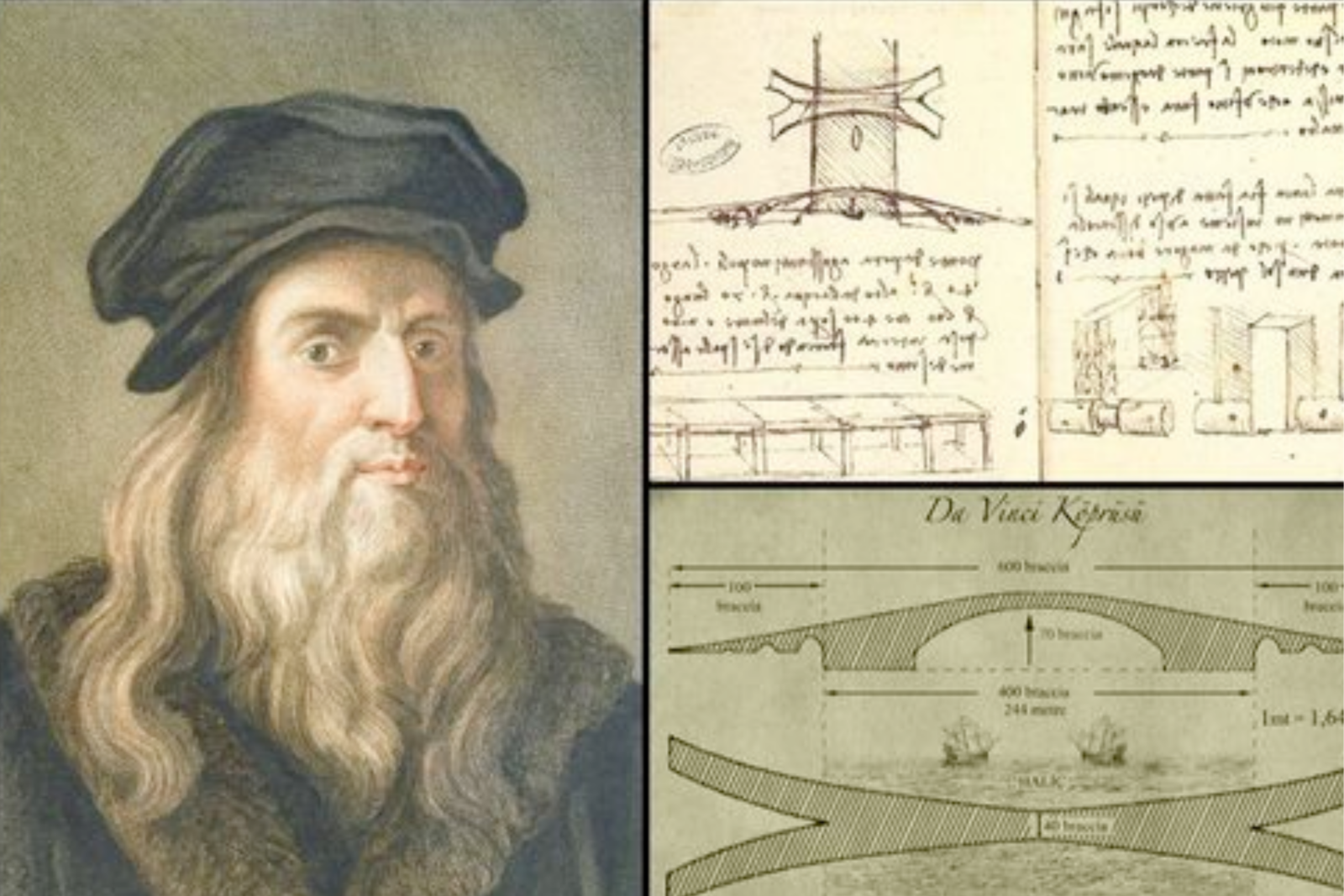

Leonardo da Vinci meets Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II: Istanbul’s unrealized Golden Horn bridge

How Da Vinci’s bold proposal to Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II could have changed Istanbul forever. (Created with Canva)

How Da Vinci’s bold proposal to Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II could have changed Istanbul forever. (Created with Canva)

Throughout history, many individuals have made contributions that they believed would change the world. Some were artists, others explorers, and others soldiers – Leonardo da Vinci was one of them.

Although there are limited documents and sources on the specific topic of his connection with the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid, we will explore this event based on the available information.

Notably, Da Vinci once wrote a letter to Sultan Bayezid II, proposing an ambitious design for a bridge over the Golden Horn in Istanbul.

Who really was Leonardo Da Vinci?

It is often said that great genius comes from hardship. Leonardo da Vinci’s difficult childhood played a significant role in shaping his exceptional abilities.

Born on April 15, 1452, in the village of Anchiano near Florence, in the Tuscany region, Leonardo was the illegitimate son of Ser Piero, a notary, and Caterina, a peasant woman. His parents married other people shortly after his birth – his father to a noblewoman, and his mother to a farmer.

Leonardo spent much of his early life with his father, who married three more times after his wife’s death. Despite growing up in his father’s household, Leonardo never received the affection he craved.

Being born out of wedlock was a significant stigma in Europe at the time, and as a result, Leonardo’s birth was kept hidden, and he faced societal shame. His status also prevented him from attending university, so he received an education through private lessons instead.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s hands-on education

In 1465, at the age of 13, his father, Ser Piero, sent Leonardo da Vinci to train under Andrea del Verrocchio, a renowned Florentine goldsmith. This decision marked a turning point in Leonardo’s life, leading him away from his father’s home and into an environment where his artistic and intellectual talents could flourish.

Verrocchio was more than a goldsmith; he was also a painter, sculptor, architect, and mechanic. Under his mentorship, Leonardo developed skills in various fields, including geometry for architecture, carpentry, and bronze casting.

This diverse education laid the foundation for da Vinci’s later accomplishments in art, engineering, and mechanics – fields in which he would one day propose an innovative bridge design to Sultan Bayezid II.

Leonardo spent his formative years in Florence, a city that nurtured his burgeoning genius. Surrounded by influential figures and exposed to new ideas, he honed his talents. By 1472, his abilities were recognized when he was accepted as a master into the prestigious Compani di San Luca, an association of leading Florentine painters.

Despite this achievement, he continued to work closely with Verrocchio until 1476, benefiting from his guidance.

In 1482, Leonardo entered the service of Lodovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan, further boosting his reputation. Although he was now working for the Duke, Leonardo still maintained ties to Florence.

During this time, his reputation as a multifaceted genius grew, setting the stage for his later contributions to engineering, including his Golden Horn bridge proposal for Istanbul.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s great struggles in Florence, Milan

During his time in Florence, Leonardo continued to expand his knowledge and skills. While his early works were mainly in drawing and sculpture, he also created paintings that would later define his legacy.

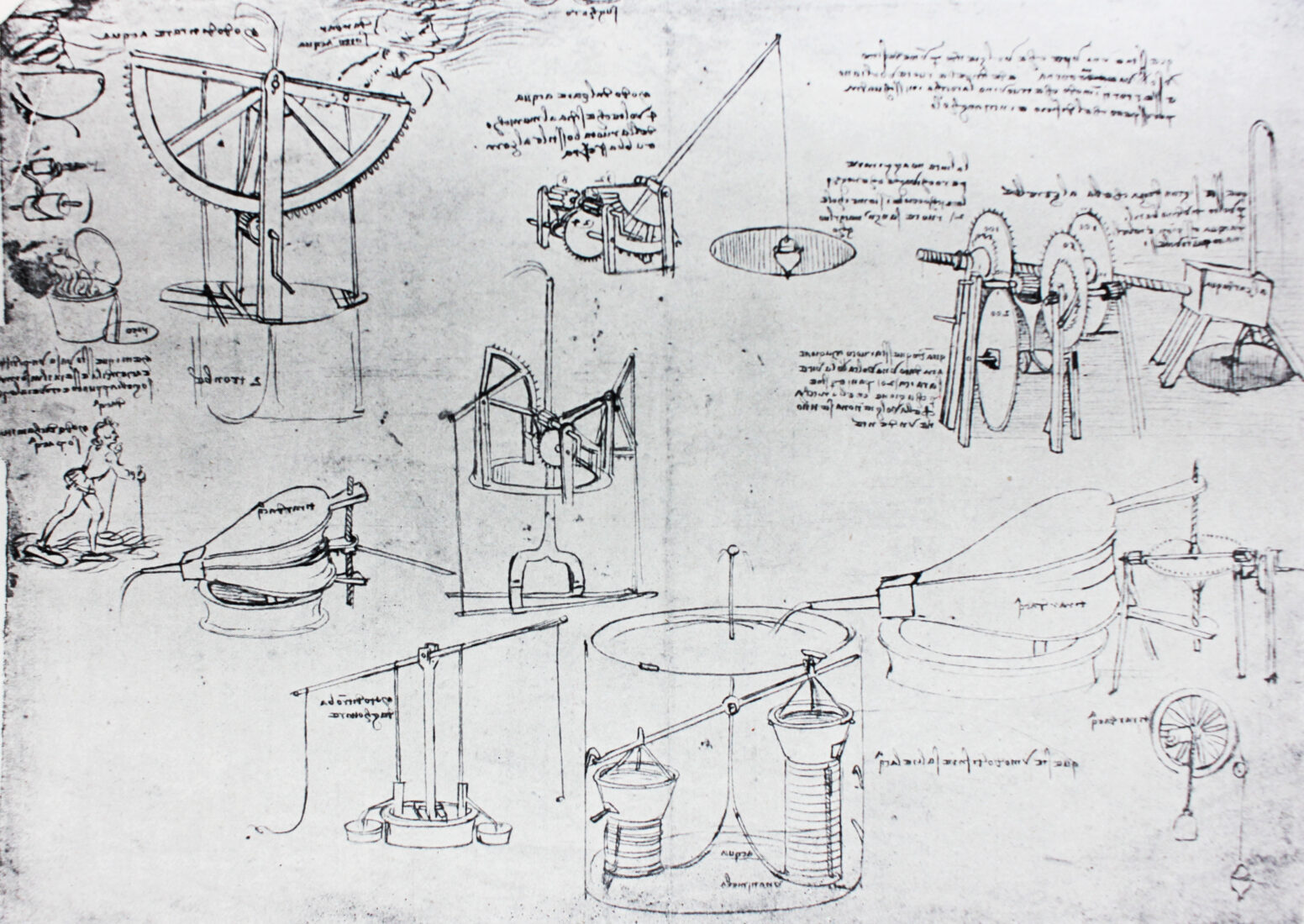

His curiosity, however, extended beyond the realm of art – he became deeply interested in engineering and architecture. For example, he considered practical problems such as how to travel from Florence to Pisa along the Arno River and how to harness waterpower for various applications.

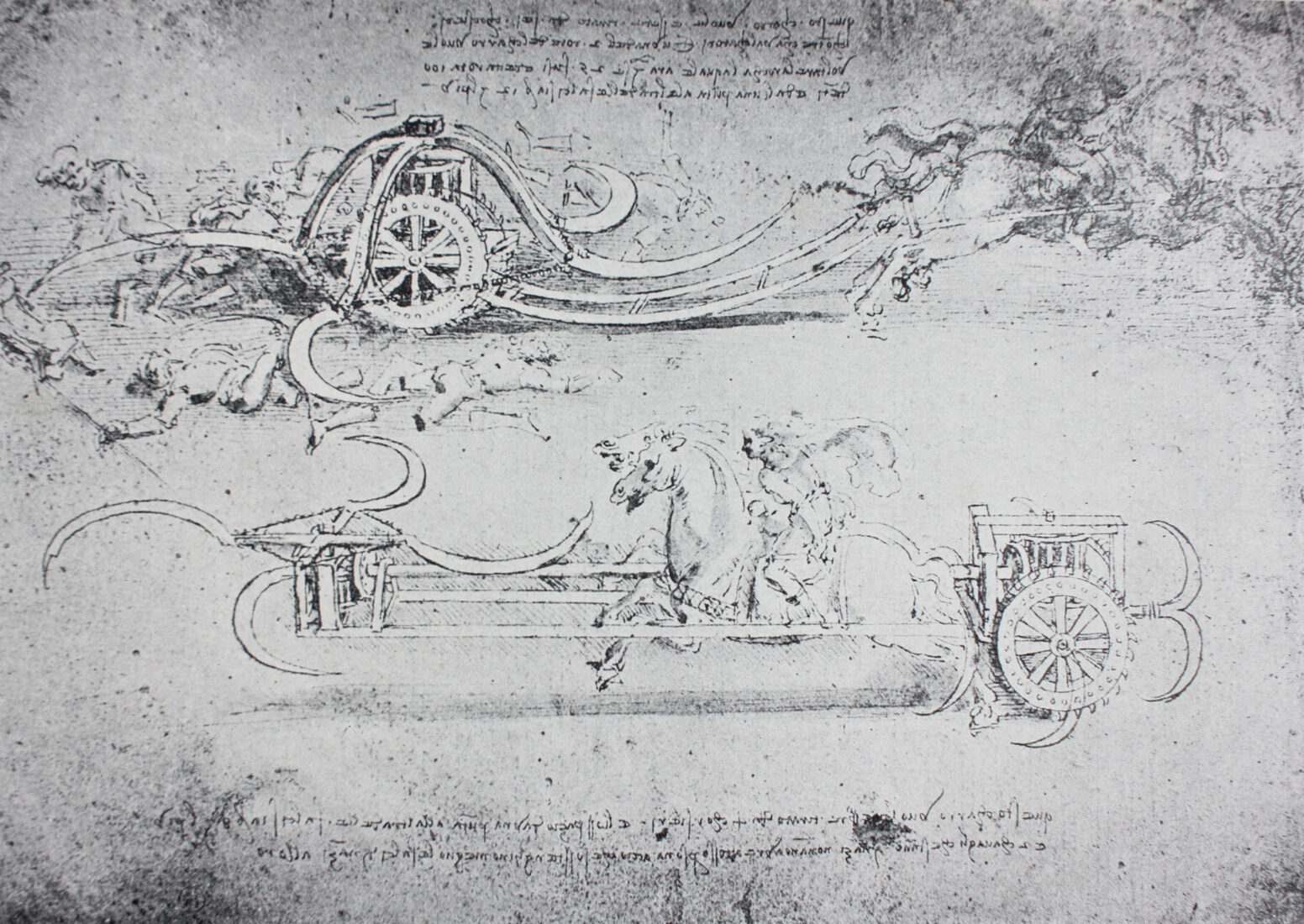

Besides these civil engineering ideas, Leonardo delved into military technology. In a letter to the Duke of Milan, Lodovico Sforza, in 1488, he detailed several techniques for warfare. He described how to drain trenches during sieges, how to construct various types of bridges, how to conceal roads and stairways, and how to design machines for battle.

Leonardo’s genius was apparent in these plans, yet he expressed frustration at having to rely on his engineering skills for survival rather than his art. In his letter, it is clear that he felt unrecognized for his true potential as an artist and inventor.

Despite this, Duke Sforza, also known as the ‘Tyrant of Milan,’ valued Leonardo’s abilities, particularly as an engineer during wartime, and provided him with financial support.

However, when the Duke was defeated by the French in 1499 and captured by Louis XII, Leonardo fled to Venice with his friend Luca Pacioli. Following this upheaval, Leonardo sought new patrons to support his increasingly ambitious projects. Under the protection of Giuliano de Medici, he later moved to Rome with his student Francesco Melzi, where he continued to propose bold new ideas.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s visionary proposal to Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II

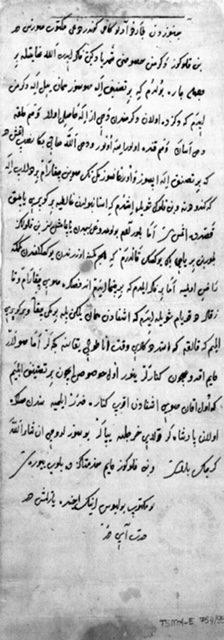

The focus of this article is Leonardo da Vinci’s letter to Ottoman Sultan Bayezid, in which he proposed one of his ambitious projects.

This letter, preserved in the Topkapi Palace archives, demonstrates Leonardo’s awareness of Bayezid II’s desire to build a bridge over the Golden Horn. In it, Leonardo promised he could realize the Sultan’s vision. Below is a translated excerpt from the letter.

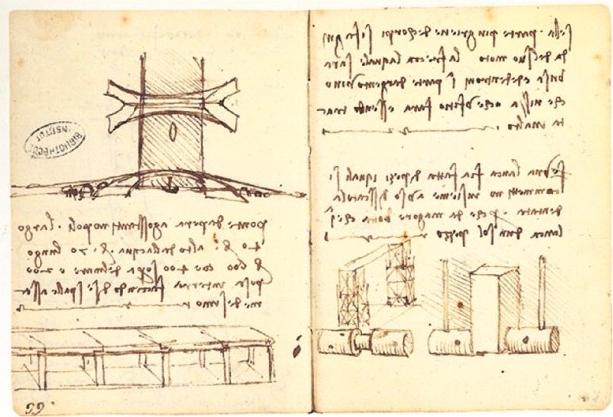

This is a letter from an infidel named Leonardo the Genoese. With God’s help, I have considered an idea for the mill you desire your servant to build. Let me construct a wind-powered mill that does not require pressurized water, consuming less energy than those used at sea, thereby making the people’s work easier.

I also heard of your wish to build a bridge for Galata. However, it has not been realized due to the lack of a capable builder. I, your servant, know how to accomplish this. If a bridge is built too high, people will be reluctant to cross it. Yet, I have devised a way to construct a bridge that will allow ships to pass underneath with ease, while also providing a convenient crossing to the Anatolian side for your people.

On occasions when the water rises, even the bridge’s supports may erode, but I have a solution for that, ensuring future sultans can manage it effortlessly. May you accept my words as truthful, and I remain ever at your service.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s letter to Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II

Now, let’s consider the interpretation of the document. The first important aspect is the language in which the letter was written. There is some debate over whether the letter was originally composed in Italian or Turkish.

Did Leonardo Da Vinci write to the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid in Turkish?

Typically, foreign letters in the Ottoman archives include phrases like “it is translated in the form” or “it is translated from this language,” indicating that they had been translated from another language.

However, this specific phrase is absent from Leonardo’s letter, leading to speculation that the letter might have been written in Turkish.

How likely is this possibility? Given the strong commercial ties between the Ottoman Empire and the Italian city-states, particularly Genoa, it is plausible. Over time, Italian merchants became proficient in Turkish to communicate with high-ranking officials.

From this perspective, it is conceivable that Leonardo’s letter regarding his Golden Horn bridge idea was written with the help of an Italian merchant who was fluent in Turkish.

That said, the alternative possibility cannot be dismissed – that the letter was originally composed in Italian and later translated at the palace. The Ottoman court employed skilled translators for diplomatic correspondence, and it is well documented that they handled many such translations for the Imperial Council.

Ottoman Imperial Council’s official translators

Since its establishment, the Imperial Council employed translators to manage the state’s correspondence with foreign rulers. The reign of Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II was a significant period in the development of this institution. During Bayezid’s time, the translation services of the Imperial Council became more structured and systematic.

Archival records from this era provide a detailed look into this process, including a notebook from 1503 to 1527 that offers valuable insights into the translators or “dragomans,” who served the council during Bayezid II’s reign.

According to this notebook, three translators are listed under the title “Sakirdan-i Katiban-i Hizane-i Amire” as authorized staff of the council: Alaaddin, Alexander and Ibrahim. Another prominent figure was Ali Bey, a famous translator who appeared in records for the first time on January 11, 1507, though he had already been appointed as the council’s translator in 1502.

Ali Bey’s proficiency in foreign languages made him a valuable asset, and he was sent to Venice as an ambassador on multiple occasions – once during the reign of Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II and again under Yavuz Sultan Selim.

From these records, it becomes evident that the Imperial Council had a well-established system of qualified translators to handle foreign texts. Given this information, it seems more likely that Leonardo’s letter was originally written in Italian and translated to the palace, although the possibility of it being written in Turkish cannot be entirely ruled out.

Did Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II contact Da Vinci about Golden Horn bridge?

Another claim regarding the letter suggests that Da Vinci wrote it in response to an order from Sultan Bayezid II to design a Golden Horn bridge. However, there is no evidence in the state archives supporting the idea that the Sultan directly commissioned Leonardo for this project.

Instead, Leonardo’s own words in the letter indicate that it was his initiative. In the letter, he writes, “I, your servant, heard that you intend to build a bridge from Istanbul to Galata,” implying that the Golden Horn Bridge project was not requested by Bayezid II but rather proposed by Da Vinci himself.

When did Leonardo Da Vinci send letter to the Ottoman Sultan?

The date of the letter is also a point of discussion. The text includes a note stating that it was written “on the third of the month of Yulyus,” referring only to the month and day. While some claim that the letter was written in 1503, archival records list the date as 918 Hijri, which corresponds to 1512. This timing offers insight into why Bayezid II may have been indifferent to Leonardo’s bridge proposal.

By 1512, the Ottoman Empire was facing increasing internal and external challenges, including rising Kizilbas activity in Anatolia and escalating tensions between Bayezid’s sons over succession. Given these circumstances, it is not surprising that the Sultan did not prioritize Leonardo’s Golden Horn bridge proposal.

The transition of power from Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II to his son, Selim I, and the growing Safavid threat shifted the Empire’s focus to more pressing political concerns. As a result, Da Vinci’s ambitious project was shelved and never realized in Istanbul.

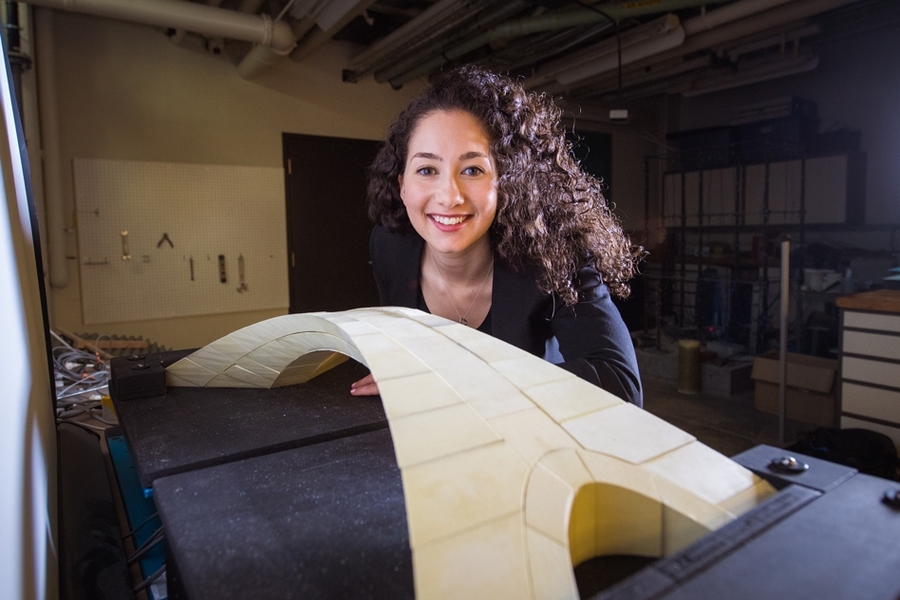

However, nearly 500 years later, in 1996, Norwegian architect Vebjørn Sand revived Leonardo’s Golden Horn bridge design. With approval from the Norwegian government, Sand constructed a bridge based on Da Vinci’s plans, connecting Oslo to Stockholm.

The bridge, named the “Leonardo Da Vinci Bridge,” was officially opened to the public on October 31, 2001.