Rare Andalusian astrolabe discovered: What do Arabic, Hebrew inscriptions represent?

A rare 11th-century astrolabe bearing inscriptions in Arabic and Hebrew inscriptions was discovered in a museum in Verona, Italy.

According to Cambridge University, the discovery is valuable as Muslim, Jewish and Christians in Spain, North Africa and Italy adapted and translated the astrolabe for centuries. These instruments are known to be the world’s first smartphone, a portable computer that could be used for several purposes.

The discovery was made by Cambridge University’s history faculty member Federica Gigante, who published the research in the journal “Nuncius.”

The astrolabe, now preserved in the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo, is a testament to the contacts and exchanges between Arabs, Jews and Christian Europeans in the medieval and early modern periods.

Gigante began her research when she stumbled upon a newly uploaded image of the astrolabe Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo.

“This isn’t just an incredibly rare object. It is a powerful record of scientific exchange between Arabs, Jews and Christians over hundreds of years,” Gigante said.

Gigante, an expert on Islamic astrolabes, analyzed the leading scientific, design, construction and calligraphic features to determine the date and place of construction of the “Astrolabe of Verona”.

She identified the object as Andalusian, and from the engraving style and the scales’ arrangement on the reverse, she matched the astrolabe to instruments made in Andalusia, the Muslim-ruled region of Spain in the 11th century.

Gigante suggested that the astrolabe may have been made when Spain’s Toledo was a thriving center of coexistence and cultural exchange between Muslims, Jews and Christians.

The astrolabe contains Muslim prayer lines and names arranged to enable its original users to perform daily prayers on time.

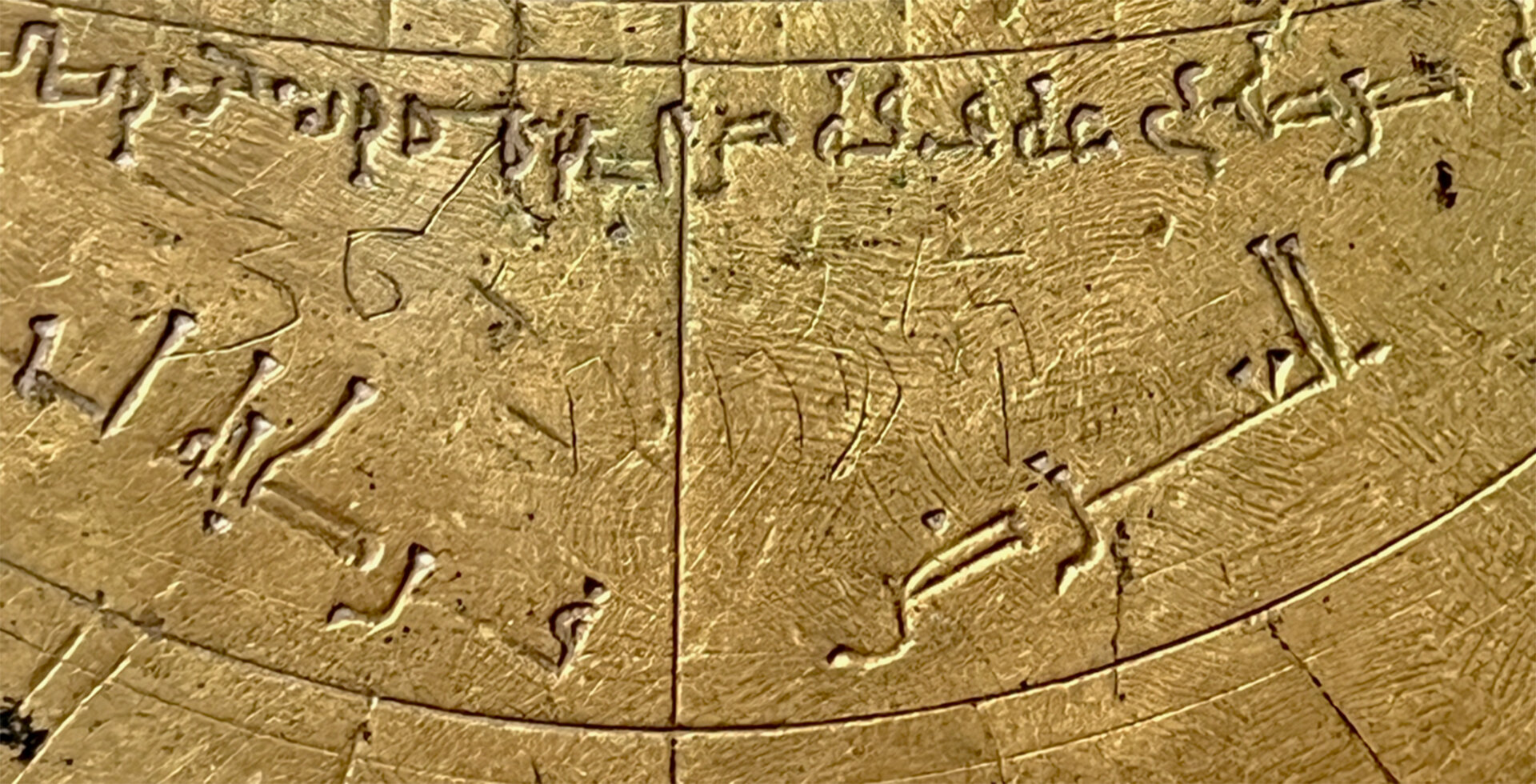

The signature on the astrolabe reads “For Isḥaq (…) The work of Yunus”. This was engraved after the astrolabe was made, probably for a later owner.

Isḥaq and Yunus, Isaac and Jonah in English could be Jewish names written in Arabic script. This detail suggests that at some point the object circulated within the Sephardic Jewish community in Spain, where Arabic was the spoken language.

A second added plate is inscribed for typical North African latitudes, suggesting that the object was used at another point, perhaps in Morocco or Egypt.

Shreds of evidence reveal that more than one hand added the Hebrew inscriptions on the astrolabe.

One set of additions is deeply and neatly carved, while a different set of translations shows a very light, uneven hand.

According to research, Hebrew additions and translations indicate the object left Spain or North Africa at some point and circulated among the Jewish diaspora community in Italy, where Arabic was not understood and Hebrew was used instead.

One of the Hebrew additions to the astrolabe reads “34 and a half” instead of “34 ½”, suggesting that the engraver was not an astronomer or astrolabe maker.

The other Hebrew inscriptions are translations of the Arabic names of astrological signs such as Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces and Aries.

The astrolabe contains corrections not only in Hebrew but also in the numerals used today.

All over the plates of the astrolabe are lightly drawn marks in Western numerals, some even more than once, translating and correcting the latitude values.

Gigante thinks it is highly likely that these additions were made for someone who spoke Latin or Italian in Verona.

The astrolabe has a “rete” – a disk with holes representing a map of the sky – one of the earliest known astrolabes made in Spain.

Remarkably, it is similar to the rete of the only surviving Byzantine astrolabe, created in 1062 A.D., and to the earliest European astrolabes made in Spain on the model of Islamic astrolabes.

Calculating the star’s position offers a tentative timeframe for the celestial canvas from which it is composed.

By analyzing the position of the stars on the rete, it is possible to calculate that they were placed in the position they had in the late 11th century, matching other astrolabes, for example, in 1068 A.D.

The astrolabe is thought to have entered the collection of the Veronese nobleman Ludovico Moscardo (1611-81) before passing it to the Miniscalchi family.

The family founded the Fondazione Museo Miniscalchi-Erizzo to preserve their collection.

Gigante explained the instrument is a testament to shared scientific cultures across the world.