‘Suitcases brimming with hope, fear, resilience’: Syrians return home after Assad’s fall

Syrian refugees return home following 61-year Baath regime collapse, from Kilis border crossing, in Kilis, Türkiye, Dec. 21, 2024. (Photo edited by Türkiye Today staff)

Syrian refugees return home following 61-year Baath regime collapse, from Kilis border crossing, in Kilis, Türkiye, Dec. 21, 2024. (Photo edited by Türkiye Today staff)

“Home.”

“They say home is where the heart is. What if you have your heart in two places? Can we own two (homes) in this world?” asked 15-year-old Ehtisham*, who was born and raised in Türkiye’s Kayseri but had always imagined Syria’s Damascus—the place his parents have always spoken of with quiet reverence—as his abode. Ehtisham completed his elementary schooling before joining a football academy in Türkiye, but now it’s time—time to return home.

Ehtisham, who aspires to become a prolific footballer like famed young Turkish football star Arda Guler, is one of the 3.2 million Syrian refugees Türkiye hosts, being one of the largest refugee host countries worldwide. Following the former Syrian regime leader Bashar al-Assad’s fall in Damascus on Dec. 8, the collapse of the 61-year Baath regime was celebrated with immense joy in Türkiye’s Istanbul. Jubilation, fear of the unknown, and hope permeated through the nooks and crannies of Fatih streets, among many other districts of the metropolis. “What’s next?” was the looming question on many minds.

‘I belong somewhere’

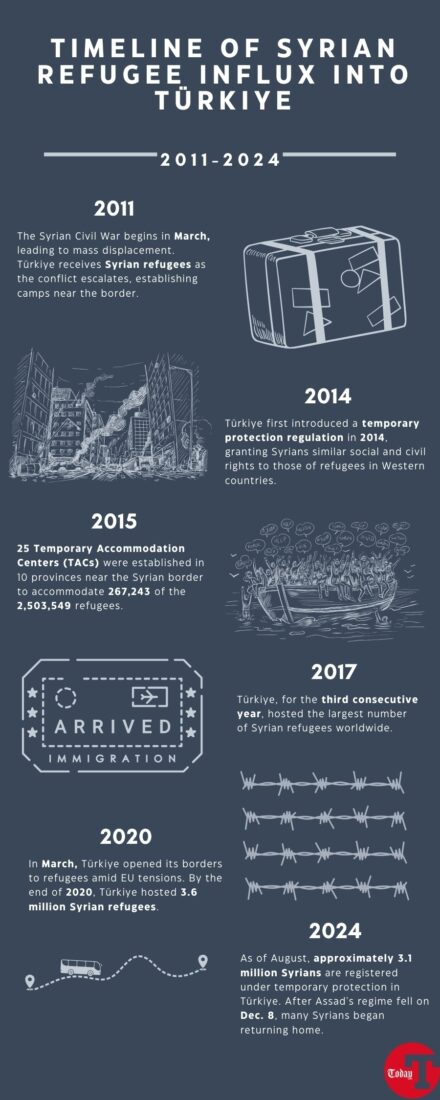

The significant influx of Syrian refugees into Türkiye occurred between 2012 and 2015, as millions fled the Syrian Civil War, escaping intensified conflict, economic woes, persecution, and human rights violations. However, with the dramatic fall of Assad’s dictatorship, many Syrian refugees are now seeking to return home—a longing they have passed on to the next generation.

“There were a million reasons for which we (had) left Syria, and all those million reasons are now gone,” said Yousef Saleh, a Syrian sociologist and social activist based in Istanbul. Saleh escaped the tyranny of the Assad regime, arriving in Türkiye from Aleppo in 2013 at the age of 22. Now, as a father of two, he envisions a future for his family in Syria.

“I am extremely happy. This is the first time in my life that I belong somewhere. This feeling of belonging is amazing,” Saleh shared, reflecting on the post-Assad era.

When asked about preparations for his voluntary return to Syria, including legal documentation, Saleh explained that the Turkish government has launched a portal to facilitate safe returns. “However, some Syrian refugees are reluctant to apply, as doing so means relinquishing their temporary protection ID and leaving Türkiye permanently. Nobody is forcing anyone right now, but uncertainty still looms large. We don’t know what will happen next. Some think it might be safer to wait and gauge the situation,” he noted.

Saleh added that the decision could become easier if Türkiye or other countries allowed temporary visits, which are currently unavailable. “People want to be sure before wrapping up their lives again and making such a drastic decision. This hesitation likely stems from the torment they’ve endured, compounded by years of displacement and fear,” he said with a sigh.

En route to Syria

Returnees are permitted to cross into Syria through designated border gates in Türkiye after completing the required documentation, with women and children prioritized throughout the process. As of December 2024, Ankara has opened several crossings to facilitate the safe and voluntary return of Syrian refugees to their homeland.

These crossings include the Cilvegozu Border Crossing near Antakya, which connects to the Bab al-Hawa gate in Syria, where hundreds of refugees have gathered in anticipation of returning. The Oncupinar Border Crossing near Kilis, connected to the Bab al-Salameh gate in Syria, has also seen significant numbers of refugees crossing. Additionally, the Yayladagi Border Gate in Hatay province is now open to support the safe return of Syrian migrants.

These measures are part of Türkiye’s broader efforts to manage refugee returns in line with recent political changes in Syria, with safeguards in place to ensure the safety and well-being of returnees. “I’m excited to return, but I don’t know what to expect. I feel more apprehensive than hopeful about what lies ahead,” Ehtisham shared, reflecting on his decision to leave the only home he has known.

Saleh, on the other hand, is eager to return to his city, though he acknowledged his family’s concerns about job opportunities and the standard of living in Syria. “Syrian refugees leaving Türkiye and returning home should be aware that life in Syria won’t be the same as it was in Türkiye,” Saleh emphasized.

According to United Nations projections, approximately 90% of Syria’s population remains below the poverty line. “Despite these challenges, I want to return home. Türkiye always reminds me that I am a Syrian,” Saleh said, pointing to the cultural divide, rising anti-Syrian sentiments in some areas, and the mounting economic crisis.

While reflecting on his years in Türkiye, Saleh fondly recalled his Turkish landlord, whom he affectionately calls “baba” (father in Turkish), praising his unwavering support over the years. “Acceptance is a process; it’s not about being a good or bad person. It’s about awareness,” Saleh observed, highlighting both the hardships and the acts of kindness that have shaped his journey in Türkiye.

Who are we?

With so much ambiguity surrounding the transition of Syrian refugees from Türkiye to Syria, another pressing issue often goes unnoticed. According to a 2021 UNICEF report, there were approximately 1.7 million Syrian refugee children in Türkiye. Given the current circumstances, a significant portion of the Syrian refugee population in Türkiye is likely under 18.

“The majority of Syrian refugees in Türkiye are teenagers or people in their early twenties. Having been born in Türkiye, attended Turkish schools, and formed deep connections with Turkish friends, many of these young Syrians don’t even speak Arabic. This transition will undoubtedly be pivotal and challenging for them,” Saleh noted. He explained that, despite his efforts to speak Arabic with his 9-year-old son at home, his son primarily uses Turkish as he attends a Turkish public school.

“I might not even continue my education when I go back to Syria because I don’t know Arabic,” admitted 12-year-old Noor, who never stepped outside Istanbul.

Experts warn that cultural differences, language barriers and contrasting social norms could trigger an identity crisis among young Syrians returning to Syria after being raised in Türkiye. Having grown up in a different cultural environment, many may struggle to adapt to Syria’s post-conflict realities and to build a sense of belonging to both countries. The dominance of Turkish in their upbringing and their limited fluency in Arabic may hinder their access to education, employment, and social integration.

“We might be perceived as ‘outsiders’ in Syria despite our roots and heritage, while in Türkiye we face discrimination as refugees. So, I ask myself sometimes: Who are we?” questioned Ehtisham, expressing concerns that dual exclusion could amplify feelings of alienation.

Despite these challenges, Saleh remains optimistic about the future. When asked about his outlook on life in Syria, he chuckled lightly. “Well, that’s a question you should ask me when I’m in Syria. To be honest, the future doesn’t worry me much—it’s something we’ll build together,” he said, exuding hope for better days ahead.

*Names have been changed to maintain anonymity.