Pakistan at crossroads: What lies ahead amid protests led by Imran Khan’s supporters?

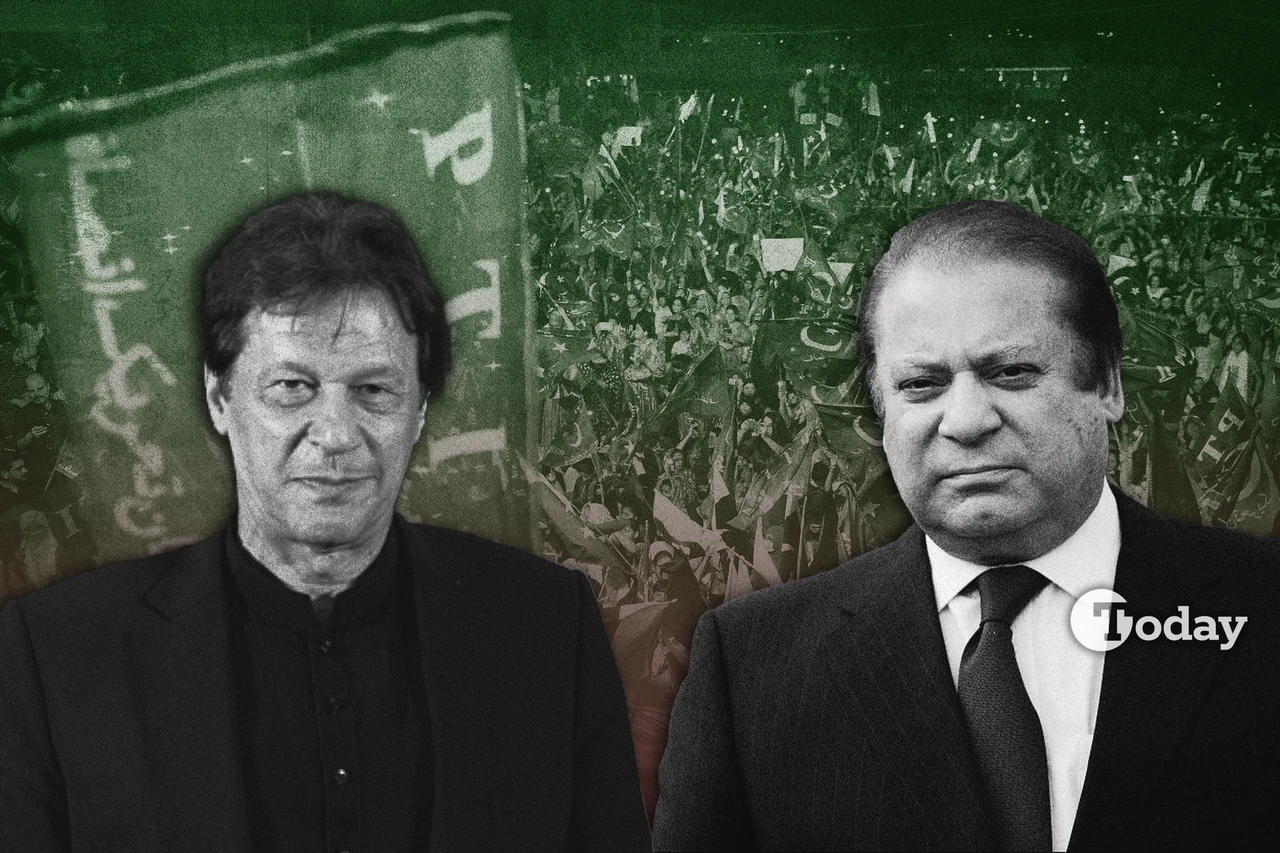

Imran Khan, 72, former Prime Minister of Pakistan (left), alongside Nawaz Sharif, three-time former PM (right) (Collage prepared by Türkiye Today team)

Imran Khan, 72, former Prime Minister of Pakistan (left), alongside Nawaz Sharif, three-time former PM (right) (Collage prepared by Türkiye Today team)

The ongoing political crisis in Pakistan, marked by widespread protests from Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) supporters demanding the release of former Prime Minister Imran Khan, is shaking the capital and the country.

With Islamabad under strict lockdown, mobile data services suspended, and over 4,000 arrests reported, tensions continue to escalate in a country already known for its volatile political landscape.

Officials from Khan’s party, PTI, claim that over 70,000 people are on their way to the capital. On Tuesday, the convoy is expected to reach Islamabad, where Khan is imprisoned. In the capital, areas housing government buildings have been blocked off with shipping containers. BBC correspondents report that the city is now being referred to as “container-abad”.

History repeating itself

Khan, who has been imprisoned for over a year and faces more than 150 criminal cases, remains a polarizing yet popular figure in Pakistani politics. Despite heavy security measures, his supporters have taken to the streets to call for his release and the current government’s resignation. Videos circulating on social media showcase PTI rallies characterized by fervent chants, dancing and defiance, even as authorities block roads and detain protesters.

The suspension of internet and mobile services during such protests has become a recurring theme in Pakistan. While the government defends these actions as necessary for “public safety,” critics view them as undemocratic measures aimed at stifling dissent. This trend has persisted across successive governments, and while regrettable, this has long been a tradition.

During the PTI government’s tenure, mobile and internet services were suspended on April 15, 2021, during a march called by Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan. Such actions are frequent but have never successfully ended protests. They temporarily control the situation, but people’s sentiments remain.

Echoes of Dhaka

The recent political unrest in Bangladesh, which led to the ousting of Sheikh Hasina, serves as a stark reminder of how mass protests and blockades near a nation’s capital can destabilize a government.

In Pakistan, a similar fear grips the ruling administration. According to Professor Samina Yasmeen from the University of Western Australia, the government’s anxiety stems from the unpredictable nature of large-scale demonstrations converging near key government buildings.

“The fear is essentially what happened even previously last year: once you have a whole lot of protesters coming inside very close to the seat of government, you never know what’s going to happen, and so that’s a security issue,” she explained.

The potential for protestors to occupy spaces near Parliament raises the specter of a weakened government image and intensifies concerns over political stability. This fear is compounded by the high number of arrests, which, as Yasmeen notes, “has the capacity to destabilize Pakistan further,” signaling both immediate security challenges and broader implications for national unity.

Why now?

The government of Pakistan claims that PTI has protested on every occasion when a significant international figure or event took place in the country, such as during the recent visit of the Belarusian president. The fact that the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit occurred without PTI’s protests in Islamabad is being touted as a success for the government.

Adaptive hegemony of military

In some countries, like Pakistan or Thailand, the military often positions itself as the ultimate guarantor of national unity or ideology, intervening whenever it perceives a threat to its interests or stability.

In Thailand, the military has staged numerous coups, most recently in 2014, alternating its support between royalist factions, pro-democracy movements and populist groups based on the prevailing political climate. Similarly, this dynamic has been evident in Pakistan’s current situation, where shifting alliances have allowed the military to adapt to changing political landscapes while maintaining its influence.

Historically, the military has played a decisive role in shaping the nation’s politics, often backing certain political parties or leaders to maintain its dominance. Imran Khan’s rise to power in 2018 was widely seen as such, facilitated by the military, just as his ouster and the current PML-N-led government are attributed to similar interference.

The military’s involvement in politics has undermined democratic norms and resulted in a culture of political instability. In the current crisis, allegations of manipulation—such as suspending the result management system during elections or misusing forms to alter results—highlight how the establishment continues to exert control over Pakistan’s electoral and governance processes as well.

While Türkiye once experienced a similar military dominance in politics, it has since curtailed the army’s influence, transitioning toward a civilian-led political framework. Since the failed coup attempt in 2016, the likelihood of such a threat has diminished. Consequently, periods of political instability can, at times, present opportunities for strategic realignments or reforms.

Scenarios for resolution: Can Türkiye play a role?

The path to resolving the crisis remains unclear. Negotiations between the government and PTI appear unlikely in the current climate of distrust and suppression. However, international mediation could offer a way forward. Türkiye, with its historical ties to Pakistan and a reputation for effective diplomacy, could emerge as a potential mediator. Ankara’s ability to address between warring parties, as demonstrated in its role in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, positions it as a credible actor in creating dialogue channels.

Speaking to Türkiye Today, Dr. Osama Shafiq from Bury College, U.K., remarked, “Internationally, there have been instances where foreign powers have supported political figures in Pakistan at critical moments, and at times, Pakistan’s government has declined such help. For example, Saudi Arabia facilitated Nawaz Sharif’s departure to Jeddah in 2000, and the U.S. played a role in Benazir Bhutto’s exile and return. Similarly, if Imran Khan wishes to leave the country now, the government might allow it, but it would require guarantees from a major country, and Türkiye could potentially play a role in this.”.

Mutual disengagement

Throughout the crackdown on Imran Khan and the PTI, including Khan’s imprisonment since August 2023, international actors have largely refrained from direct involvement, framing the situation as an internal matter for Pakistan.

The United States, for instance, has remained distant, citing limited interest in renewing a broader security or economic partnership and continuing to view Pakistan primarily through a counterterrorism lens. On the other hand, China, a key player in the region, has taken a similarly non-interventionist stance. With the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) being a flagship project under its Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing has prioritized maintaining its economic collaboration with the current government over engaging in Pakistan’s internal politics.

This mutual disengagement from internal conflicts and rivalries by both global powers creates an environment of external detachment. However, the democratic shortcomings on both sides—Pakistan’s internal challenges and the strategic pragmatism of its international partners—further complicate an already turbulent situation.

Not yet finished

The country’s political future remains uncertain as the nation faces ongoing protests, widespread arrests, and an uneasy relationship between its political camps. As Pakistan undergoes a period of political transition, it shows that the international arena is also witnessing a time of new process. In this context, global actors have largely opted for non-intervention, reflecting a broader recalibration of priorities and a focus on strategic interests over involvement in Pakistan’s internal challenges.

Domestically, the situation highlights longstanding issues with democratic norms and governance, including the military’s continued influence. While examples from regional neighbors show that reducing military dominance in politics is possible, Pakistan’s path forward will likely depend on its ability to address systemic challenges and rebuild the dialogue among political stakeholders again.