130,000-year-old baby mammoth found in Siberia unveils prehistoric secrets

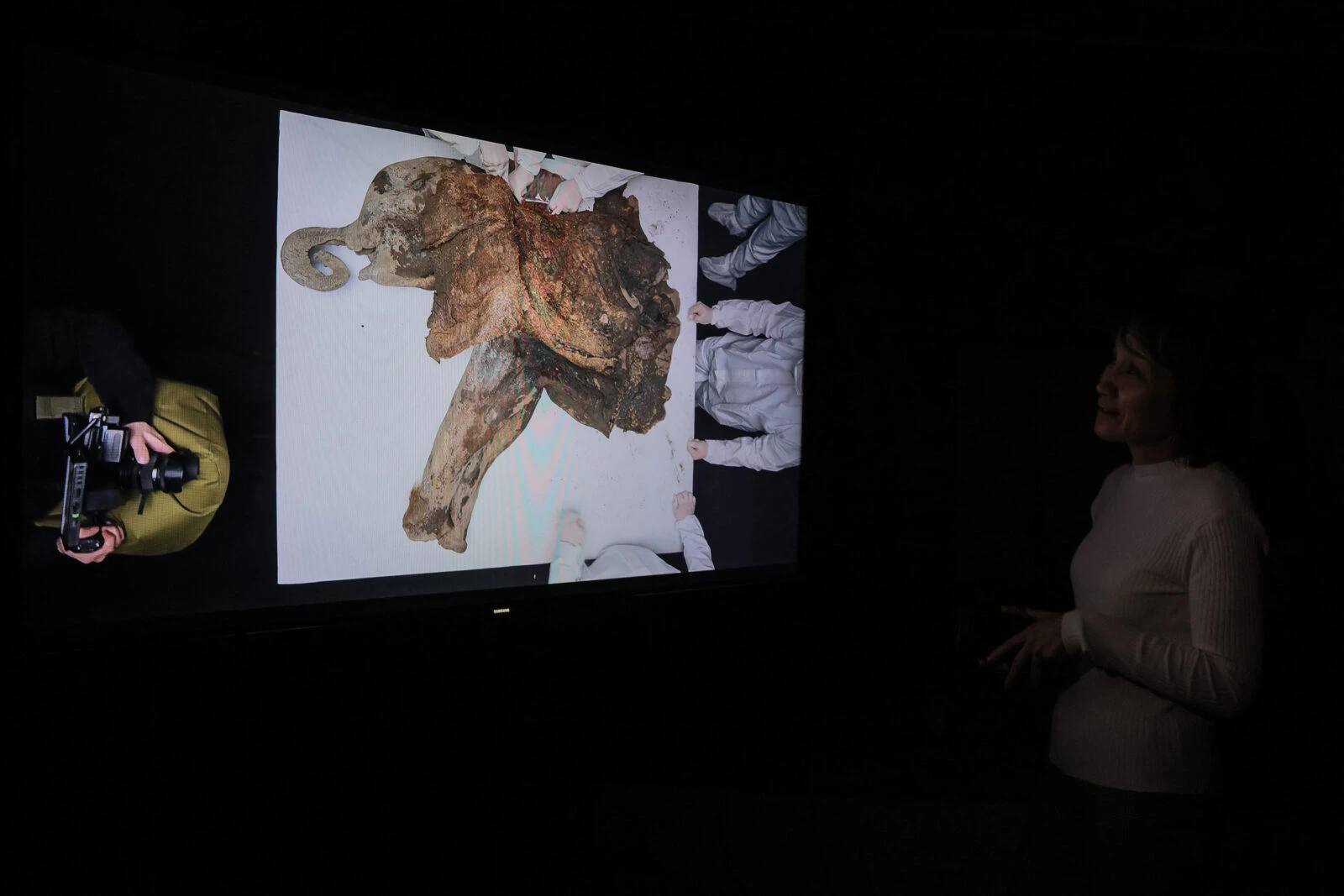

Scientists perform a necropsy on baby mammoth nicknamed "Yana" at the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, March 27, 2025. (AFP Photo)

Scientists perform a necropsy on baby mammoth nicknamed "Yana" at the North-Eastern Federal University in Yakutsk, March 27, 2025. (AFP Photo)

Deep in a laboratory in Russia’s far east, scientists delicately made incisions, carefully extracting samples from a remarkably well-preserved baby mammoth. The scene resembled a forensic post-mortem, but the subject under examination was an ancient creature that roamed the Earth approximately 130,000 years ago.

Nicknamed Yana, after the river basin where she was discovered last year, this mammoth calf is offering scientists an unprecedented opportunity to study prehistoric life. Due to the effects of climate change, the permafrost that had encased Yana for millennia is now thawing, revealing her astonishingly intact body.

A glimpse into the past: Yana’s remarkable preservation

Yana’s skin retains its original greyish-brown color, with tufts of reddish fur still clinging to her body. Her trunk remains curved and points toward her mouth, while her eye sockets are well-defined. Her sturdy legs resemble those of a modern elephant, making her one of the best-preserved mammoth specimens ever found.

“This necropsy is an opportunity to peer into the past of our planet,” said Artemy Goncharov, head of the Laboratory of Functional Genomics and Proteomics of Microorganisms at the Institute of Experimental Medicine in Saint Petersburg.

The calf’s internal organs and soft tissues have remained intact, allowing scientists to conduct genetic analysis and study ancient bacteria, plants, and spores that could shed light on the ecosystem she once inhabited.

Frozen in time: How Yana survived millennia in permafrost

Yana, measuring 1.2 meters (nearly 4 feet) at the shoulder and 2 meters in length, weighed approximately 180 kilograms (nearly 400 pounds) at the time of her death. Her exceptional state of preservation is attributed to the Sakha region’s permafrost, a natural deep freeze that has kept prehistoric creatures largely untouched for tens of thousands of years.

The ongoing necropsy at the Mammoth Museum, located in Yakutsk, has provided an extraordinary opportunity for researchers. Clad in sterile bodysuits, goggles, and facemasks, a team of zoologists and biologists meticulously examined the mammoth’s front quarters, which had separated from the rest of her body when it was exposed.

“We can see that many organs and tissues are very well preserved,” said Goncharov. “The digestive tract is partially intact, with the stomach and fragments of intestines, including the colon, remaining in place.”

By analyzing these samples, scientists hope to uncover ancient microorganisms and explore their evolutionary connections with present-day bacteria.

Searching for clues: Investigating cause of death

Scientists are still trying to determine the exact cause of Yana’s death. Her well-preserved remains offer clues, but there is no immediate evidence of injury or illness.

“We are trying to reach the genitals,” explained Artyom Nedoluzhko, director of the Paleogenomics Laboratory at the European University in Saint Petersburg. “Using special tools, we aim to collect material that will help us understand the microbiota that lived inside her when she was alive.”

The necropsy is also revealing vital information about mammoth development. Yana’s “milk tusks”, a feature similar to baby teeth in humans, suggest she was over a year old at the time of her death. Unlike adult mammoths, juveniles first develop these smaller tusks, which eventually fall out as they grow.

Permafrost melting: A warning for the future?

Yana’s exposure is a direct consequence of thawing permafrost, a phenomenon scientists attribute to global warming. While this has led to the discovery of numerous well-preserved Ice Age creatures, it also raises concerns about the potential release of ancient pathogens.

“There are hypotheses suggesting that some pathogenic microorganisms have been preserved in the permafrost,” said Goncharov. “As the ice melts, these microbes could enter water systems, plants, animals—and even humans.”

The study of such ancient microbiology is becoming increasingly crucial as researchers examine the biological risks associated with climate change. Understanding the evolutionary history of these microorganisms could be vital in predicting and preventing potential threats.