Puckle gun: Failed British 1718 machine gun attempt, designed to kill Ottomans with square bullets

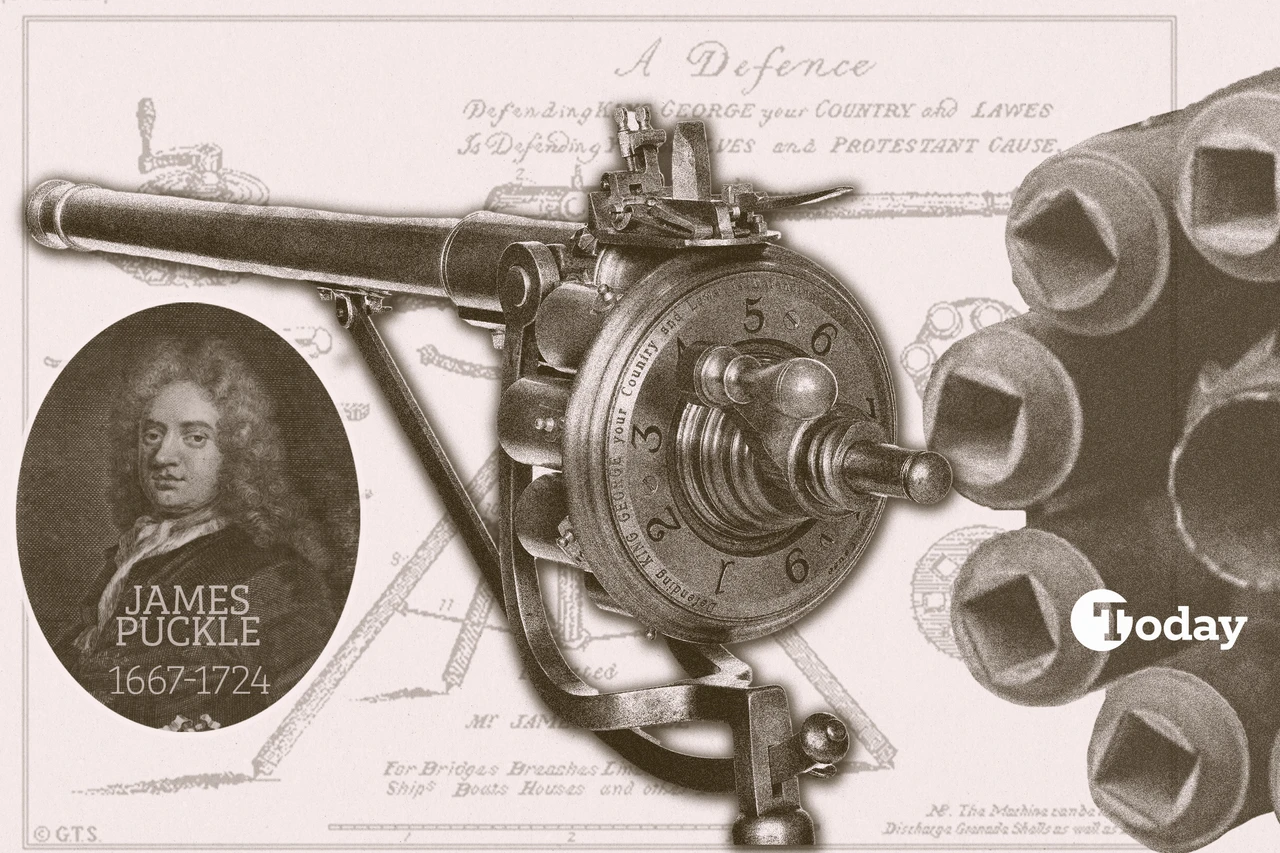

A collage depicting puckle gun prepared by Türkiye Today team.

A collage depicting puckle gun prepared by Türkiye Today team.

In 1718, James Puckle, a London lawyer, introduced one of the earliest attempts at an automatic firearm—an innovation aimed not just at improving European naval defenses but also at addressing the geopolitical and religious tensions of the time. The Puckle gun, designed with a controversial dual-ammunition system, specifically targeted Ottoman forces and Muslim Turks, reflecting the era’s deep-seated hostilities between Christian Europe and the Ottoman Empire.

Square bullets for Muslims, round bullets for Christians

The Ottoman Empire, controlling much of Southeast Europe, North Africa, and the Mediterranean, posed a considerable threat to European powers during the early 18th century.

Ottoman forces, including fast-moving navy forces, frequently attacked European ships, disrupting maritime trade. Puckle’s invention was intended to be a naval defense weapon to counter these attacks, with an interesting twist on the ammunition used.

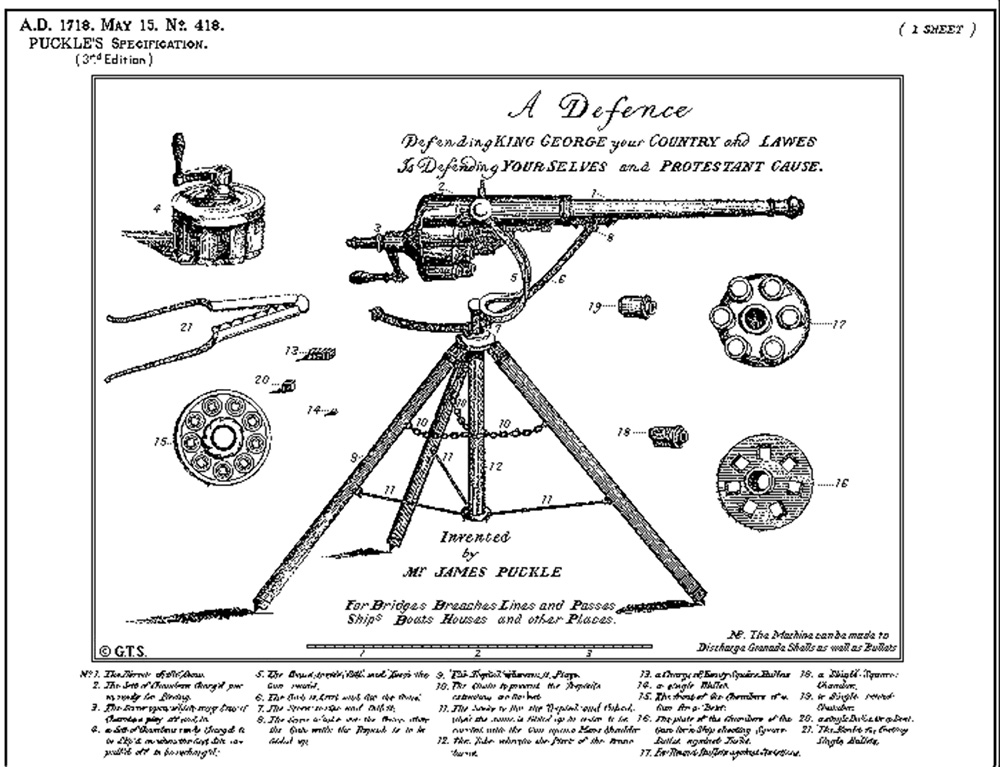

What set the Puckle gun apart was its design for two types of ammunition. It could fire conventional round bullets at Christian enemies but was equipped with square bullets for use against Muslim Turks.

According to Puckle’s patent, these square bullets were intended to cause more severe wounds, with the stated goal of “convincing the Turks of the benefits of Christian civilization.” This ammunition choice was a stark reflection of the religious and political conflicts between the expanding Ottoman Empire and Christian Europe.

Tripling the fire rate of muskets against agile Ottoman raids

By the early 18th century, the Ottoman Empire was at the height of its power, stretching into southeastern Europe and threatening to push further into the continent. Along with territorial ambitions, Ottoman forces disrupted European trade routes in the Mediterranean with lightning-fast raids. Small, agile Ottoman ships were too quick for traditional broadside cannons, making them formidable adversaries for European merchants and navies alike.

Puckle’s gun was designed to fill this gap in naval defense. Mounted on a tripod, it featured a single barrel with a revolving cylinder capable of firing up to nine shots per minute—far outpacing the standard musket of the time, which could only manage about three shots per minute under optimal conditions.

This rapid-fire capability was seen as a potential game-changer in fending off the swift Ottoman boats.

Why did the Puckle gun fail?

Despite its groundbreaking design, the Puckle gun faced significant challenges that ultimately limited its success. During public demonstrations, such as one in 1722, the gun showcased its rapid-fire capabilities by firing 63 shots in seven minutes—an impressive feat for the time. However, the gun’s flintlock mechanism, which was responsible for igniting the gunpowder to fire each shot, was prone to malfunction. This unreliability undermined its potential as a reliable weapon for military use.

The British military, while initially intrigued, ultimately rejected the Puckle gun after testing. The unreliability of its firing mechanism and the technological limitations of the period meant it was never adopted for widespread use. Additionally, the weapon failed to attract enough investors for mass production, and only a few units were ever made. John Montagu, the 2nd Duke of Montagu, purchased at least two of the guns for an expedition to capture St. Lucia and St. Vincent in 1722, but the expedition failed, and there are no records of the guns being used in combat.

The Puckle gun’s legacy

Although the Puckle gun never saw combat and was not adopted by any military forces, its design is notable for being one of the earliest attempts at creating a rapid-fire weapon—a precursor to the modern machine gun. The gun’s dual-ammunition system, designed specifically to target Muslim Turks, highlights the religious and geopolitical tensions that shaped European military innovations in the 18th century.

Ultimately, the Puckle gun stands as a historical curiosity, reflecting both the technological ambition of its inventor and the religiously charged conflict between Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Though it failed to leave a lasting impact on warfare, it offers insight into the lengths to which European inventors were willing to go to defend against the perceived threat of the expanding Ottoman Empire.