Late Ottoman Empire: Commentaries on women in public

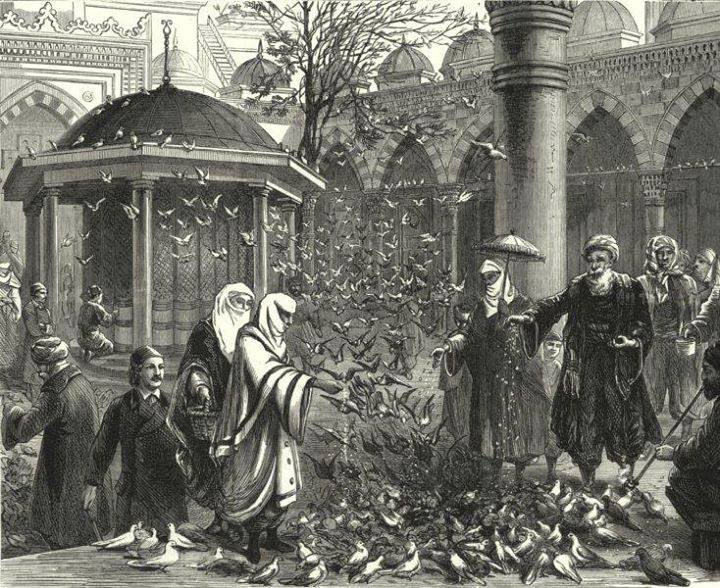

View of Ottoman Istanbul in late 1800s. Image published by Reinhold Publishing House in Berlin in 1890. (Austrian State Archive).

View of Ottoman Istanbul in late 1800s. Image published by Reinhold Publishing House in Berlin in 1890. (Austrian State Archive).

In the 19th century, women also began strolling the streets during Ramadan more comfortably. In later periods, they also began attending performances like theater and improvisational shows. According to Melek Hanim, wife of Grand Vizier Kibrisli Mehmet Pasha, Ottoman women, who did not go out except for special occasions, went out for walks in the evenings during the month of Ramadan and did not return until midnight. Husbands did not dare prevent their wives from going to the mosque or a friend’s place with an elderly slave unless they risked being ridiculed.

Beyazit Square, Sehzadebasi, and later Beyoglu were districts frequented by women during Ramadan. While Sehzadebasi was a popular place due to the abundance of entertainment venues during Ramadan, Beyazit Square was a favorite spot for women taking evening walks due to its spaciousness. Namik Kemal, in an article published in the newspaper Tasvir-i Efkar in 1867, reported about women going to Beyazit during Ramadan for the last 20-30 years. Therefore, we can say that these walks started approximately during the Tanzimat period.

In the 1860s, Hristo Stambolski, a Bulgarian-born student of Mekteb-i Tibbiye, described the events in Beyazit Square during Ramadan as follows: “Beyazit Square was the favorite place for the upper-class Turkish society for afternoon strollers during Ramadan and holidays. Pashas, noblemen, and gentlemen from the Turkish aristocracy, riding well-groomed horses, and their harems, wearing magnificent silk and velvet blouses and feraces, and covering their heads with thin, very transparent veils, came here, hidden in rich and beautiful carriages.

A large number of carriages, in which the ladies of the palace were seated, lined up here as if they had come to a parade. The ladies of the palace, who thought they were entitled to everything, threw oranges, bonbons, and gold coins to the students of Mekteb-i Tibbiye, who were called “green-headed” because of the clothes they wore, accompanied by sighs of love. These sighs brought the women to their senses.”

During Ramadan and on holy nights (kandil), women gathering in Beyazıt Square, much like men, in a market-like atmosphere was a frequent topic in the Ottoman press at the time.

Namik Kemal, among the people who were uncomfortable with the Beyazit walks, said: “A group of delicate ladies, with their carriages, come to the square, singing the song of a thousand admirers, and flirt with the surroundings more than the men. The men and women who walk around here are not well-mannered. The evils seen here do not occur even in the freest places of the freest countries. The situation of the women who walk in these channels is certainly more inappropriate than that of European madams. The fact is that women are not veiled in Europe, but a man cannot even address the lowest prostitute on the street. Here, however, everyone can say whatever they want to a woman they do not know at all, as if she were a 50-year-old confidante. Some of the ladies do not hesitate to condone these treatments as a harmless entertainment.”

In Terakki Newspaper, the fact that going to Beyazit Square during Ramadan and kandil nights was almost an absolute necessity for some women was criticized: “Seeing the state of those who left their work, food, and spouses in frosty weather to go there for entertainment, and especially seeing the poor women walking on foot, and the fools who pretend to be wise but are ignorant of the world, and the foolishness that imitates them, and the unemployed and powerless others standing on their feet in the mud and on the sidewalk, shivering, and the gentlemen and aghas who grab their canes, put on their glasses, leave their shops, look around in confusion, and drool in bewilderment, makes one feel sorry. Good sir! What can we do, should we put a stove in Bayazit Square?”

A critical article published in Ibret during Namik Kemal’s tenure as the chief editor for a period, discussed women’s Beyazit walks. It stated that while it is understandable that everyone cannot be prevented from walking in the streets, it is incomprehensible that it is tolerated on such days while the mingling of scantily clad women in carriages and on foot with men of various nationalities is prevented at other times. Similarly, a letter from an elderly woman, published in Ibret, expressed her astonishment at what she witnessed in Sehzadebasi. The letter included the following remarks:

“Times have become so bad! Good and evil have become indistinguishable. But all these evils are caused by women. I have nothing to say to men! After those sluts dress up like that, put on wigs made of the hair of dead cockroaches on their heads, and wear boots on their feet and dresses on their backs, and go out to places like the market and Beyazit, of course, men will not leave them alone.”

Similar criticisms regarding women’s attire frequently appeared in other newspapers of the period, sometimes in humorous tones, and sometimes with heavy accusations. For example, in Diyojen, a satirical magazine, women’s practice of having special Ramadan clothes tailored, adorning themselves, and viewing this period as an opportunity to freely roam and socialize was often criticized.

In another issue of Diyojen, there is news of women being banned from going to Beyazit. However, it is stated that this ban is only for those who are scantily clad, wear feraces with collars falling off their shoulders, shorten their skirts to show off their cotton knee socks, and tilt their umbrellas to one side.

In the Caylak magazine, the transparency of women’s veils is emphasized with the phrase, “A yard of fine tulle for medicine cannot be found at the head of the Kalpakcilar!” Criticism of inappropriate attire and behavior during Ramadan outings was not limited to women; men also faced their share of scrutiny. For instance, Caylak magazine criticizes men who sit on stools in front of coffeehouses and casinos from Laleli to Aksaray after one o’clock (1 p.m.), making clownish gestures with flowers in their hands to attract women.

In the conservative Ottoman society, it is expected that these relatively relaxed behaviors of women during Ramadan would lead to some familial problems, but records on this subject in the press and memoirs are extremely rare. Ahmet Mithat, in the Tercuman-i Hakikat newspaper, mentions that with the arrival of Ramadan, the impropriety of some women’s actions in places like Beyoglu and Kagithane began to be discussed. Instead of the severe punishment methods (cutting and dismembering, eliminating bodies) in a harsh document sent to the newspaper on this matter, Ahmet Mithat suggests that this inappropriate situation should be reported to a male guardian of the women, such as their husbands, fathers, or elder brothers.

However, he noted that if a husband is aware of his wife’s actions and chooses not to intervene, nothing can be done except to say, “May God curse both the woman and the man!” In response to the suggestion of entrusting women’s reform to the police, Ahmet Mithat argues that the police already have the authority to intervene in cases of improper conduct. However, he warns that granting them additional powers could lead to negative consequences. He recalls an incident from the previous year when several detained women fainted, noting that these women were, in fact, respectable individuals. As a result, Ahmet Mithat argues that ensuring the reform of women’s morals is the duty of the men in their families.

Although it is difficult to estimate the proportion of women who made it a habit to go out during Ramadan in Ottoman Istanbul, it is possible to understand that it was not insignificant from the frequency of the warnings made by the government on this matter. The most important measure taken by the government to restrict or even prevent women’s Ramadan outings was the issuance of various edicts at different times. These edicts warned against women stopping their carriages in the middle of the streets in Beyazit and Sehzadebasi, wearing religiously inappropriate clothing in bazaars and markets, and men harassing women by loitering among the carriages.

It is understood from the news published in the press that these warnings made by the government could maintain their validity for a certain period but then gradually loosened over time. For example, in a 1900 article titled “Ramadan Markets” signed by Mustafa Asim in the “Ladies’ Newspaper,” it is alleged that despite the warnings issued in a sultan’s order published in newspapers against women wearing clothes that were not in accordance with Islam and wandering around, some women used Ramadan to go out with tight charshafs with waist-tightening capes and thin veils, wearing mother-of-pearl prayer beads over gloves.

It is stated that if the weather was suitable, women would go to the mosque before the afternoon and pray, then pour into the market streets, and on Fridays and Sundays, they would not even pray and join the carriage market, wandering until five or ten minutes before the iftar cannon. Similarly, in Sura-yi Ummet in 1903, it is stated that during Ramadan, which should be spent engaged in worship, some Muslim women made a carriage market in Direklerarasi and some foolish people indecently harassed these women. It is announced that Sefik Pasha, the Zaptiye minister of the period, issued an order to completely abolish the Ramadan market due to this situation contrary to Islam, to punish the carriage drivers who acted otherwise, and to warn the owners of the mansion carriages by learning who they were.

The month of Ramadan is not only interesting in terms of the relative ease seen in women’s behavior as a result of the freedom they gained compared to other months of the year. The plays staged in Karagoz (shadow puppetry), Orta Oyunu (traditional Turkish theater), and theaters during this month also create a contrasting situation with the environment, sometimes due to their potentially immoral aspects. Most plays, which had limited performance opportunities outside of private home invitations or naval festivities, were specifically staged during Ramadan.

Ottomans, who sometimes took their children to these shows, did not seem to be very disturbed by some of the indecent words of Karagoz or the play “The Rake Raid” by theater actors, keeping in mind that it was the month of Ramadan. The same tolerance extended to those who spent the night watching foreign women dance.

In this regard, Ramadan in the Ottoman period was a time of festive freedom rather than religious fanaticism. The state granted Muslims the freedom to enjoy themselves freely during this month, just as it granted non-Muslims the same freedom during the Carnival and Easter periods. The Muslim community took full advantage of this freedom of entertainment, which they saw as a natural right.