Debunking claims about Gobeklitepe

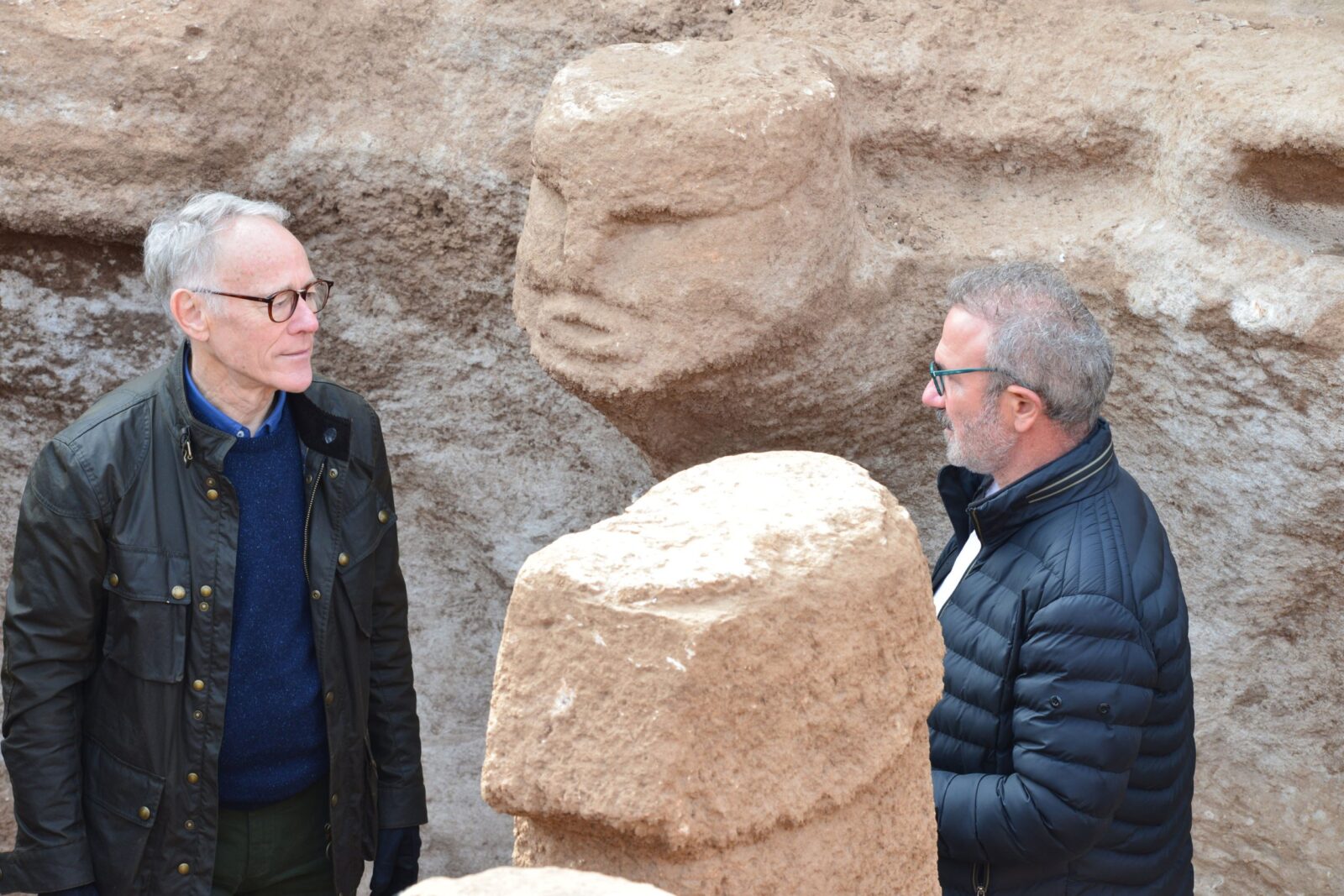

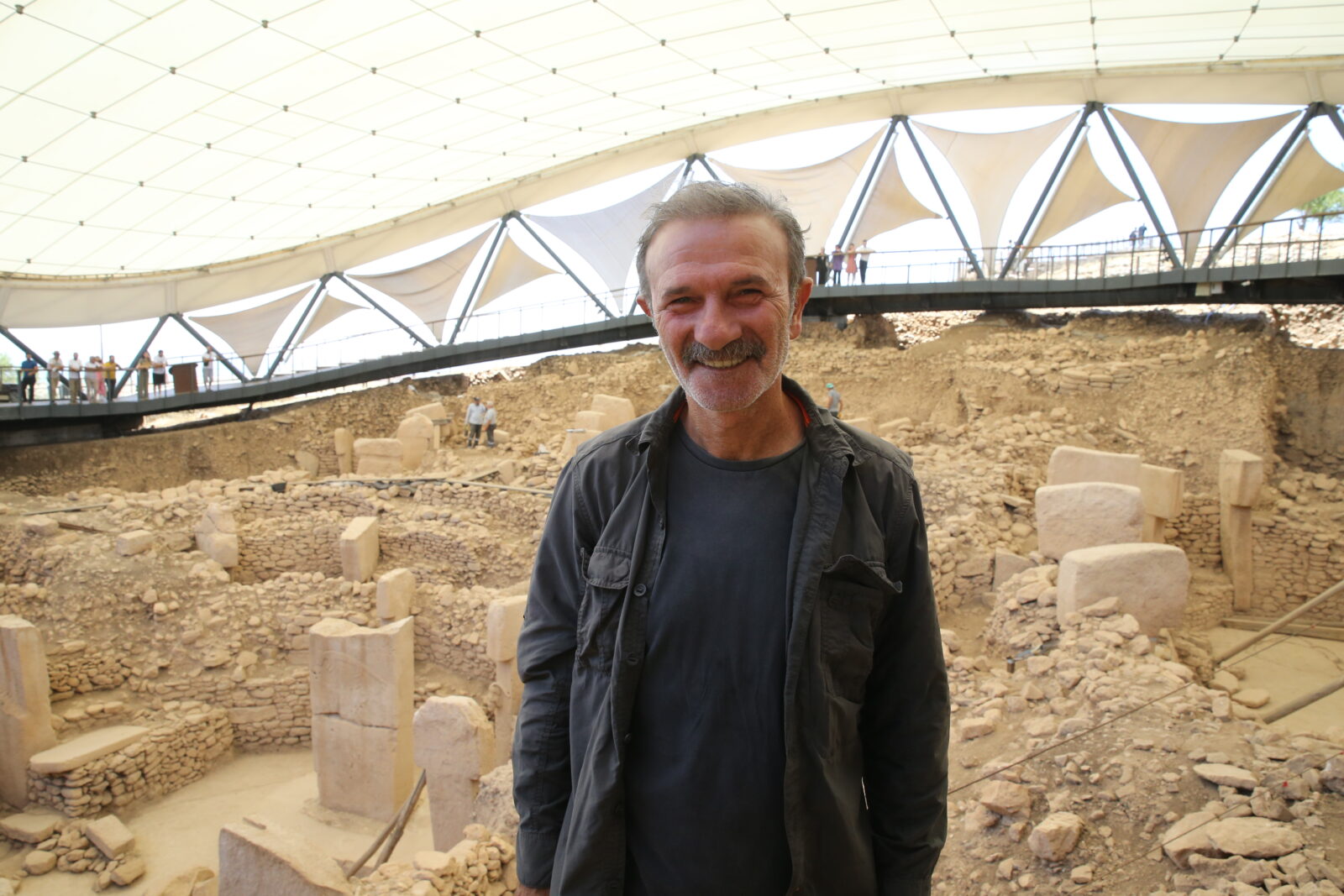

Inside the frame is "P43," with the protective roofing structure built in Gobeklitepe visible in the background, November 8, 2024. (Photo collage by Tugce Atmaca/Türkiye Today)

Inside the frame is "P43," with the protective roofing structure built in Gobeklitepe visible in the background, November 8, 2024. (Photo collage by Tugce Atmaca/Türkiye Today)

There have long been rumors and speculations surrounding the enigmatic, neolithic Gobeklitepe site, which is considered to be the world’s oldest communal complex.

Graham Hancock, a pseudo-archaeologist known for his controversial books and the “Ancient Apocalypse” Netflix series, has suggested connections between the site and early astronomical knowledge, as well as the ruins being a forerunner to an ancient apocalypse theory.

Contrary to this theory, Tas Tepeler (Stone Mounds) Project Coordinator Professor Necmi Karul, prefers to define depictions as “expressions of known stories from the past, which hold an important place in the construction of a new social order.”

Professor Necmi Karul prefers to define depictions as “expressions of known stories from the past, which hold an important place in the construction of a new social order.”

Türkiye Today set out to visit Gobeklitepe and explore it firsthand. With insights from local experts and reports from Türkiye Gazetesi newspaper and Arkeofili, along with information from the Gobeklitepe excavation team, we aim to separate fact from fiction and uncover the true significance of this remarkable archaeological treasure.

Astrological claims about Gobeklitepe’s role questioned

Controversy ensued with the publication of a study by two researchers from the University of Edinburgh, who suggested that Gobeklitepe’s structures served as an astronomical observatory.

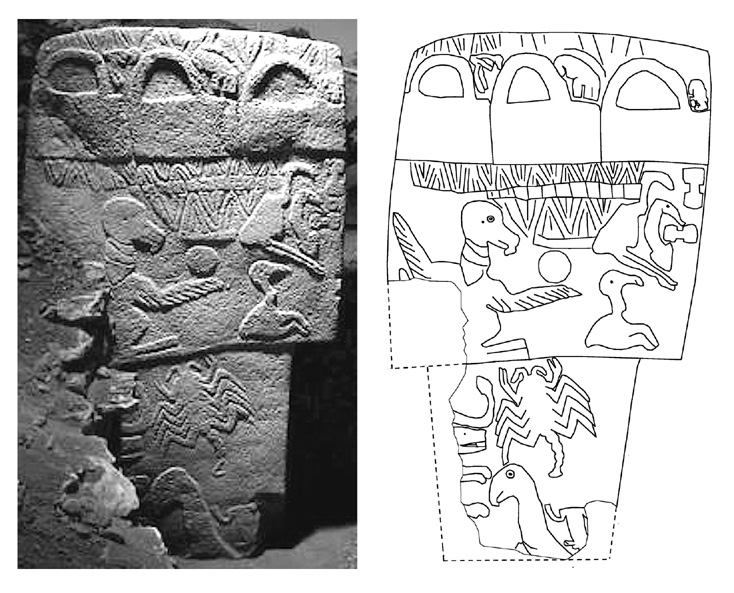

According to their study, the carvings on the T-shaped pillars, particularly those on Pillar 43, could represent a depiction of a catastrophic meteor strike that occurred some 12,000 years ago, an event linked to the “Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis.”

However, Jens Notroff and his colleagues argue that these claims oversimplify the findings. They point out that while Gobeklitepe has long been associated with astronomical studies, there is no concrete evidence linking its structures to celestial alignments or the observation of specific stars.

Notroff also criticized the lack of attention given to recent research that provides a more nuanced understanding of the site’s function.

Gobeklitepe’s purpose: Place of ritual, not observatory

Notroff elaborated on several issues with the study’s conclusions, particularly the idea that the round structures discovered in the third layer of Gobeklitepe may have been used as observatories.

“There’s a high probability that these structures were roofed and buried buildings, which makes it unlikely that they were used for stargazing,” he said.

He also questioned whether prehistoric humans defined constellations in the same way we do today, noting that much of our modern understanding of star groupings is based on ancient Egyptian, Babylonian and Greek astronomy.

Furthermore, Notroff pointed out that the study failed to consider many important details from the site’s iconography, such as the deliberate focus on specific animals in different contexts.

For example, he pointed out that the so-called “headless male figure” on Pillar 43 is interpreted by some as a symbol of death and mass extinction, but this interpretation overlooks other details, like the erect phallus, which complicates the narrative of simple death.

Hancock’s star map theory for Gobeklitepe, Karul debunks

The controversy over Gobeklitepe deepened when British author Graham Hancock, known for his Netflix documentary on ancient civilizations, suggested that the carvings on Pillar 43 could be star maps or diagrams of constellations.

However, professor Necmi Karul of Istanbul University’s Archeology Department, who leads the excavations at Gobeklitepe vehemently disagreed with this interpretation.

“He visited Karahantepe and created a documentary, using our findings to support his own theories. His interpretations of the carvings are not based on solid archaeological evidence,” he told Murat Oztekin from Türkiye Gazetesi.

Hancock is a controversial figure who proposes alternative theories about our past. Describing himself as a “free thinker,” Hancock accuses mainstream archaeologists of trying to cover up evidence of ancient super-advanced civilizations. His most well-known theory is about a lost civilization that vanished around 12,800 years ago during the Younger Dryas period.

Although Hancock visits various archaeological sites to support his theories, the scientific community rejects his views. Critics argue that his ideas are mostly speculative and lack credibility.

Karul concluded that while the site’s carvings are undoubtedly rich in meaning, their true purpose is likely rooted in mythology and collective memory rather than astronomical phenomena.

Gobeklitepe’s advanced architecture: Reflection of human ingenuity

Karul also addressed claims by engineer Martin Sweatman at the University of Edinburgh, who suggested that Gobeklitepe was an observatory. Karul countered that no concrete evidence supports this theory.

“The structures at Gobeklitepe are not observatories. We’ve found wooden traces that suggest the site’s structures were roofed, and no astronomical evidence has been found to support the observatory theory,” Karul explained.

He also emphasized that the site’s geometry should not be automatically linked to astronomy. “The people of that time were highly skilled in architecture and had a deep understanding of their environment,” he said.

Karul pointed out that the intricate carvings and the use of materials at Gobeklitepe show a sophisticated understanding of construction, but do not necessarily indicate astronomical purposes.

What do carvings on Gobeklitepe’s Pillar 43 really mean?

On Pillar 43, a vulture holding a skull is depicted, with a headless human body shown in the lower right corner. In Neolithic burial traditions, the dead were often fed to vultures, after which the skull was separated from the body. When only the skull remained, it was coated with materials like clay and plaster and painted.

The aim was to give the skull a realistic facial expression, and a shaman figure, wearing the vulture costume and holding the skull, likely performed this ritual.

The three symbols at the top could represent baskets used to carry the body. This skull cult suggests that Neolithic people believed the distinction between the dead and the living was not absolute. Many similar examples can be found in Anatolia. One of the best examples is the “Skull Structure” at Cayonu in Diyarbakir, where over 400 skulls were stored.

The vulture cult is still observed among various local communities. For instance, in Central Asia, people arrange corpses and bring them to certain spots in the mountains for vultures.

In Zoroastrian funeral rites, bodies were left on the roofs of buildings called “dakhmas,” where ravens and crows, also fed on human corpses, are found alongside vultures. These dakhmas were still in use in Iran until the 20th century.

Gobeklitepe continues to be a source of fascination and debate, with competing theories and speculations, often overshadowing the site’s true purpose.

The focus on animals, the vulture cult, and the evidence of Neolithic burial practices offer a clearer understanding of the site’s function as a space dedicated to death rituals, collective memory and mythology.