From Ottoman-era respect to Israeli restrictions at Church of Holy Sepulchre

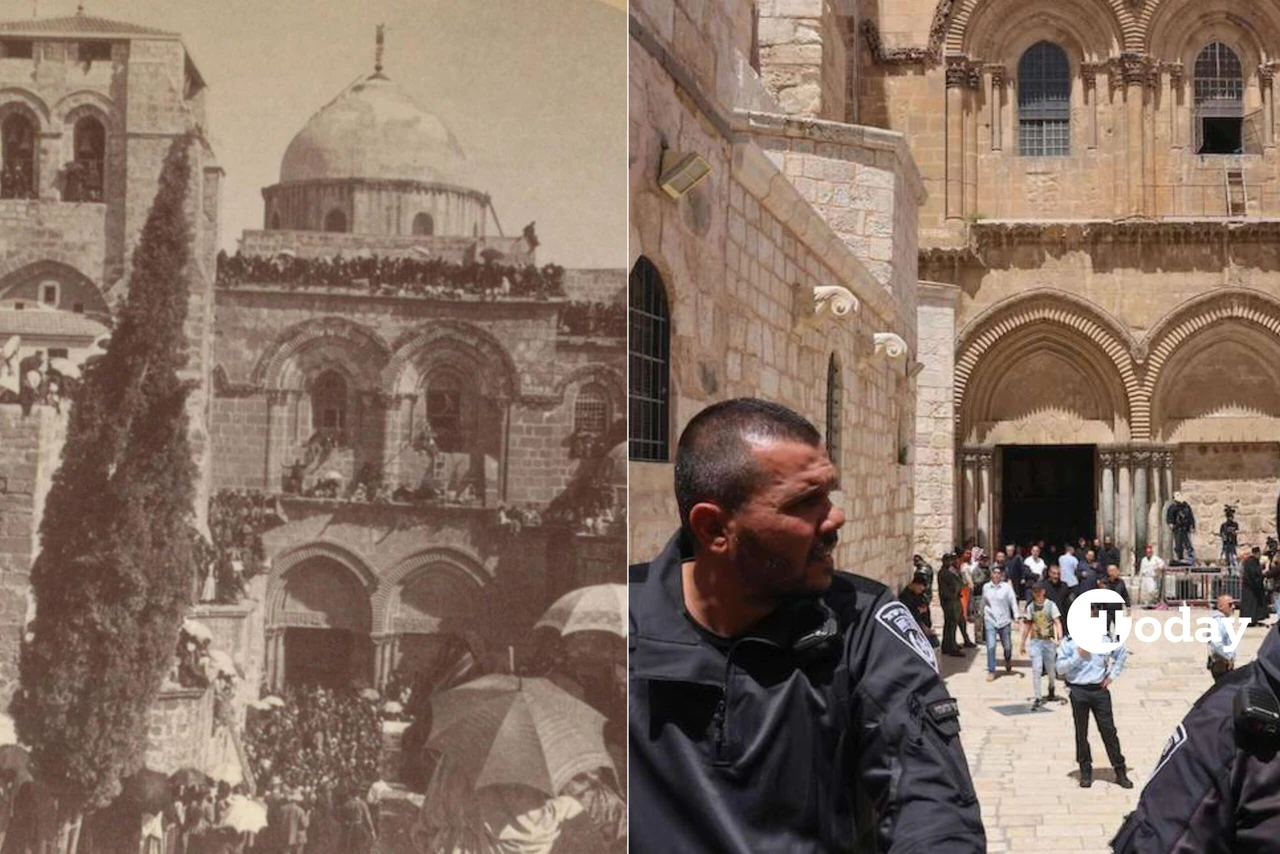

Left: Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem, 1899. Right: Israeli forces block Christian worshippers during Orthodox Easter, 2023. (Photo collage by Türkiye Today team)

Left: Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem, 1899. Right: Israeli forces block Christian worshippers during Orthodox Easter, 2023. (Photo collage by Türkiye Today team)

Jerusalem, the sacred city for three major faiths, has once again found itself at the intersection of faith, identity, and power. On April 20, 2025—Easter Sunday—tensions escalated in the church’s entrance as armed Israeli soldiers reportedly disrupted processions and pressured Palestinian Christians seeking to mark the resurrection of Prophet Jesus (peace upon him) at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Eyewitnesses and local Christian community leaders described an atmosphere of intimidation. Soldiers allegedly restricted access to churches, scrutinized pilgrims, and even forcibly blocked residents from entering their neighborhood chapels.

Many see this as part of a broader pattern of coercion targeting the dwindling Christian Palestinian community—a population that once thrived in the city.

A stark contrast: Easter in Ottoman Jerusalem

More than a century ago, under a very different regime, scenes from Easter Sunday told a different story. A 1916 article published in an American newspaper shows a Jerusalem where Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant processions were held openly and with reverence, under the auspices of the Ottoman Empire, then still at war in the Great War.

Archival photographs from that publication depict clergy and congregants walking through the streets, unbothered by military presence, despite the Empire’s own turbulent wartime conditions. The Ottoman authorities permitted and even facilitated religious expression in Jerusalem, not only for Muslims but also for Christians and Jews.

In 1904 alone, over 12,000 Christians—including European nobles, clergy, and diplomats—traveled to Jerusalem to celebrate Easter.

The Ottoman administration ensured safe passage and peaceful rituals, even when Easter coincided with Jewish Passover and the Muslim Nebi Musa festival. Far from clashing, the faithful coexisted under the empire’s careful oversight.

This peaceful coexistence, albeit under imperial rule, has become a reference point for those critiquing the current dynamics in modern-day Jerusalem.

A church shared, a faith fragmented

Today, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre remains divided among multiple Christian denominations—the Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Armenian, and Coptic churches—all of whom maintain fragile agreements over its use.

Beneath its chapels lies the site where St. Helena, mother of Constantine I, is said to have discovered the True Cross. Yet even this deeply symbolic history has not shielded it from modern political strife.

The current climate contrasts sharply with that pluralist Ottoman spirit. What was once a place of protected pilgrimage is now marked by checkpoints, restrictions, and confrontation.

From history’s lessons to today’s realities

As global attention turns to Jerusalem each Easter, questions arise: What does freedom of worship truly mean under occupation? Can historical models of coexistence offer pathways forward in today’s climate of division?

The Ottoman example suggests that religious freedom in Jerusalem is not a utopian ideal but a historical precedent. At a time when heavily armed forces silence worshipers at the gates of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, recalling that legacy is more than nostalgia—it’s a call to conscience.