How Germany nearly acquired Türkiye’s priceless artifacts in 1913

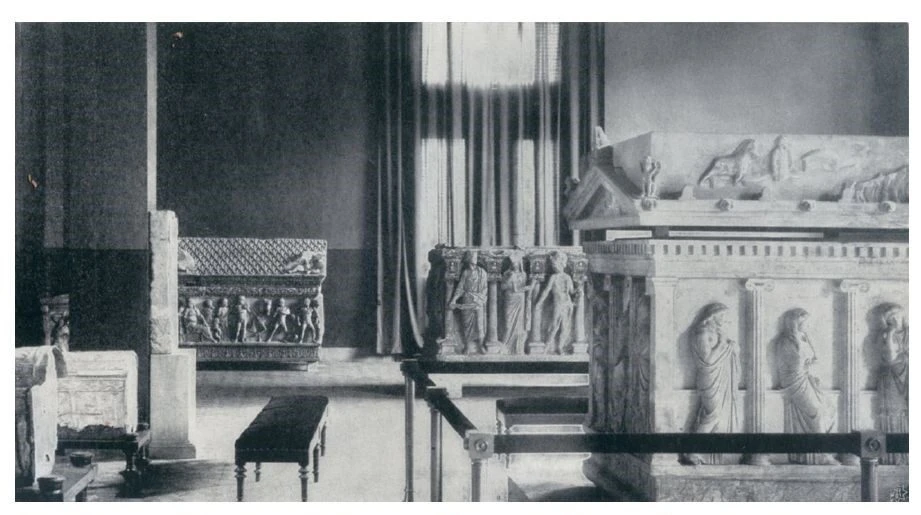

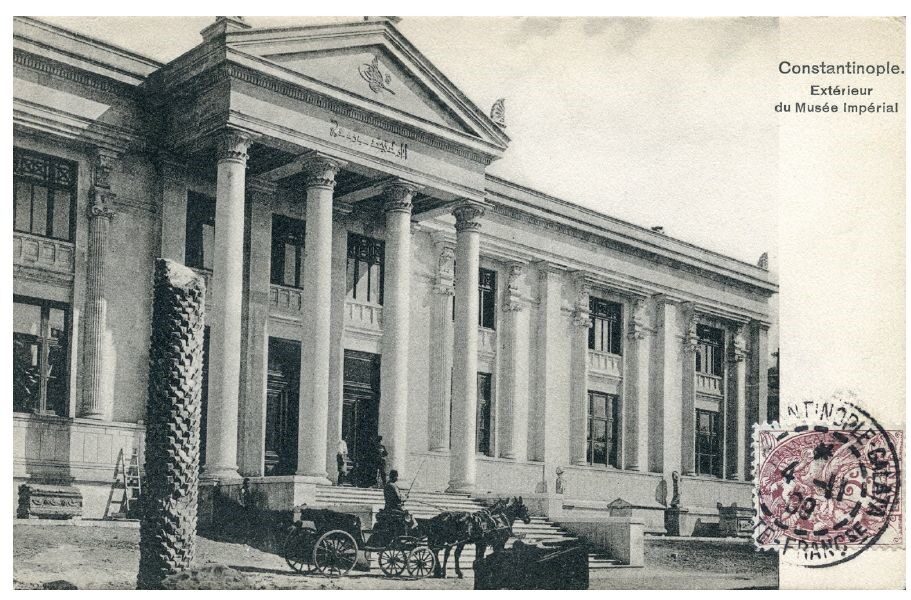

Room with the large sarcophagi in the Archaeological Museum, Istanbul, 1909 or shortly before (IHA Photo)

Room with the large sarcophagi in the Archaeological Museum, Istanbul, 1909 or shortly before (IHA Photo)

A new revelation has surfaced regarding Germany’s 1913 attempt to seize priceless artifacts from the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

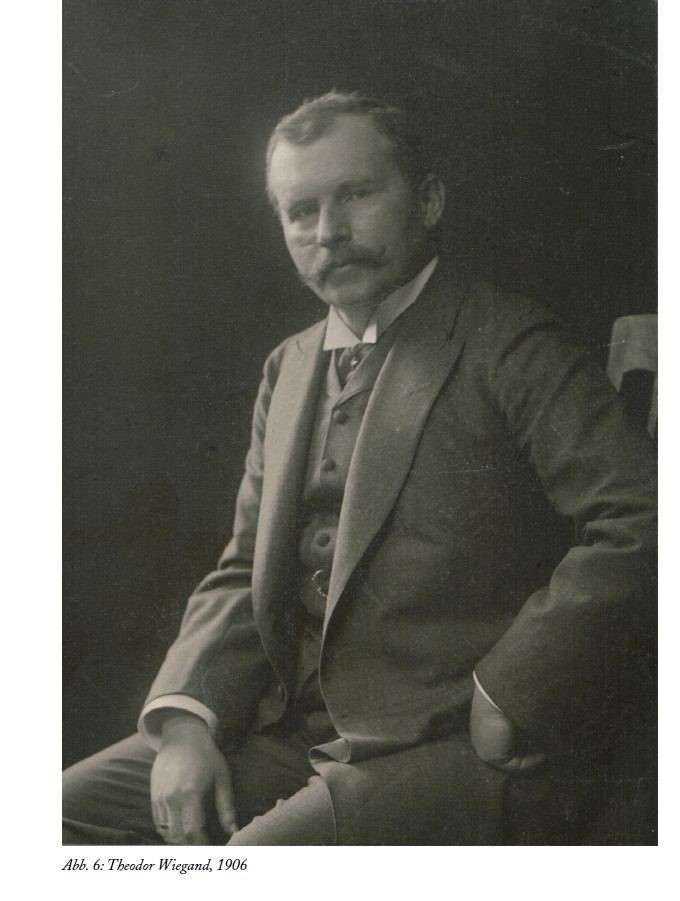

The plot, orchestrated by German archaeologist Theodor Wiegand, involved offering a substantial loan to the Ottoman Empire in return for some of the museum’s most valuable pieces. This proposal was made at a time when the empire was in deep financial distress.

Professor Nurettin Arslan, head of excavations at the ancient city Assos and faculty member at Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, unearthed this shocking scheme in his latest book “Assos-Behram”, which chronicles significant archaeological events from the Ottoman era.

Hidden museum deal

Arslan notes that Wiegand – who led excavations at Didyma, Priene and Milet – identified an opportunity in the economic troubles of the Ottoman Empire. He proposed using key artifacts from the Istanbul Archaeological Museum as collateral for a loan from the German Bank.

The plan was for the Ottomans to default on the loan, leading to the museum pieces being transferred first to the German Bank and then to the Prussian state.

“Theodor Wiegand suggested that the most important artifacts be used as security for a large loan to be granted to the Ottoman Government by the German Bank,” explained Arslan. “He believed it was inevitable that the Ottomans would be unable to repay the loan, and thus the artifacts would eventually belong to the Prussian state.”

German preparations for deal

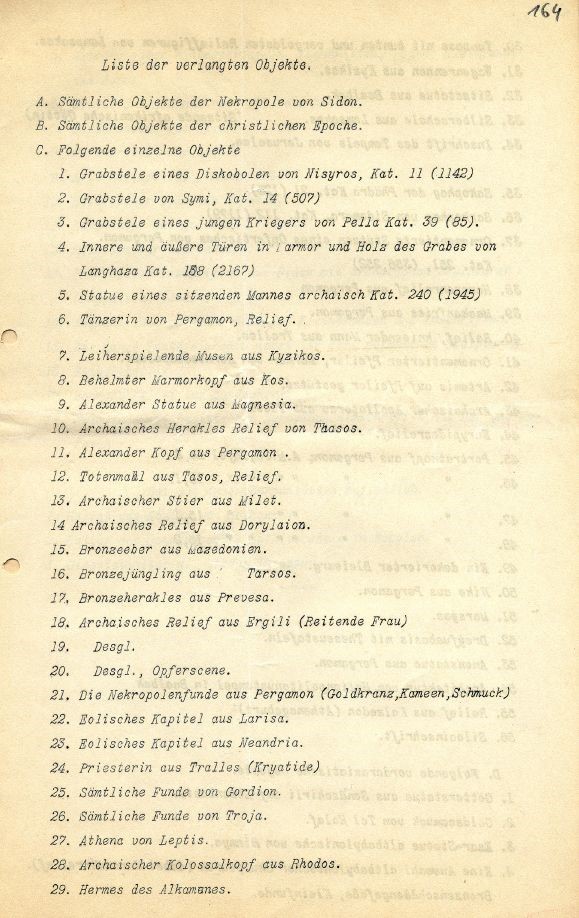

In July 1913, negotiations for this so-called “museum agreement” or “museum negotiations” began and continued until March 1914. The Germans were so confident that the Ottomans would sign the agreement that they had already prepared a list of which artifacts to take.

“Wiegand’s list included some of the most valuable items in the museum, such as the Alexander Sarcophagus, brought from Sidon by Osman Hamdi Bey, the most treasured sarcophagi and Trojan relics, as well as the Assos Athena Temple reliefs and a bronze plaque linked to Emperor Caligula,” said Arslan.

Fortunately, the Ottomans, with assistance from the French, found alternative financial support and terminated the negotiations, stating that none of the artifacts would be sold or transferred to foreign hands.

Century-long struggle for cultural dominance

The Ottoman Empire’s cultural and historical wealth was a target for many foreign powers, especially during its final years. “This museum agreement of 1913 is the last major example of foreign powers’ desire to accumulate and own Greek and Roman cultural artifacts,” Arslan added.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, many European states sought to possess ancient artifacts, but it was Wiegand’s plan, amid the empire’s financial collapse, that nearly succeeded.

“Theodor Wiegand viewed this as an opportunity to enrich German museums with some of the world’s most significant artifacts. In 1914, he even remarked that the Ottoman government would be unable to pay its employees’ salaries due to an upcoming holiday, suggesting that the plan should be revisited,” Arslan said.

This case highlights the long-standing ambition of wealthy nations to exploit the Ottoman Empire’s vulnerabilities and secure valuable artifacts, many of which remain in global institutions to this day.

Although this plot by Wiegand failed, it serves as a stark reminder of the international appetite for Türkiye’s historical treasures. Had the agreement been signed, some of the most important artifacts from Istanbul Archaeological Museum would have ended up in Prussian hands, altering the course of cultural history.

The incident underscores Türkiye’s resilience in preserving its rich heritage, despite immense pressure from foreign powers.