How Santorini’s volcanic catastrophe shaped Türkiye’s ancient cities

The underwater caldera of the Santorini volcano, photographed from the International Space Station. The central lagoon is surrounded by several islands, including the largest, Santorini. (Photo via NASA; Photo collage by Koray Erdogan/Türkiye Today)

The underwater caldera of the Santorini volcano, photographed from the International Space Station. The central lagoon is surrounded by several islands, including the largest, Santorini. (Photo via NASA; Photo collage by Koray Erdogan/Türkiye Today)

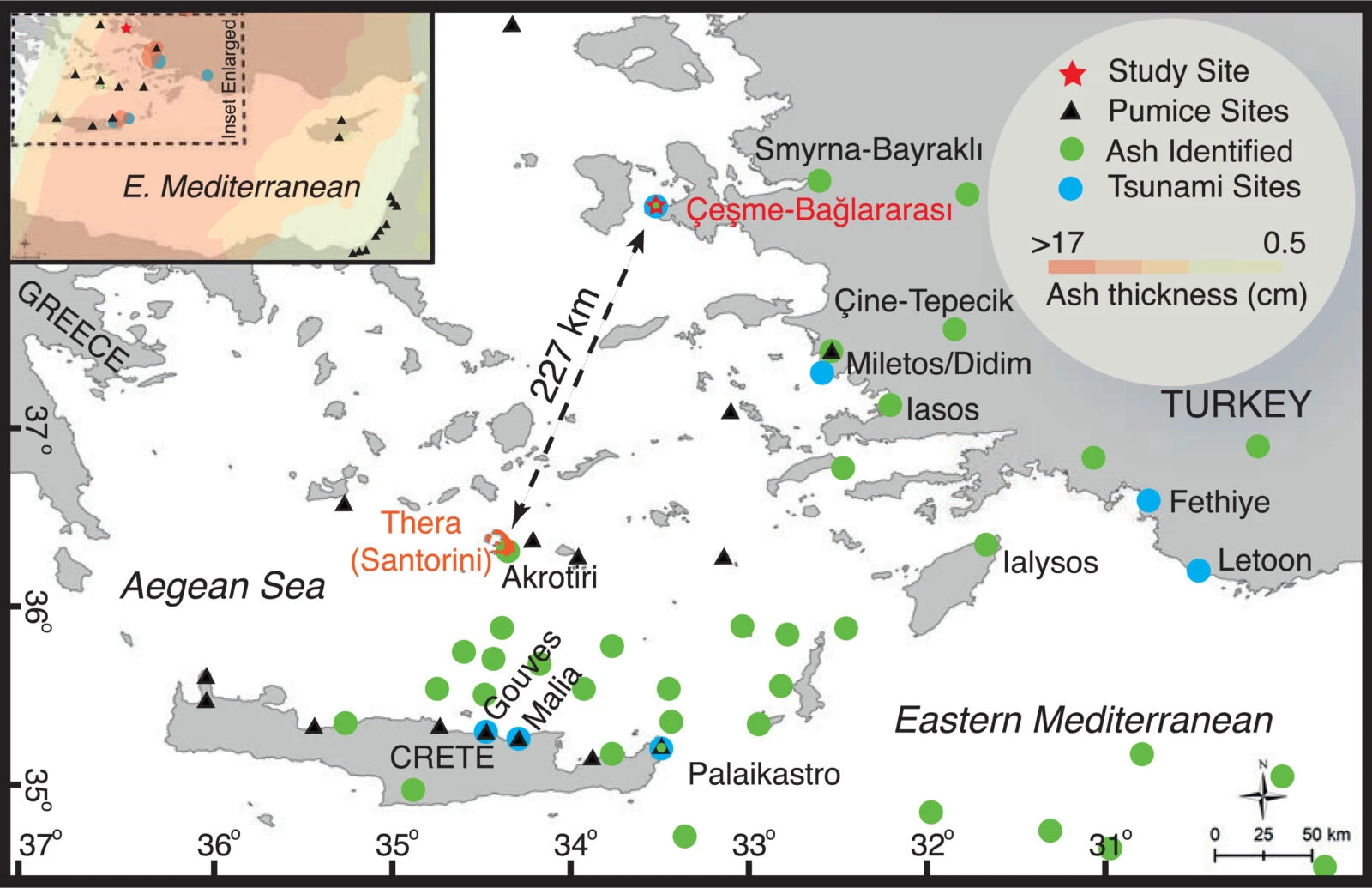

The catastrophic eruption of Santorini 3,500 years ago was one of the most powerful volcanic events in human history, leaving a lasting mark across the Mediterranean.

Recent archaeological discoveries in modern-day Türkiye have uncovered layers of volcanic ash, shedding light on the disaster’s far-reaching consequences.

From the ancient city of Tepecik Hoyuk to the Lycian capital of Patara, evidence of Santorini’s eruption continues to emerge, revealing the scale of the catastrophe.

How did Santorini eruption affect Anatolia?

Archaeologists have identified multiple sites across Türkiye that bear clear traces of volcanic ash and tsunami deposits caused by the Santorini eruption. These discoveries raise several intriguing questions:

- How did the eruption impact trade and agriculture in the region?

- Did the tsunami triggered by the eruption reach the Aegean coastline?

- Could environmental changes caused by the disaster have influenced political shifts in ancient Anatolia?

Let’s explore the key archaeological sites that reveal the Santorini eruption’s devastating effects.

1. Tepecik Hoyuk: Ash layers reveal volcanic aftermath

Location: Cine district, Aydin

At Tepecik Hoyuk, a crucial Bronze Age settlement, archaeologists have uncovered thick layers of volcanic ash directly linked to the Santorini eruption. Professor Sevinc Gunel and her team discovered microscopic glass fragments typical of volcanic events, confirming that the site was exposed to the disaster.

Key findings:

- Volcanic ash deposits analyzed by the Technical University of Vienna match those from Santorini.

- The presence of glass shards suggests that the eruption’s ash cloud traveled far across the Aegean.

- The site’s excavation offers insights into how local populations may have responded to the catastrophe.

2. Patara: Lycian coast under volcanic ash

Location: Antalya province

Patara, the ancient capital of the Lycian League, also bears evidence of Santorini’s eruption. Professor Havva Iskan Isik and her team have identified a layer of volcanic ash covering portions of the site.

Did a tsunami reach Patara?

While no direct signs of a tsunami have been found, the widespread presence of volcanic debris suggests that the eruption’s atmospheric effects extended across the Mediterranean.

Key findings:

- A visible layer of ash confirms the presence of volcanic activity.

- The discovery raises new questions about how Lycian cities were affected by sudden climate shifts.

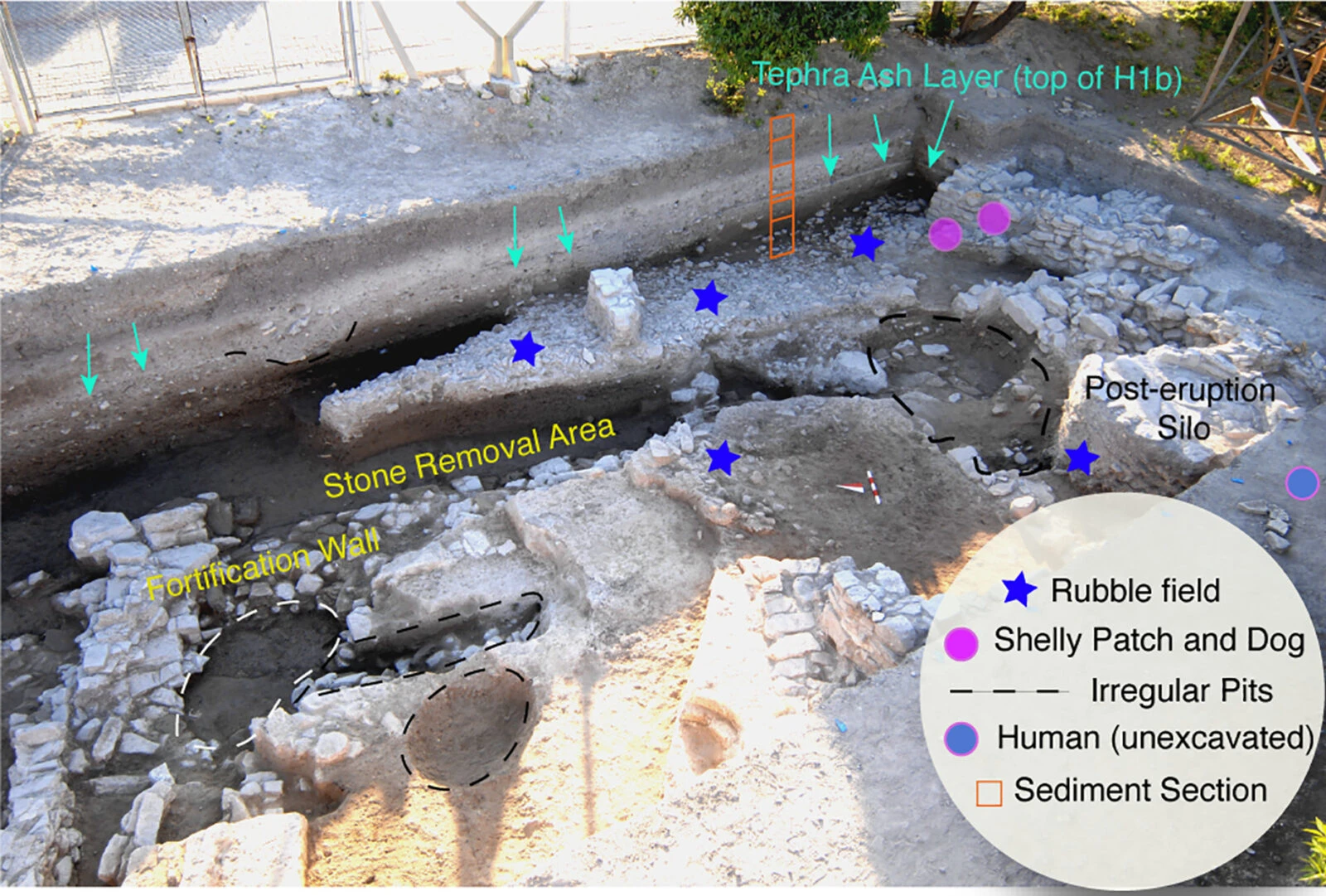

3. Cesme-Baglararasi: First direct evidence of tsunami

Location: Cesme, Izmir province

Perhaps the most striking discovery comes from Cesme-Baglararasi, where archaeologists have uncovered the first direct evidence of a tsunami triggered by the Santorini eruption. Excavations between 2009 and 2019, led by Professor Vasif Sahoglu, revealed human remains and debris embedded in tsunami deposits.

How destructive was tsunami?

- The tsunami is considered one of the most powerful natural disasters in Mediterranean history.

- Human remains found at the site suggest victims were caught in the waves.

- Layers of marine sediments indicate strong flooding reached the Anatolian coastline.

4. Sardis: Lydian Kingdom’s volcanic connection

Location: Manisa province

Sardis, the capital of the ancient Lydian kingdom, has also yielded traces of volcanic tephra from the Santorini eruption. The discovery suggests that environmental disruptions, including crop failures and famine, may have influenced the region’s socio-political changes.

Key findings:

- Volcanic ash deposits may explain documented periods of agricultural decline.

- Some historians believe famine caused by the eruption could be reflected in Lydian myths.

- The event’s long-term consequences might have played a role in shaping early Greek narratives.

5. Iasos: City buried under volcanic ash

Location: Mugla province

The ancient city of Iasos was also heavily affected by the eruption. In 2013, archaeologists discovered a thick layer of volcanic ash that had buried parts of the settlement.

How did ash help preserve city?

Italian archaeologist Marcello Spanu suggests that the ash-covered structures in Iasos were preserved in a manner similar to Pompeii after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Key findings:

- Well-preserved ancient tunnels and a sewer system were found beneath the ash.

- The city’s architecture provides valuable insights into Bronze Age urban planning.

6. Miletus: Minos influence and volcanic impact

Location: Aydin province

Miletus, a major trade hub in the ancient world, also bears signs of Santorini’s volcanic disaster. Archaeological layers reveal a thick deposit of ash, hinting at environmental consequences that may have impacted the city’s development.

Key findings:

- Possible volcanic ash damage found in excavations.

- Evidence suggests the eruption influenced trade routes between Anatolia and Crete.

- The disaster may have contributed to shifts in Minoan and Anatolian interactions.

7. Smyrna: Evidence of volcanic fallout

Location: Izmir province

Recent drilling work at Old Smyrna has uncovered ash deposits from the Santorini eruption, confirming that the disaster impacted the Anatolian settlement.

Key findings:

- Ash samples collected at the site are being analyzed by the Geography Department of Ege University.

- The discovery helps archaeologists estimate the environmental consequences on the city’s culture and society.

- The findings contribute to a broader understanding of how the eruption affected the Mediterranean region.

8. Ayasuluk Hill: First evidence of Mycenaean settlement and ancient walls

Location: Selcuk, Izmir province

Ayasuluk Hill, located in the Selcuk district of Izmir, has revealed significant archaeological layers from the Bronze Age through to the Early Ottoman Period. Among the key discoveries are architectural remains constructed from materials brought in from Hellenistic and Roman Ephesus, which were repurposed in this region.

What’s significant about the findings?

A massive wall, 3 meters wide and made from rough stone, was discovered in the Middle Bronze Age layer. This is considered a part of the earliest defensive structures in the region. Additionally, a layer of ash found above the wall is believed to be linked to the volcanic eruption of Thera around 1,550 B.C.

What do findings suggest about the area’s history?

- The Mycenaean graves near the entrance gate indicate that Ayasuluk Hill may have hosted a fortress.

- The ash layer above the wall suggests a connection to the volcanic eruption of Thera around 1,550 B.C.

- The rise of the ash layer above the wall points to the potential presence of a Mycenaean castle and settlement.

- These discoveries highlight Ayasuluk Hill’s significance as an ancient site with defensive structures and early settlement activity.

Lasting impact of Santorini’s eruption on Türkiye’s ancient cities

The evidence uncovered across Anatolia highlights the far-reaching consequences of one of history’s most destructive volcanic eruptions. From tsunamis and crop failures to potential societal changes, the disaster likely played a role in shaping the course of ancient civilizations.

Key questions for future research:

- Did populations in Anatolia attempt to adapt to the environmental changes caused by the eruption?

- Could the Santorini disaster have triggered migrations or political shifts?

- How do these discoveries reshape our understanding of Bronze Age societies in the region?

As archaeologists continue to uncover new evidence, Santorini’s eruption remains a fascinating and complex chapter in the history of the Mediterranean.