Franco-Ottoman Marie Tepe: An American Civil War hero who fought for the Union

Born to a Turkish father and a French mother, Marie Brose Tepe Leonard, commonly known as “French Mary,” defied societal expectations by playing an active role in the American Civil War (1861-1865).

Though her Franco-Ottoman descent was rare in the 19th-century United States, she found her place in one of the most significant conflicts in American history, serving with distinction as a vivandiere for the Union Army.

Tepe’s story, offers a unique glimpse into the lives of women and ethnic minorities who contributed to the Union’s victory.

A rare Ottoman presence in the American Civil War

Born in Brest, France, on August 24, 1834, to a Turkish father and a French mother, Marie immigrated to the U.S. around the age of 15 following the death of her father. Ottoman immigrants were nearly unheard of in Civil War-era America, adding an extraordinary dimension to her presence on the battlefield.

In 1854, she married Philadelphia tailor Bernardo Tepe, and when the Civil War began, he enlisted in the 27th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Defying both gender roles and her husband’s wishes to stay home, Marie joined the regiment as a vivandiere, providing essential supplies and care for the troops.

Marie’s time with the 27th Pennsylvania was cut short by an unexpected incident. Sometime in late 1861, a group of intoxicated soldiers, including her own husband, raided her tent, stealing $1,600—a significant sum at the time. Though the men were punished, the betrayal left Marie so enraged that she refused to continue with the regiment. She also severed ties with her husband.

A fellow veteran noted, “She refused to have anything to do with her husband,” signaling the end of their partnership, both on and off the battlefield. Despite pleas from officers to stay, Marie left the 27th and forged a new path with another unit.

Franco-Ottoman’s new start with Collis’ Zouaves

In 1862, Marie joined the 114th Pennsylvania, also known as Collis’ Zouaves, where she fully embraced her role as a vivandiere.

Adopting a striking uniform inspired by those worn by French women in military camps, Marie wore a blue jacket, red-trimmed skirt, and red trousers—complete with a sailor’s hat.

Her Ottoman heritage and French-inspired uniform distinguished her visually and culturally from the rest of the regiment.

Zouave regiments, while not directly linked to the Ottoman military, drew inspiration from the early 19th-century uniforms of the reformed Ottoman Army.

The term “Zouave” originally referred to a group of Berber tribal troops in Ottoman service. By the 1830s, these soldiers came under French command, and their tactics and distinctive attire began to influence various military units, including the American militia.

Notably, even Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II established a Zouave unit in 1880, likely influenced by American Zouave regiments, as part of his royal guard. However, by that time, American forces had already ceased using Zouave-style uniforms. This connection to Ottoman military history added another layer to Marie’s experience, as she donned attire reminiscent of a tradition that had both shaped and transformed under the pressures of war.

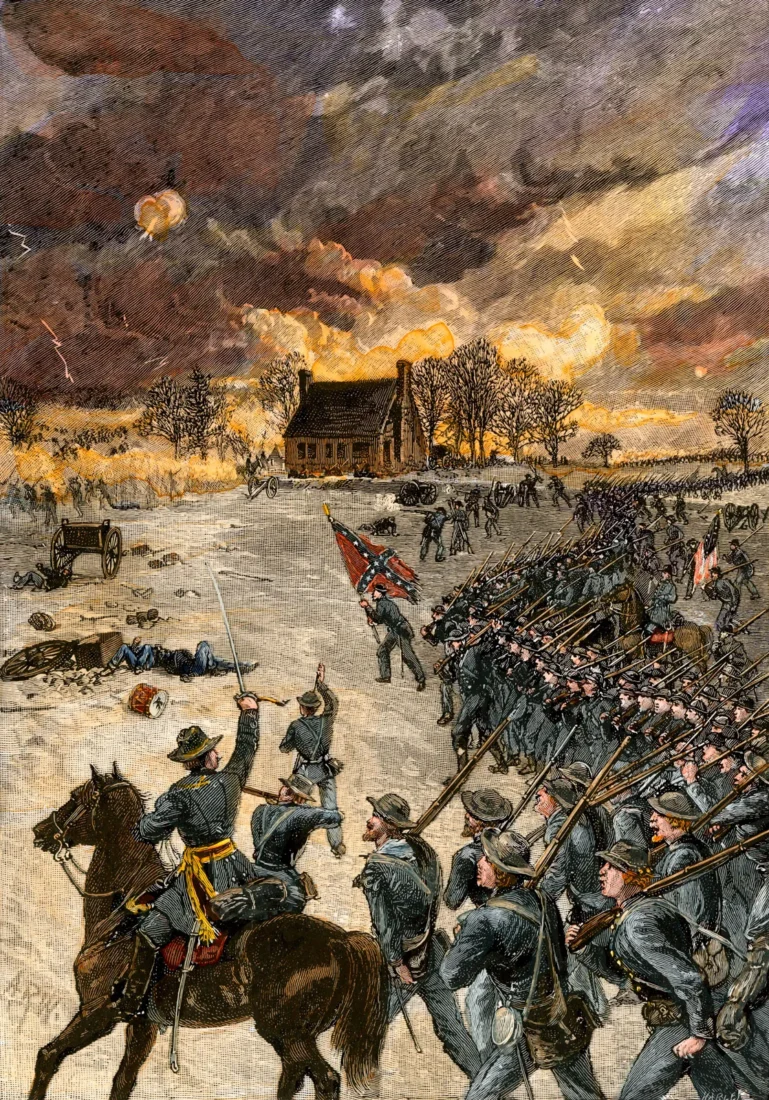

Tepe became a key figure within the 114th, serving in battles including Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. She was often seen carrying a keg of whiskey or water strapped to her shoulder, supplying soldiers with much-needed rations while they fought. When not in combat, she cooked, mended clothing, and tended to the wounded.

Tepe in the battle: Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville

Marie’s bravery during the Battle of Fredericksburg earned her wide admiration. On December 13, 1862, she was helping establish a field hospital when she was wounded by a bullet in her left ankle. Her courage did not go unnoticed. Shortly after, Lt. Col. Cavada presented her with a silver cup inscribed, “To Marie, for noble conduct on the field of battle.” Col. Charles Collis also wrote to commend her for her bravery.

At the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, Tepe’s actions again placed her in the spotlight. She worked tirelessly at a field hospital, bringing water to wounded soldiers while under fire. For her efforts, she was awarded the prestigious “Kearny Cross,” an honor given to only a few, including her fellow vivandière Annie Etheridge. However, Marie refused to wear the medal, telling her comrades that she did not seek recognition from General Birney, who had granted it. A witness recalled, “Her skirts were riddled by bullets during the battle of Chancellorsville.”

Tepe’s financial struggles were well-documented throughout the war. As a sutler, she often sold tobacco, cigars, and whiskey to soldiers, earning a soldier’s pay with an additional allowance for her work in the hospitals. Yet, even this enterprising spirit faced setbacks. At Brandy Station, Virginia, in the winter of 1864, Marie fell victim to the gambling craze that swept through army camps. After losing $50—a large sum at the time—she vowed never to gamble again.

Marie’s life after the Civil War

Following the war, Marie’s life took a difficult turn. After mustering out with the 114th Pennsylvania, she married Richard Leonard, a fellow Civil War veteran from Company K, 1st Maryland Cavalry. The couple settled near Pittsburgh, but their relationship was fraught with challenges. In 1897, Marie filed for divorce, citing “general abuse” as the cause of their separation.

Despite her war service and personal struggles, Tepe never received a military pension. An 1898 newspaper article reported her failed attempts to secure compensation for her contributions, leaving her in financial ruin. By the end of her life, she suffered from severe rheumatism and the lingering effects of the bullet lodged in her ankle.

Tragically, on May 24, 1901, after years of suffering and isolation, Marie took her own life by ingesting Paris Green, a toxic pesticide. Her few remaining possessions, valued at just $31.35, were left to her estranged husband in her will.

Marie’s unmarked grave and delayed recognition

Marie Tepe’s grave at St. Paul’s Cemetery in Carrick, Pennsylvania, remained unmarked for nearly a century.

It wasn’t until 1988 that a headstone was erected in her honor, following efforts by Civil War historians and reenactors to ensure her contributions were properly recognized.

At the dedication ceremony, attendees reflected on the significance of honoring a woman of Ottoman descent who had played a vital role in the Civil War.

Today, Marie Tepe’s legacy is a reminder of the diverse backgrounds of those who served the Union, and of the women who defied gender roles to make their mark on history. Her story—rooted in her Turkish and French heritage—adds a unique chapter to the annals of the Civil War.