Challenges, regulations of migration to Ottoman Istanbul

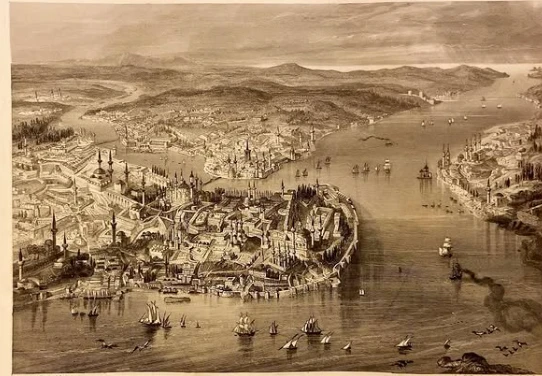

View of Ottoman Istanbul in late 1800s. Image published by Reinhold Publishing House in Berlin in 1890. (Austrian State Archive).

View of Ottoman Istanbul in late 1800s. Image published by Reinhold Publishing House in Berlin in 1890. (Austrian State Archive).

Undoubtedly, in pre-industrial societies, the vast majority of the population resided in rural areas. This was particularly true for major empires with traditional economies, such as the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman Empires. The contemporary Iranian-Persian Empire shared this system.

The economies of these empires relied on agriculture, mining to supply arms and expenditures, and nomads to meet the production needs of a significant portion of the population. The latter group not only provide essential goods like meat and milk but also crucial by-products of animal husbandry, such as leather and carpets. This production was vital not only for the market economy’s exchange conditions but also for the state’s diplomatic and, most importantly, military expenditures. In these empires, a monopoly was established over this production for military equipment.

This compulsory monopoly ensured the supply of weapons, military gear, and luxury goods for diplomatic gifts and exchanges. The Byzantine and Ottoman Empires exchanged valuable gifts with neighboring states or tribes, which could be considered a form of taxation or reciprocal gifting. Similarly, the population engaged in these sectors could not easily shift to other production areas or abandon their occupations. For instance, rice cultivation, essential for the Roman, Iranian, or Turkish empires, was primarily conducted in Upper Mesopotamia.

This product was also crucial and strategic for the army. The Ottoman Empire, for example, felt, a product of sheep husbandry, was necessary for the military classes, and its production was strictly controlled. Therefore, the rural population could not relocate freely. A declining population would undermine tax revenues and strategic product reserves. Moreover, urban craft production was also limited. Prices and raw material supplies were fixed. An excess urban population would lead to shortages or, as in the textile industry, the production of cheaper but lower-quality goods. Thus, early modern cities did not favor large populations.

Capitals lacked the capacity to support excessive residents

The capitals of the Roman Empires, Rome in Italy and Constantinople in Bithynia, had exceptional organizations to meet their needs. Egypt was a crucial grain source for Rome, along with North Africa, Pannonia, and Thrace via the Via Egnatia. For Constantinople, besides Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Balkans, and Crimea in the Black Sea region were important.

Beyond these, neither city had the capacity to support an excessive population, nor could the rural areas afford to lose both taxes and produce due to mass migration. In the Roman Empire, farmers were tied to the land, which was under the status of miri. The farmer’s right to the miri was limited to cultivation; the right of use was hereditary, but ownership belonged to the state. Farmers were bound to their land; if they left or fled, they would be captured and returned. Only after ten years in another location was it impossible and forbidden to bring them back.

During this period, the land would be given to another farmer for cultivation. Employment opportunities for migrants in cities were also very limited. The gedik system, guilds, or fraternities allowed only a limited number of apprentices and masters to work. In some cases, single men, especially from Eastern Anatolia, migrated to large cities for construction work, requiring a guarantor from their community.

Becoming a soldier in the provinces was a privilege. During the 16th and 17th centuries, some unemployed and vagrant youths joined the forces of rebellious governors. These individuals were called Levend, Sarıca, or Sekban. Alongside these Persian terms, the Ottoman administration used terms like düzmece (fake), saplama (intruder), and ecnebi (foreigner). These terms should be understood in the context of ancient empires rather than feudal European law.

Significance, control of food and water

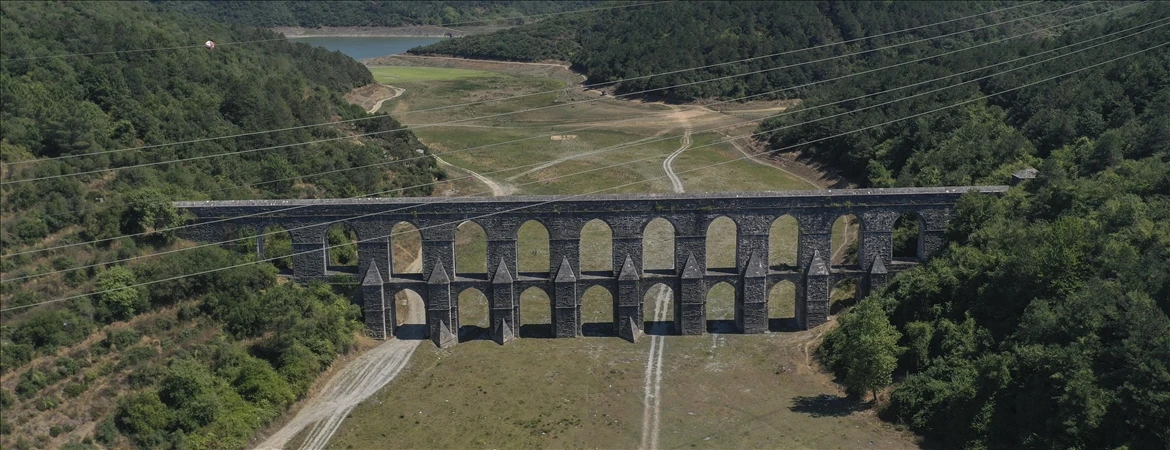

The problems caused by overpopulation in cities, particularly in the metropolis of Istanbul, were evident, and efforts were made to prevent them. In addition to controlling migration, water scarcity prevented everyone from building fountains or baths from existing water sources. Even for the construction of mosques and baths by the Grand Admiral Kilic Ali Pasha, imperial decrees were required.

When the chief imperial architect, Mimar Sinan, was building a fountain in front of his house, he was reported to have illegally tapped into the water supply. This matter was investigated by imperial decree. The use of city water for irrigating gardens and vineyards along the aqueducts was also prohibited. The greatest challenge in feeding the excess population was ensuring timely supply of meat and bread. Butchers who would bring sheep and livestock from Rumelia (Ottoman Balkans) were carefully selected, and they were often granted compulsory monopolies.

In the early 17th century, when some Armenian butchers in Istanbul’s Armenian quarter, tasked with bringing sheep from neighboring regions, attempted to avoid this duty, they were required to pay compensation, as stipulated in their contract. To prevent the sale of fruits and grains from the Istanbul region to foreigners, restrictions were imposed. Furthermore, a mechanism was established to prevent local butchers from selling animal hides abroad. The primary concern was always ensuring food and clothing for the surplus population. In a 16th-century incident, the warehouses of some butchers were raided, and 5,408 sheep and cattle hides intended for export to Venice were confiscated.

Istanbul’s historic migration troubles

In the case of Istanbul, migration was a major problem. For instance, there were two decrees from 1734 to apprehend and send back Albanians who had settled just outside the city walls to avoid security checks. The unwanted surplus population, especially if single, was seen as a potential danger in terms of hunger, banditry, and politics.

A decree from Ramadan 1734, following the Patrona Halil uprising, ordered the expulsion of all single Albanians. Raids were frequently conducted in inns and worker quarters, and those caught without permits were exiled from Istanbul. In a peculiar population policy measure, men who married prostitutes identified in the city were also ordered to be exiled, indicating a desire to prevent the settlement and growth of the problematic population.

Migration was not only a problem of peasants from Anatolia and the Balkans or crime-prone individuals entering the city. The population residing along the Bosphorus in Istanbul was also discouraged from settling and mingling within the city walls. However, during severe winters, residents of the Bosphorus were allowed to migrate to the inner city. This practice continued into the 18th century. Istanbul’s population was always subject to counts.

While the extent of our knowledge of Byzantine-era population counts is limited, Ottoman-era documents provide information about all the crafts in Istanbul. Besides these valuable sources for understanding the city’s economic potential and population, we have another important comparative resource: the kadı sicilleri (court records), which number in the thousands.

For 17th-century Istanbul, the most significant list of artisans is that of the famous traveler Evliya Celebi, which provides information on all crafts and guilds. Frequent analyses of population and building numbers necessitate revisions to our understanding of classical Istanbul histories. For example, the population and building counts conducted in Pera after the 1453 conquest, where Genoese, Venetians, and Greeks lived, are invaluable. The total number of these three groups did not exceed a few thousand. After the 15th century, Jews from Spain and Italy, Arabs from Andalusia, and Karaite Jews from Crimea were brought to Istanbul. This was a systematic population resettlement, as the Tophane and Tersane (arsenal and shipyard) were established nearby.

At this point, the question arises: How should the regulation of migration be addressed within the empire’s legal framework? Ottoman law was based on three sources: Sharia (Islamic law based on the Quran and Hadith), laws enacted by the ruler (provided they did not contradict Sharia), and customs and traditions (provided they did not contradict the first two). Laws and regulations governing migration and population policies were primarily based on the second source, i.e., imperial decrees and law codes.

Consequently, the restrictions, prohibitions, and regulations imposed by these laws became obsolete in the age of industrialization and impossible to enforce. Especially after the outbreak of World War I, the exemptions from military service and certain taxes for Istanbul residents were completely abolished.

Conversely, while elections for provincial and district administrative councils were held in all imperial provinces in the 19th century, they were not held in Istanbul until 1908. Over an extended period, migration policies towards Istanbul underwent significant changes from the modern era onwards.