When and how hookah culture reached Türkiye

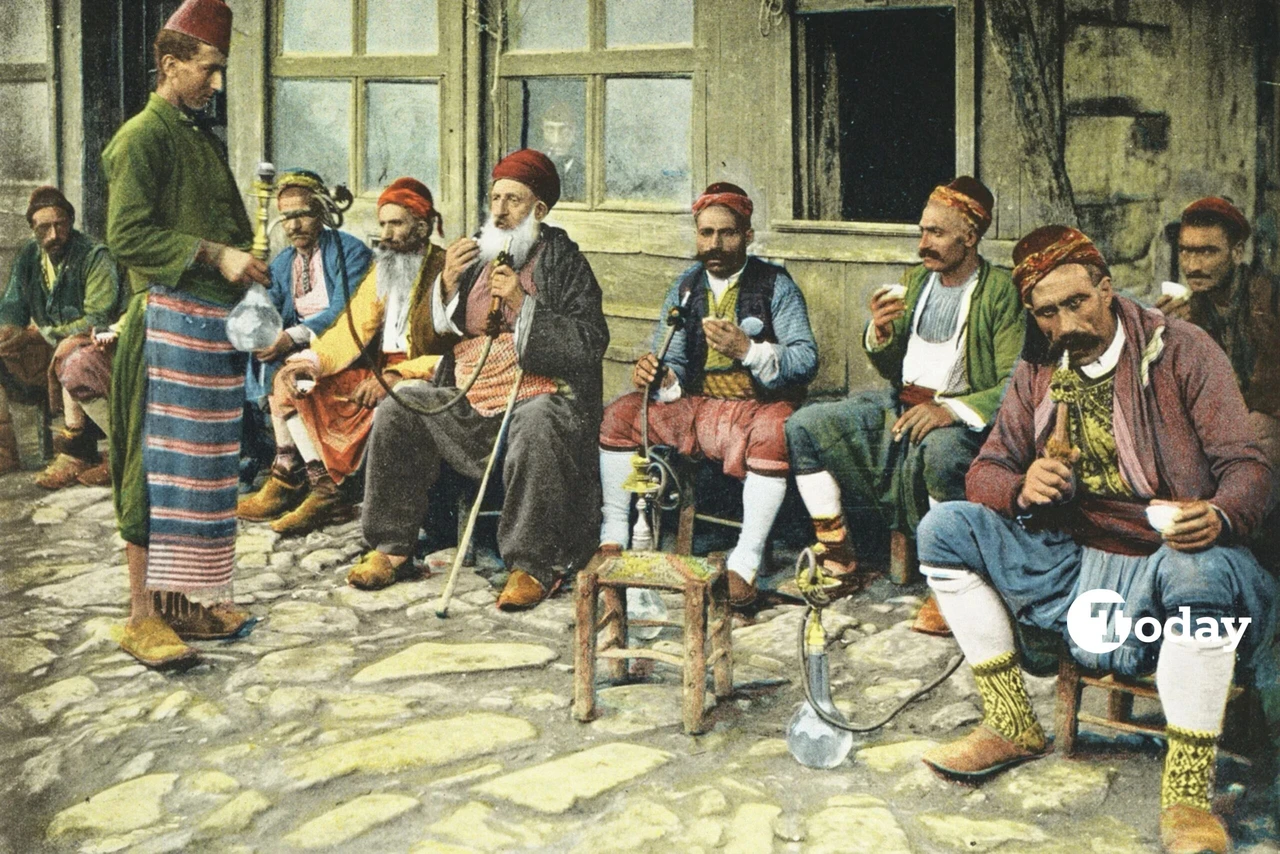

Men smoking hookah in front of a coffeehouse, Istanbul, Türkiye, 1898. (Photo via Flickr)

Men smoking hookah in front of a coffeehouse, Istanbul, Türkiye, 1898. (Photo via Flickr)

The journey of the hookah—known locally as “nargile”—begins in the 16th century in Mughal India, where aristocrats of the Babur Empire enjoyed smoking tobacco through coconut-shell bowls and bamboo tubes. According to Professor Ekrem Bugra Ekinci, these early hookahs softened the harshness of smoke by filtering it through water, marking the birth of a practice that would soon become a cultural mainstay across the Islamic world.

From India, the hookah made its way to Safavid Iran. There, Persian craftsmen elevated the device into an artistic object and symbol of refinement, embellishing it with intricate forms. Egyptians adopted the device next, calling it nargil—a name born of the local pronunciation that transformed the “c” into a “g” sound.

Arrival in Ottoman lands

The hookah likely entered Ottoman Türkiye during the reign of Sultan Murad IV (1623–1640). By the 17th century, Istanbul’s Bayezid district hosted dedicated hookah cafes, or nargileci kahvesi, where patrons gathered to enjoy this leisurely pastime. According to Professor Ekinci, hookah use was not limited to public spaces; it was also a popular feature of private homes and outdoor picnics.

European painters of the era often depicted Ottoman women leisurely puffing on ornate hookahs. So iconic was the hookah as a symbol of the East that European travelers in Turkish dress posed for portraits, hookah hoses in hand.

At Ottoman porcelain factories like Beykoz and Yildiz, hookahs became genuine works of art. “As in everything else,” Professor Ekinci writes, “the Turks brought their sense of aesthetics to the hookah, creating a distinct Ottoman hookah culture.” Even riddles were written about the device—one of them describing it as a vessel that sighs and smokes while sinking into pleasure.

Hookah culture: A symbol of prestige and ritual

The hookah also entered Western imagination. During his visit to Istanbul, Hungarian composer Franz Liszt was presented with a silver hookah by Sultan Abdulmecid. French writer Pierre Loti, enamored with Istanbul, traveled with his personal ‘nargile’. German general Helmuth von Moltke recalled Turks infusing their tobacco with rose or cherry petals, observing the joyous dance of the smoke through the bubbling water.

In Ottoman society, hookah was enjoyed by everyone—from high-ranking officials to common workers. It was not uncommon for the wealthy to employ servants dedicated solely to preparing and serving hookah. According to Professor Ekinci, seasoned users were easily identified—such as a Darussafaka teacher whose mustache was stained yellow by years of smoking tombeki (hookah tobacco).

By the late 19th century, hookah culture had permeated many corners of society, from bureaucrats to Sufi dervishes. One memoir recounts: “After dhikr, we drank coffee and smoked hookah. For our master believed it cleared the mind.”

Yet not everyone embraced the habit. Hookah, like snuff and other tobacco products, was seen by some as a frivolous vice. Literary figures such as Omer Seyfeddin even portrayed it as a character flaw. One notable cautionary tale tells of a guest at the mansion of Suphi Pasha falling asleep while smoking, sparking a fire that destroyed the entire building.

The Turkish touch

The traditional Ottoman ‘nargile’ consists of four key parts: the body (govde), water jar (sise), hose (marpuc), and bowl (lule). Each component was crafted with care. The body, often metal or porcelain, was elegantly shaped. The water jar, typically clear glass, allowed users to observe the movement of smoke and water. According to Professor Ekinci, architect Mimar Sinan is said to have tested the acoustics of Suleymaniye Mosque using the bubbling sound of a smokeless hookah.

The hose, made of supple leather, could stretch several feet. Its finest versions came from Homs, Syria, and were once sold in a dedicated bazaar in Istanbul’s Mahmutpasa district. The bowl, holding the tobacco, was made from clay, ceramic, or glass and sometimes housed in a finely ornamented silver casing. Even the hookah tongs (masa) were artfully designed—some hidden inside walking sticks or knife handles as clever novelties.

In Türkiye, artisans crafted crystal, gilded, and gemstone-encrusted hookahs, turning the device into a visual statement of taste. While Turkish-grown tombeki from Antakya and Konya was valued, the finest tobacco came from Isfahan. In the 20th century, flavored hookah tobacco emerged—muassel—infused with molasses, fruit essences, or glycerin. Apple, grape, mint, and even chocolate became popular variants.

Rituals and sayings

Hookah smoking came with its own code of etiquette. Devotees adhered to the “Four A’s”: masa (tongs), mese (oak coal), kose (a quiet corner), and Ayse (a helper). Enthusiasts would personally clean and assemble their device, preferring not to trust cafe staff with the ritual.

Hookah was also a central element of hospitality. Even in wartime, Ottoman soldiers would find time to puff on their pipes. The bubbling of a hookah was likened to music or even majesty—Abdulhak Sinasi Hisar once said his cat purred “with the majesty of a hookah.” Refik Halid Karay compared its hiss to a factory whistle.

As Professor Ekinci notes, Turkish folk culture is rich in hookah-related sayings:

“No thief enters the house of a hookah smoker” (because the smoker’s cough scares them away).

“A hookah smoker never sees the doctor” (because he doesn’t live long enough to need one).

Unpleasant drinks were even dismissed as “hookah water.”