Bloodiest uprising in Istanbul: Nika riot of the 6th century

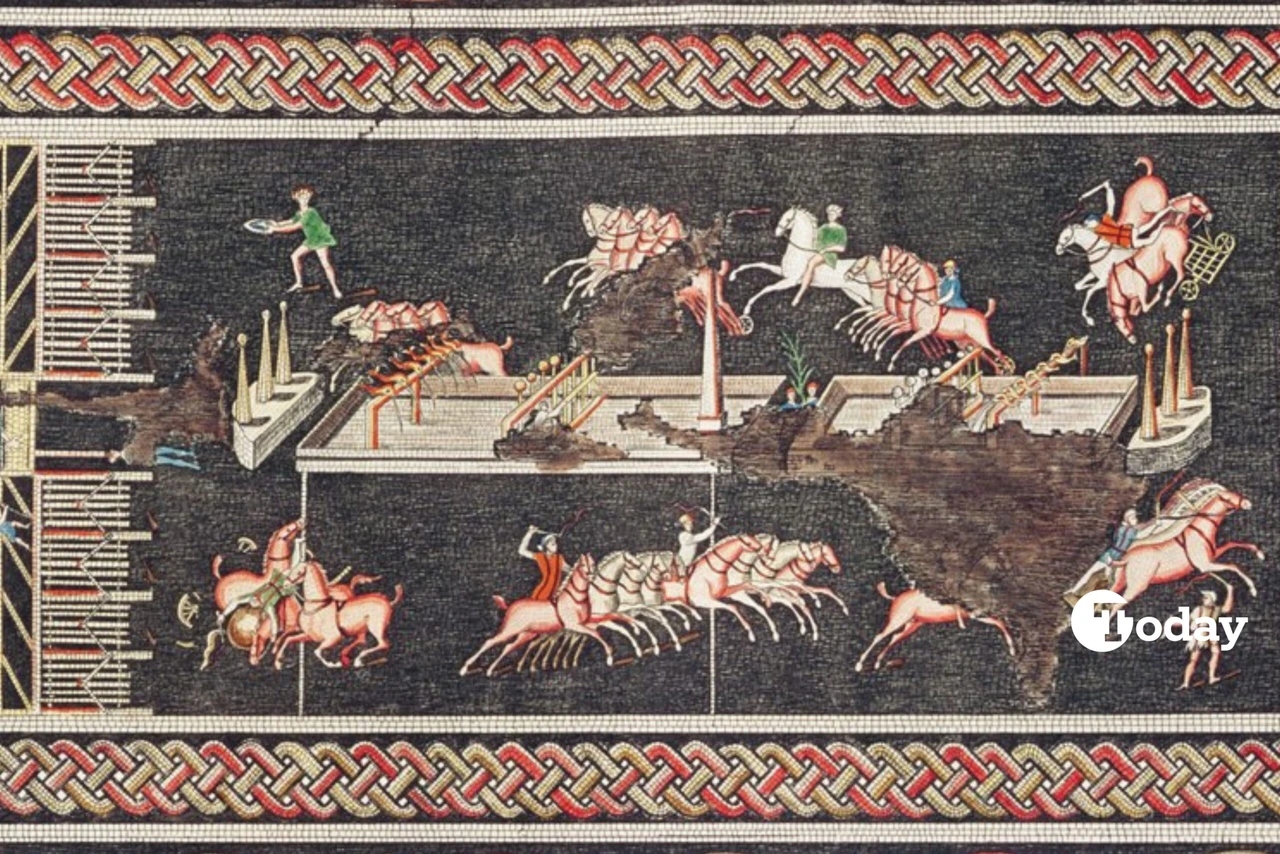

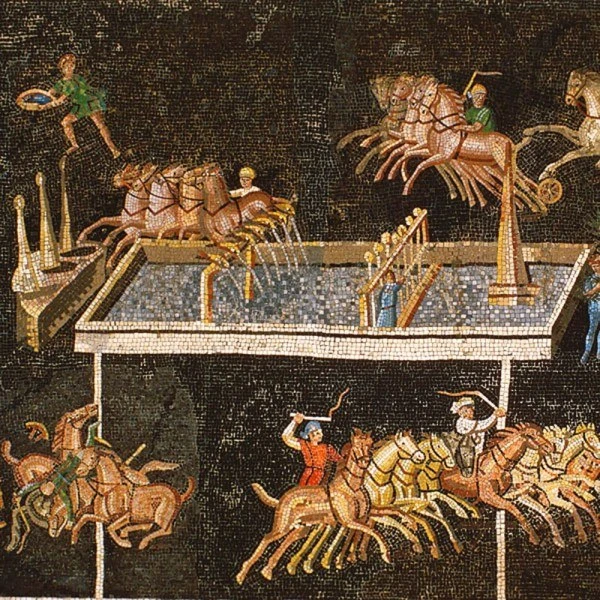

Representation of a mosaic discovered in Lyon depicting games; The colors of the Red, Blue, Green and White teams are clearly visible in the game. (Photo via 1st Art Gallery)

Representation of a mosaic discovered in Lyon depicting games; The colors of the Red, Blue, Green and White teams are clearly visible in the game. (Photo via 1st Art Gallery)

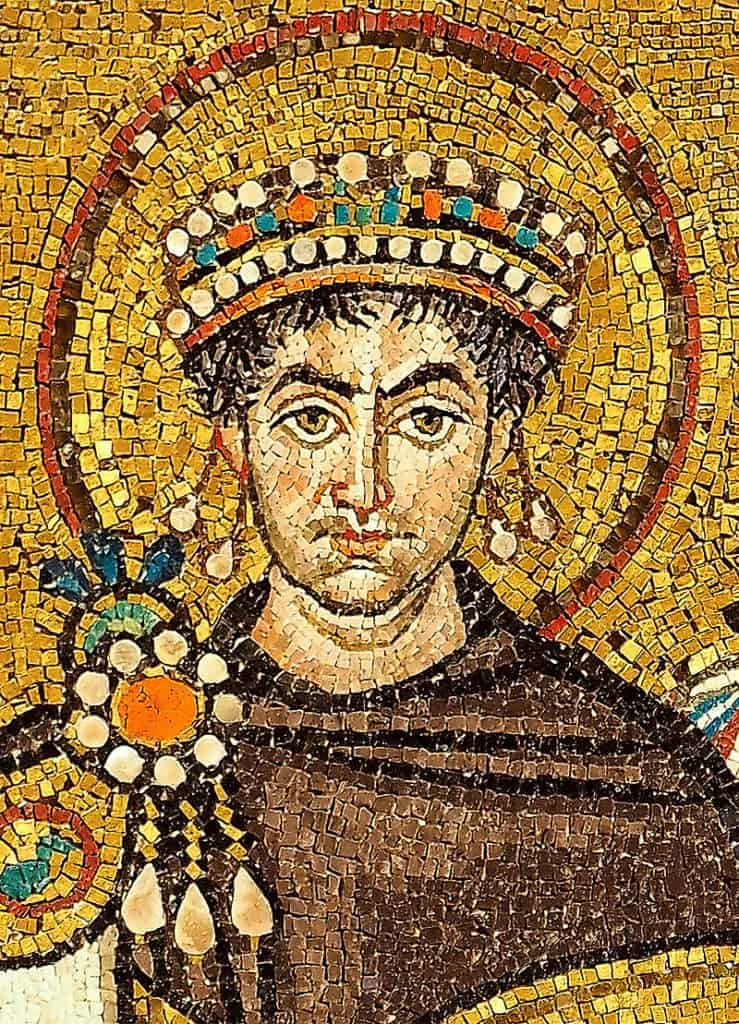

In January 532 A.D., the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) capital of Constantinople was shaken by one of the most violent uprisings in its history—the Nika riot. The turmoil nearly cost Emperor Iustinianus I (527-565) his throne. The rebellion took its name from the Greek word “Nika,” meaning “Victory,” which was the rallying cry of chariot-racing fans at the city’s Hippodrome.

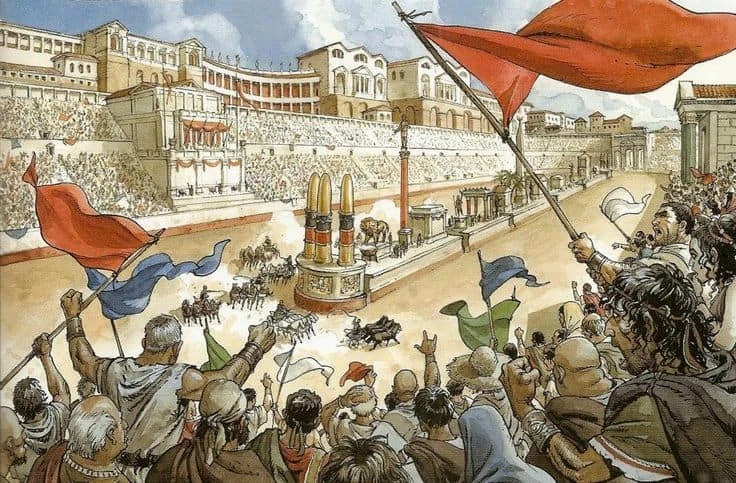

Chariot racing was more than just entertainment; it was a deeply ingrained social phenomenon. By the time of Iustinianus’ rule, gladiator fights and wild beast hunts had already been banned, leaving chariot races and theatrical performances as the main public spectacles. The Hippodrome could hold nearly 100,000 spectators, and its races were dominated by four factions—Blues, Greens, Reds, and Whites—named after their colors. The Blues and Greens were the most influential, often clashing violently, not only with each other but also with city guards. These factions were not just sports clubs; they wielded political and financial power, sometimes even influencing imperial policies.

The emperor and factions: A dangerous alliance

Byzantine emperors frequently aligned themselves with these factions. For example, Emperor Theodosius II (408-450) supported the Greens, while both Iustin I (518-527) and his successor, Iustinianus I (Iustinian), were allied with the Blues. This favoritism helped rulers secure public support but also led to violent rivalries. During the reign of Emperor Anastasius I (491-518), his backing of the Reds angered both the Blues and the Greens, triggering further unrest.

The Hippodrome was more than a sports venue; it was a political stage where citizens could voice grievances directly to the emperor. Crowds often used synchronized chants to demand dismissals of unpopular officials or complain about high food prices. Past emperors, including Anastasius I, had mastered the art of public appeasement, sometimes making symbolic gestures to calm the masses.

The spark that ignited the Nika riot

By the early sixth century, the fanaticism of the chariot factions had escalated to dangerous levels. Iustinian’s open support for the Blues shielded them from legal consequences, but his rigid policies alienated even his former allies. Tensions erupted into open rebellion on Jan. 10, 532, when the city’s governor, Eudemonos, ordered the execution of seven faction members accused of murder in the district of Sykai (modern-day Galata). Two of the condemned men—one from the Blues and one from the Greens—miraculously survived their hanging when the ropes snapped. They were rescued and hidden in a nearby monastery, which was soon surrounded by imperial troops.

On Jan. 13, spectators in the Hippodrome demanded clemency for the fugitives. When Iustinian ignored them, the factions united under the defiant chant of “Nika!”—and the riot began. The rebels stormed government buildings, torched the governor’s headquarters, and forced the emperor into hiding within his palace. Desperate to defuse the crisis, Iustinian extended the chariot races into the following day, but the violence only escalated, with mobs setting fire to vast sections of the city.

Political conspiracies and rise of rival emperor

The rebels, emboldened by the emperor’s hesitancy, pushed further. They demanded the dismissal of key officials, including Governor Eudemonos, the commander of the imperial guards, and the emperor’s chief legal advisor, Tribonianus. Sensing an opportunity, members of the aristocracy who opposed Iustinian supported the uprising from behind the scenes. When Iustinian dismissed the unpopular officials, the crowds remained unsatisfied. The situation worsened when the rioters declared Hypatius, a nephew of former Emperor Anastasius I, as their new ruler.

Fearing for his life, Iustinian considered fleeing the city. However, his influential wife, Empress Theodora, intervened, famously declaring that she would rather die an empress than live in exile. Her resolve convinced the emperor to take decisive action.

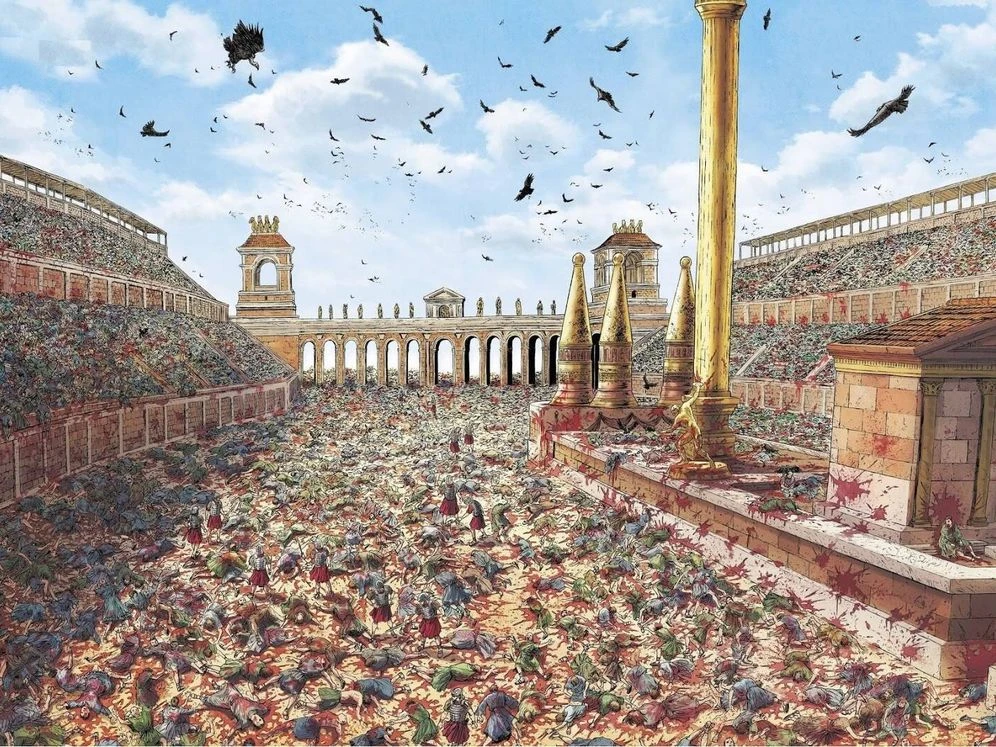

The massacre that ended the Nika riot

On Jan. 18, Iustinian deployed his most trusted generals, Belisarius and Mundus, along with their elite troops. The soldiers sealed off the Hippodrome, where thousands of rioters had gathered. In a brutal crackdown, imperial forces massacred over 30,000 rebels. Hypatius was captured and executed, and order was finally restored.

In the aftermath, Iustinian launched an ambitious reconstruction effort, including the rebuilding of the city’s most important religious structure, the Hagia Sophia. The rebellion had nearly ended his reign, but his swift retaliation solidified his power for decades to come.

Origins of political factions and support: Blues and Greens in ancient Rome

In the early second century, the Roman poet and writer Juvenal famously lamented that Romans had forsaken their political freedoms in exchange for “bread and circuses” (panem et circenses). In his satirical works, Juvenal highlighted the Roman practice of distracting and placating the masses with free bread and entertainment, such as chariot races, instead of addressing real issues.

The phrase “bread and circuses” became a symbol of political manipulation, where emperors provided the public with diversions to prevent uprisings and secure their power.

Rise of chariot races: A form of Roman entertainment

From the early days of the Roman Empire, emperors used the Hippodrome as a tool to maintain public favor. Initially featuring gladiatorial combat, these spectacles gradually shifted toward chariot races, particularly after the rise of Christianity, which led to the banning of gladiatorial games.

Under Emperor Augustus, such events were held 77 days a year, costing the state heavily. However, by the early second century, during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the number of spectacle days had more than doubled to 135. The games continued to thrive until the Latin conquest of Constantinople in the 13th century.

The chariot races at the Hippodrome were organized by four teams, identified by their colors: Red, Blue, Green, and White. Over time, each of these teams gained its own fanbase, with supporters wearing cloaks in team colors and waving flags.

By the fourth century, the teams had become more politically significant, and only the Blue and Green factions remained. The crowds who supported these teams didn’t just cheer for their favorite competitors; they also used the races to voice political opinions, sometimes protesting issues like taxes, military service, or unpopular policies.

Political divisions: Blues as conservatives and Greens as rebels

The political rivalry between the Blues and the Greens was not just about sport but reflected deeper socio-political divides within Roman society. The Blues, representing the elite and conservative factions, were aligned with the Diophysite Orthodox belief, which had been established as the state religion following the decisions made at the Council of Chalcedon (modern-day Kadikoy, Istanbul) in 451.

The Greens, on the other hand, were more radical, supporting the Monophysite Orthodox doctrine, which contradicted the official religious stance. They were largely supported by the poorer, lower-class citizens, often from the Eastern regions of the empire. In this sense, the Blues and Greens can be seen as the first political parties, symbolizing the class struggles of the time.

Emperors and their factional loyalties

Interestingly, emperors often took sides in this political rivalry, reflecting their own personal and political beliefs. For instance, Emperor Iustinian, a devout supporter of the Diophysite faith, supported the Blues. Conversely, his wife, Empress Theodora, who had come from a poor background and was sympathetic to the Monophysite cause, supported the Greens. This division allowed the emperor and empress to maintain influence over both factions, ensuring that they remained in tune with the various political and social currents of their time.

The fierce competition between the Blues and Greens eventually erupted into violent conflict during the Nika riots in 532 A.D., which saw the factions turn against the emperor. The riots marked a crucial moment in the relationship between the imperial court and the public, highlighting the volatile intersection of sport, politics, and power in the Roman Empire.