Africa’s colonial history: How Ottoman Empire countered Belgian colonial ambitions?

Cartoon depicting Belgian King Leopold II (in the middle) at the Berlin Conference of 1884 (By engraver F. Marechal)

Cartoon depicting Belgian King Leopold II (in the middle) at the Berlin Conference of 1884 (By engraver F. Marechal)

By the late 15th century, Africa attracted the attention of European states, gradually becoming a new market. Initially, European control over Africa was established through missionary activities. However, from the 19th century onward, economic interests began to shape the continent as well. This period saw an increase in the influence of major European powers over Africa.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Africa became the subject of various treaties aimed at dividing the continent among European powers. Initially, countries like Portugal, Spain, France, England, and Belgium, which focused on coastal regions with activities such as slave trade, mining, and commerce, expanded their influence. Later, Germany and Italy also joined, further extending their impact.

Subsequently, European nations began sending exploration missions to discover the sources of major rivers like the Nile and the Congo. These expeditions led to numerous invasions and the acquisition of new territories for various European countries. However, disputes over the division of Africa, particularly in the Congo Basin, caused conflicts between European states.

Following these developments, Germany, seeking to acquire new territories in Africa, requested the organization of a conference with the support of France. In 1884-85, European states gathered in Berlin under the leadership of German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. They signed a treaty regulating the rights to navigate and trade on the Congo and Niger rivers.

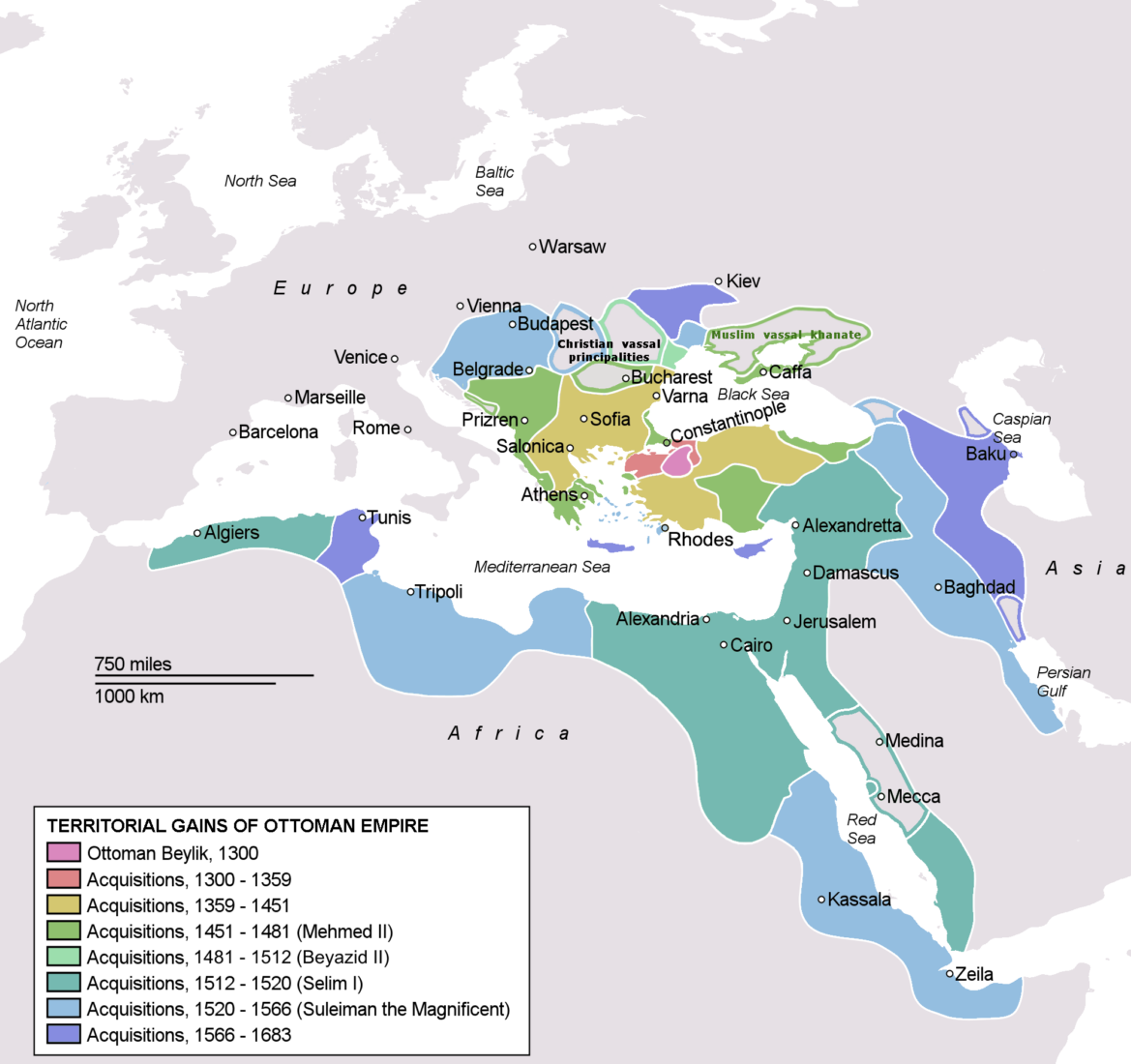

The conference, which also included the Ottoman Empire, formalized the division of Africa among European powers. The partitioning of the continent through bilateral treaties began, and Africa’s future continued to be shaped by European powers.

How did Belgium’s colonial expansion affect Ottoman-Belgium relations in late 19th century?

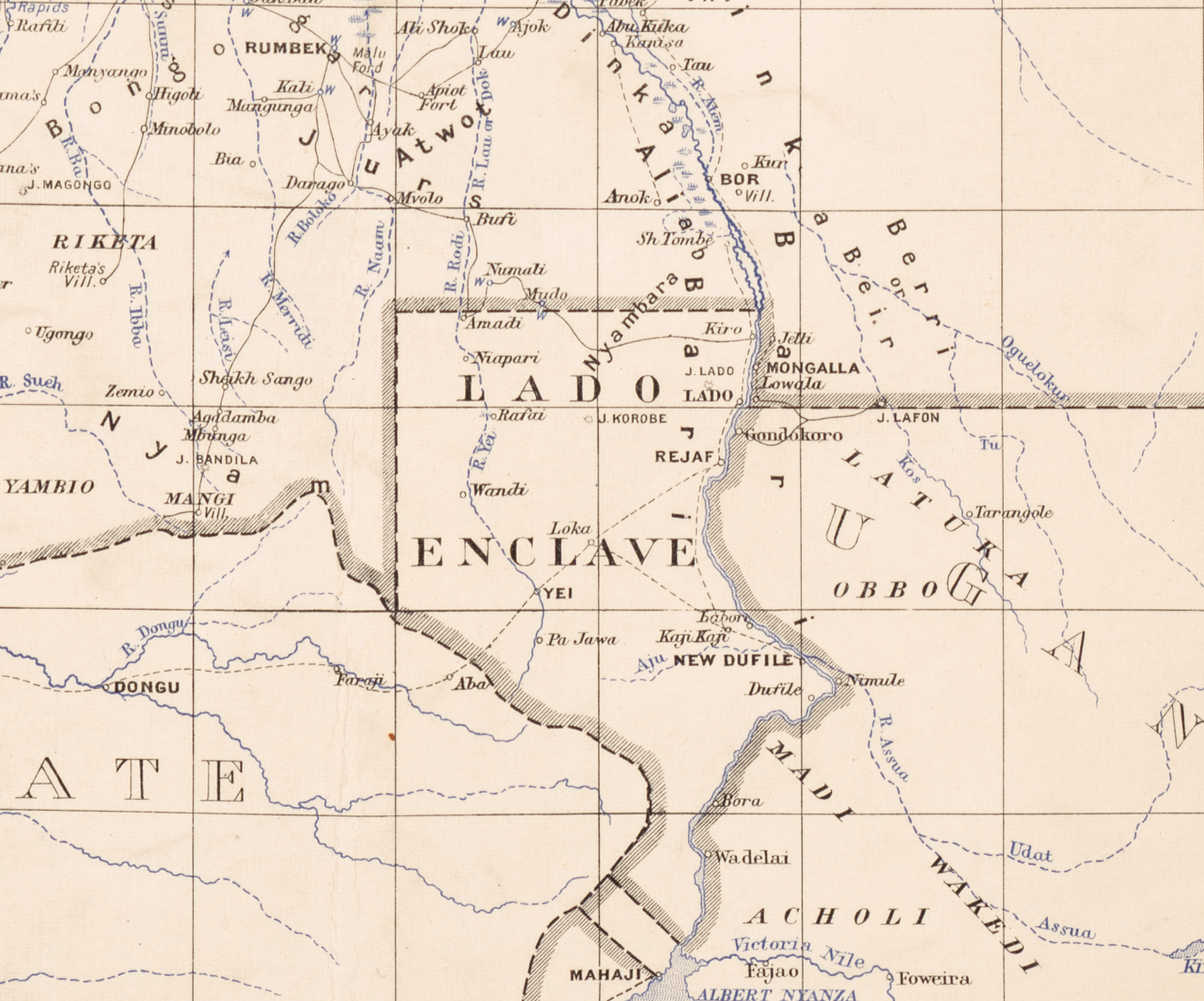

Belgium’s colonization efforts in Central Africa gained momentum toward the end of the 19th century through exploratory expeditions. During this period, Belgium’s activities through the Congo Free State led to significant developments, particularly concerning the lands of South Sudan north of Lake Albert. Belgium’s presence in this region drew the attention of other European powers, especially England. England sought to influence Belgium’s actions in the area to align with its own interests.

King Leopold II of Belgium’s exploration efforts aimed at acquiring new territories in the Congo basin began to show results swiftly. By the late 19th century, an exploration team under Belgium’s patronage reached Upper Egypt and planned to annex this region to the Congo Free State. This situation brought the issue of sovereignty to the forefront. Specifically, the Correspondance Politique newspaper, published in Vienna, featured a report on Aug. 27, 1893, about the invasion and annexation of the South Sudan region, sparking widespread discussions.

The newspaper addressed the matter of incorporating the Hatt-i Istiwa (Equatorial) province, governed by Emin Pasha in the service of the Khedive of Egypt, into Congo from the perspective of International Law. It highlighted that the Khedive of Egypt could not accept this situation without protest. Additionally, it was mentioned that Belgium would face protests from the states participating in the Berlin Conference.

According to the newspaper, the Hatt-i Istiwa province, a part of the Egyptian continent, had been captured and administered by Egyptian soldiers 20 years earlier. The Khedive of Egypt had the right to reject this situation, as the Ottoman Empire had secured recognition of its and Egypt’s jurisdiction over the Hatt-i Istiwa province during the Berlin Conference session on Jan. 31, 1885. The Congo government had no right to annex this province.

The Ottoman Empire took action to defend its rights in Egypt. Ambassador Rustem Pasha in London discussed the situation with the British Foreign Minister Lord Rosebery, indicating that they were aware of Belgium’s activities. Rosebery speculated that Belgium might be in Vadelay but stated that King Leopold was not informed about this matter. The Ottoman Empire planned to take necessary measures to protect Egypt’s rights in the region. The Egyptian Extraordinary Commission provided detailed reports to the Ottoman Empire regarding the events in South Sudan.

What is bloody history of today’s delicious Belgian chocolates?

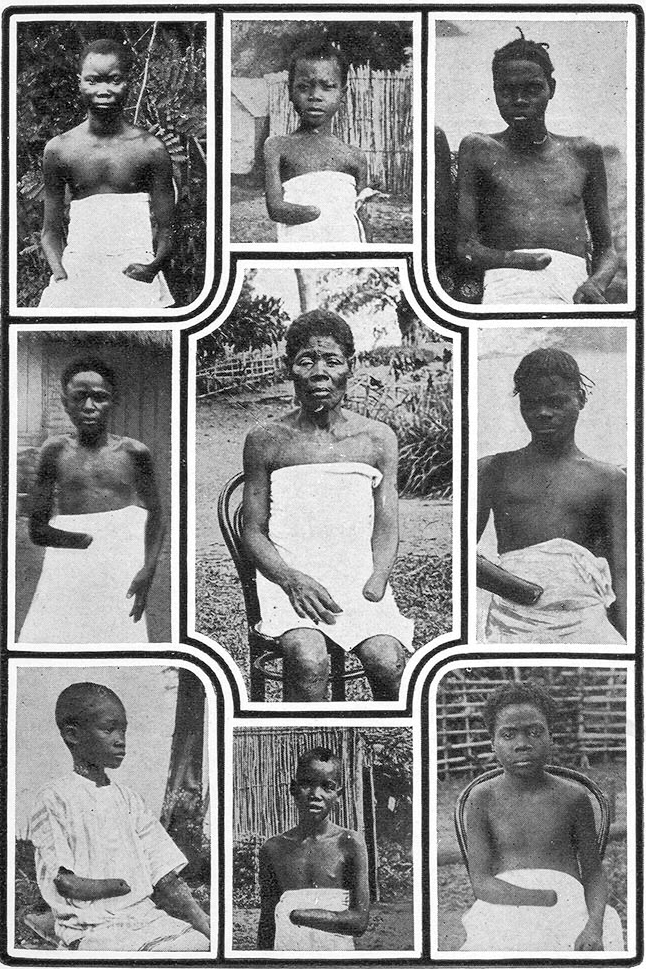

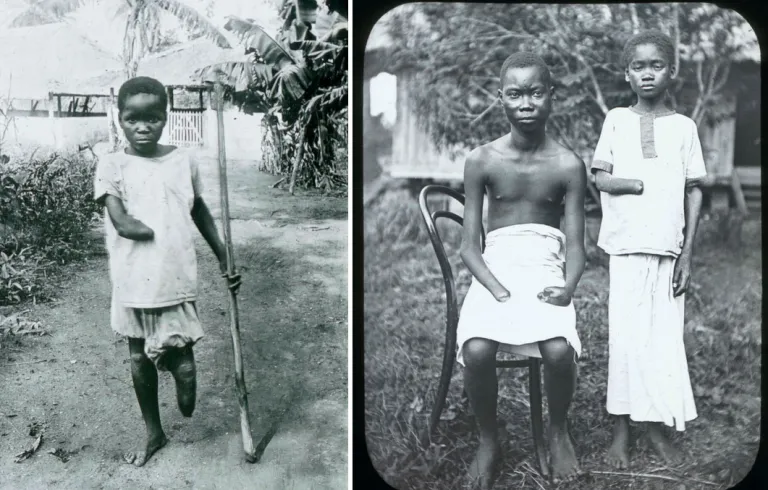

King Leopold II of Belgium’s brutal rule in the Congo left a dark mark not only on history books but also on the history of chocolate. During Leopold’s reign from 1885 to 1908, the people of the Congo endured horrific oppression; this period is known for the death of millions and the ruthless implementation of slavery.

Under Leopold’s rule, the Congolese were enslaved for rubber production. Alongside the forced rubber collection and violent ivory hunting, a horrific system of punishment was put into place. Those who failed to meet rubber quotas had their hands cut off. These severed hands were collected by Leopold’s security forces in special baskets and used to keep records of bullets and punishment costs. This practice inspired a traditional chocolate known as “severed hand chocolate.”

Looking at the history of chocolate produced in Belgium, it is evident that the cocoa used came from the Congo. While Leopold used the Congo as his personal possession, the cocoa that formed the basis of the chocolate industry was part of these horrifying practices. The chocolate Leopold presented to his “brothers” was considered the fruit of the bloodied labor of the enslaved Congolese. Chocolate became a symbol of Belgium’s colonial exploitation system.

Leopold’s cruelty in the Congo was not limited to severed hands. During the same period, “human zoos” were established in Europe, where people from the Congo and other colonial regions were exhibited. Today, modern examples of these practices continue in the U.S.

Leopold’s rule in the Congo marks one of the darkest periods in human history. Even seemingly innocent objects like chocolate should be remembered as part of this historical oppression. Leopold’s horrific legacy in the Congo serves as a reminder of the need to remember colonialism and human rights violations. Today, remembering this cruelty and exploitation is essential for both historical responsibility and justice.

1894 Anglo-Belgian Agreement signed without Ottoman Empire

The treaty, signed in Brussels on May 12, 1894, was between England and King Leopold II of the Congo Free State. The first article of the treaty determined the boundary between the Congo Government and English colonies, while the second article stipulated that England would cede a 25-kilometer area from the south of Mahagi west of Lake Albert to the north of Fashoda to Belgium. The treaty was valid as long as King Leopold II remained in power.

According to the third article, Belgium ceded a 25 kilometer area from the northern port of Lake Tanganyika to the southernmost point of Lake Edward to England. The fourth article stated that no political rights were recognized in the leased territories, while the fifth article allowed the Congo Free State to construct a telegraph line between England’s colonies in South Africa and the Nile Valley. The sixth article emphasized that both parties would grant equal rights to their subjects in the leased territories.

On the day the treaty was signed, the British ambassador in Brussels sent a note to the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs requesting that the rights of the Ottoman Empire and the Khedive of Egypt over the Upper Nile Valley be considered. The Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs accepted this request.

After the signing of the treaty, England committed to advising the Secretary of State for the Colonies in West Africa to take necessary military measures for the rapid occupation of the territory ceded to Belgium.

The Ottoman Empire carefully monitored the situation after the treaty was signed. The Ottoman Empire argued that the treaty harmed the rights of the Khedive of Egypt and thus deemed the treaty invalid. The Ottoman Empire protested that the treaties between England and Belgium were invalid and that Ottoman rights in the region should be protected. During this period, the Ottoman Empire sent official notes to England and Belgium, questioning the legal validity of the treaty. Additionally, the Ottoman Empire stated that geographical surveys and explorations were necessary to protect its rights over the Nile Valley.

As a result, the Ottoman Empire pursued a cautious policy against the treaty and protested England’s occupation of the Vadelay and the treaty with Belgium. Sultan Abdulhamid II informed England that the region belonged to the Khedive of Egypt and conveyed his views to the British Foreign Secretary Lord Kimberley through Ambassador Rustem Pasha in London.

Upon the Congo’s advance toward Sudan, Sultan Abdulhamid II, in his will issued on April 10, ordered that the Belgian government should protest and measures should be taken against the idea of annexation without waiting any longer. He also advised the grand vizier to consult with the French ambassador in Istanbul since it was understood that the French government would support the Ottoman Empire in this matter.

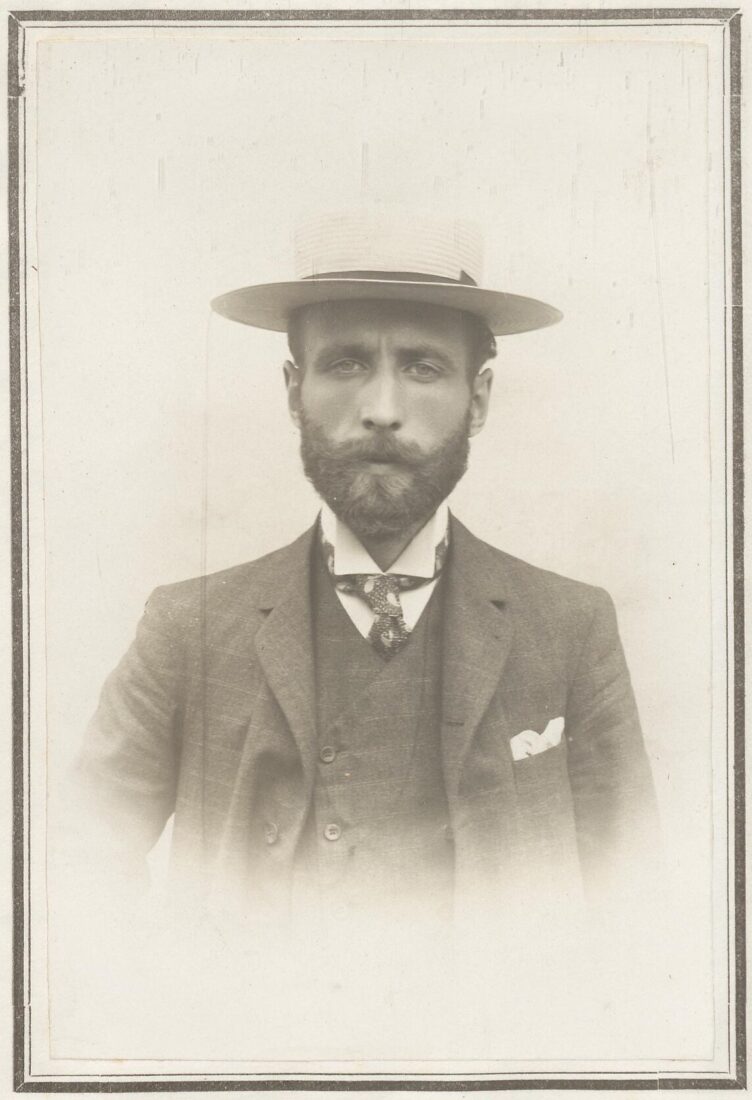

Belgian Edward Jorris, subcontracted Armenian organizations attempt assassination against Sultan Abdulhamid II

During a period of tensions between Belgium and Ottoman in Africa, Armenians, having failed to achieve results from their actions in 1895 and 1896, aimed to weaken the Ottoman Empire by carrying out an assassination of Sultan Abdulhamid II and orchestrating large-scale actions.

In January 1904, the Dashnak Congress held in Sofia decided to intensify actions in Istanbul and Izmir. According to the plans, an assassination would be carried out against the Sultan, followed by the bombing of the government center, Galata Bridge, Tunel, Ottoman Bank, foreign embassies, and other establishments. The goal was to create major chaos and revolution in Istanbul to provoke European intervention.

The assassination preparations were carried out by Russian Armenians Samuel Fain, his daughter Robina Fain, and Lipa Rips, in collaboration with Belgian anarchist Edward Jorris. The attack was scheduled for July 21, 1905 at Yildiz Mosque. However, the Sultan stayed a bit longer in the mosque after prayers, which disrupted the timing of the bomb and failed the assassination attempt. Many people around the area were killed or injured in the explosion.

Following the incident, an official announcement was made, and it drew significant reactions. The diplomatic crisis escalated when Belgium demanded the extradition of Jorris in response to accusations and claims against the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman government rejected the request, stating that the 1838 agreement did not grant such a right to Belgium. The Belgian government argued that the capitulations were being expanded and applied. This legal battle created a crisis that affected diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Ottoman Empire’s strategic diplomacy in changing world

During this period, the Ottoman Empire was no longer capable of deploying its military strength or intervening to protect its distant borders. Consequently, it had to base its foreign policy on the support of European states and focus solely on preserving its legal status.

However, driven by concerns about setting precedents, the Ottoman Empire remained vigilant, never relinquishing its claims or abandoning its efforts to secure rights even in regions far from the center.

It continuously assessed every piece of information and verified news from various sources to avoid taking steps detrimental to its interests. In defending its administrative rights in these regions, the Ottoman Empire argued that the Muslims living there could not be left under a Christian administration.

Additionally, as the Caliph of Muslims, Sultan Abdulhamid II sought to leverage his caliphate policy. His close attention to events in South Sudan demonstrates the Ottoman Empire’s cautious foreign policy approach and its intention to exploit every opportunity that could benefit it.