or other fillings.

Kipferl, possibly linked to ancient Egypt, is also a form of rugelach, a Jewish pastry of Ashkenazic origin, denser and sweeter than the modern croissant.

In the 17th century, the dough began to evolve. Viennese bakers, during the 1683 Ottoman siege of Vienna, reportedly created a crescent-shaped pastry in celebration of their city’s defenders thwarting the Ottoman tunneling efforts. This pastry, named after the German word “kipferl” for crescent, symbolized Vienna’s victory over the Turks.

The first verified evidence of croissants in France comes from August Zang, an Austrian baker who opened the Boulangerie Viennoise in Paris in the early 1800s, serving treats like the kipferl. Parisians, enamored with the flakier version, began calling them croissants due to their crescent shapes. In 1915, Sylvain Claudius Goy wrote the recipe we know and love today.

Croissant’s Ottoman connection

Though we associate croissants with French cuisine, their story is far more intricate, rooted in Austrian culinary traditions with significant Ottoman influences.

The croissant’s history is often linked to the kipferl, a yeast-based pastry made in Austria since the 13th century. However, the story takes a dramatic turn in 1683, during the Second Siege of Vienna by the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans attempted to breach the city walls by tunneling beneath them, but Viennese bakers, working through the night, heard the sounds and alerted the city’s defenders.

To commemorate their role in saving Vienna, bakers created a crescent-shaped pastry, inspired by the Ottoman flag. Some say it was a tribute, while others believe it was mocking the defeated Ottoman forces. Regardless, the kipferl gained its crescent shape and eventually made its way to France.

Marie Antoinette’s influence

France first encountered the croissant in 1770 when Marie Antoinette, the Austrian archduchess, married the French Dauphin. She brought her love for the crescent-shaped pastry to Paris. By 1774, as queen of France, she had introduced the croissant to the royal court, where it quickly gained popularity and spread beyond the palace walls.

French adaptation

Over time, the recipe evolved. By the mid-19th century, the croissant as we know it today had taken shape in France, blending Austrian baking techniques with French culinary finesse. This transformation solidified its status as a beloved French delicacy, despite its foreign roots.

The croissant, with its buttery, flaky layers, is celebrated worldwide as a quintessential French pastry. However, its origins are deeply intertwined with Austrian and Ottoman history.

From the bakers of Vienna to the royal courts of Paris, the croissant’s journey is a testament to the rich, multicultural influences that shape our culinary traditions.