Leonardo da Vinci’s little-known proposal to Ottoman Sultan Bayezid

Sultan Bayezid II rejected Leonardo da Vinci’s visionary bridge design for the Golden Horn. (Created with Canva)

Sultan Bayezid II rejected Leonardo da Vinci’s visionary bridge design for the Golden Horn. (Created with Canva)

In 1502, during the height of the Renaissance, one of history’s greatest minds, Leonardo da Vinci, made a bold proposition to Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II, the ruler of the grand empire.

At the time, Sultan Bayezid sought innovative solutions for a significant infrastructure project – a bridge spanning the Golden Horn, a natural estuary in the Bosphorus that separated the historic city of Istanbul from the district of Galata.

The construction of such a bridge was both a practical necessity and a symbol of the sultan’s ambition to cement the Ottoman Empire’s status as a cultural and technological powerhouse.

Leonardo da Vinci, already renowned for his masterpieces like the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, was also a prolific inventor and engineer. He responded to sultan’s call with a proposal that was as visionary as it was ambitious: a bridge design that would be the longest of its kind in the world.

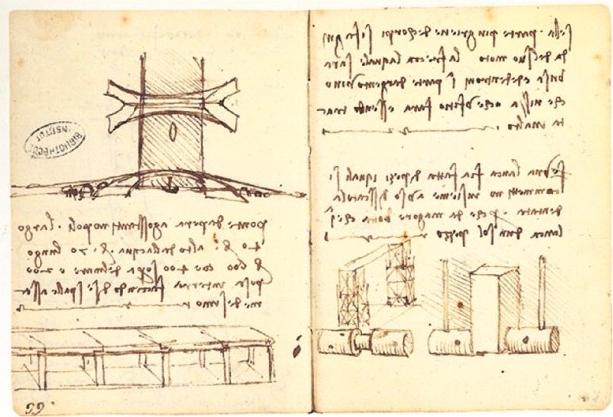

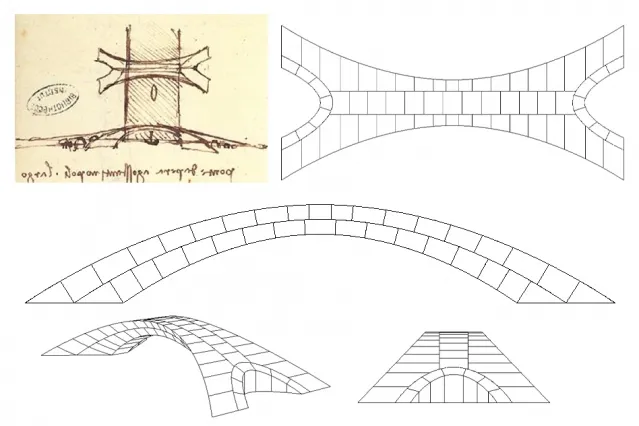

Da Vinci’s design featured a single flattened arch stretching 1,201 feet (366 meters) across the Golden Horn. This arch was designed to be tall enough to allow the passage of the tallest sailboats of the time, a critical feature given the Golden Horn’s role as a busy maritime route.

On the other hand, Istanbul sat on the North Anatolian Fault line, a region prone to frequent and sometimes devastating earthquakes. Understanding this, da Vinci’s bridge incorporated splayed abutments – wider supports at the ends of the bridge – to stabilize it against seismic activity.

These features demonstrated da Vinci’s foresight in engineering a structure that could withstand both the pressures of time and the unpredictable forces of nature.

Golden Horn bridge: Visionary design by Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci’s bridge design for the Golden Horn was a departure from the conventional bridge construction techniques of the time. In the early 16th century, most bridges were built using semi-circular arches supported by multiple piers placed at intervals across the span.

This design, while effective for shorter bridges, was not suitable for the long span that da Vinci envisioned. His design proposed a single, continuous arch – a daring concept that would eliminate the need for multiple supports, which would have obstructed the passage of ships below.

The flattened arch design was particularly innovative because it combined structural stability with aesthetic elegance. The arch, though flat on top, maintained the necessary height to allow maritime traffic, while its geometry ensured that the forces acting on the bridge were efficiently distributed.

The key to the bridge’s stability lay in its use of compression – a principle that da Vinci understood well. The bridge would have been constructed from large stone blocks, precisely cut to fit together without the need for mortar or fasteners. The weight of these blocks, combined with the force of gravity, would have held the bridge together, making it a marvel of engineering in its time.

The bridge’s ability to stand without mortar relied entirely on the precision of the stonecutting and the understanding of geometric principles – a clear demonstration of da Vinci’s deep knowledge of mathematics and physics.

Why Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II rejected Leonardo da Vinci’s Golden Horn bridge

Despite the brilliance of Leonardo da Vinci’s design, Sultan Bayezid II ultimately rejected the proposal. The reasons behind this decision have been the subject of much speculation and debate among historians.

One of the most commonly cited reasons is the sheer ambition and complexity of the project. The technology and construction methods available in the early 16th century may not have been sufficient to realize da Vinci’s grand vision. Building such a bridge would have required unprecedented precision in stonecutting, as well as a level of engineering expertise that might have been beyond what the Ottoman Empire could muster at the time.

Another possible reason for the rejection is the cost and resources required for the project. The Ottoman Empire, though wealthy, was engaged in numerous military campaigns and other infrastructure projects during Sultan Bayezid’s reign. Allocating the necessary resources to such an ambitious and untested project may have been seen as too risky.

Moreover, the bridge’s design, which was unlike anything seen before, may have been met with skepticism by the Sultan’s advisors. They might have viewed it as too radical or feared that it could not be successfully built without significant complications.

There is also a theory that the rejection was a result of a simple administrative error. The letter that da Vinci sent to the Sultan was reportedly attributed to a ‘Ricardo of Genoa’ in the Ottoman records, possibly due to a misunderstanding or mistranslation. As a result, the proposal might not have received the attention it deserved, leading to its dismissal without a full consideration of its merits.

The final decision to reject da Vinci’s bridge design remains a mystery, but it had significant consequences for the history of Istanbul. The first bridge over the Golden Horn would not be constructed until the mid-19th century, more than 300 years after da Vinci’s proposal. This delay meant that Istanbul missed the opportunity to have one of the world’s most remarkable architectural feats during the Renaissance, a period that was otherwise marked by great achievements in art, science, and engineering.

Testing Leonardo da Vinci’s bridge design for Istanbul

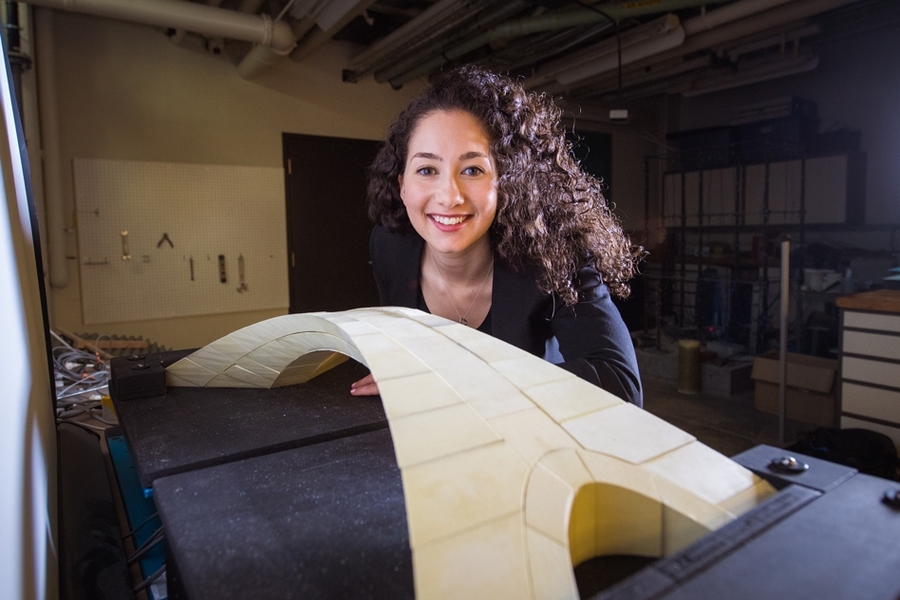

Centuries after da Vinci’s proposal was shelved, a team of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) decided to test the feasibility of the design.

The researchers, led by graduate student Karly Bast, professor John Ochsendorf, and undergraduate Michelle Xie, embarked on a project to build a scale model of da Vinci’s bridge using modern technology. They aimed to determine whether the design could have been realized with the materials and construction methods available in the early 1500s.

The MIT team constructed a 1:500 scale model of the bridge using 126 3D-printed blocks to represent the stone blocks that would have been used in the original structure. Each block was meticulously designed and printed to replicate the precise fit that da Vinci envisioned. The model allowed the researchers to simulate various conditions, including the stress the bridge would experience during an earthquake, which was a significant concern for a structure in Istanbul.

The results of the MIT study were fascinating. The bridge, as da Vinci had designed it, would have been structurally sound. The key to its stability lay in the design’s reliance on compression – the force exerted by the weight of the stone blocks pushing down and together. The researchers found that the bridge would have stood on its own without the need for any mortar or fasteners, just as da Vinci had intended. This finding confirmed that da Vinci’s understanding of geometry and engineering was not only ahead of his time but also remarkably accurate.

To further test the design, the researchers placed the bridge model on two movable platforms, simulating the lateral motion that would occur during an earthquake. Despite the stress, the bridge withstood the movement, only deforming slightly under extreme conditions.

Leonardo da Vinci’s unbuilt Golden Horn bridge in Istanbul

While da Vinci’s bridge was never realized in Istanbul, the design has left a lasting legacy. In 2001, a scaled-down version of the bridge was built in As, Norway, as a pedestrian crossing. This modern homage to da Vinci’s vision uses wood instead of stone, aligning with the local Norwegian materials and budgetary considerations.

The bridge dubbed the “Mona Lisa of Bridges,” was unveiled to the public with significant fanfare. Norwegian artist Vebjoern Sand, who spearheaded the project, noted that this was the first time any of Leonardo’s architectural designs had been built to full scale.

Although not as grand as the original 346-meter design for the Golden Horn, the 100-meter-long wooden bridge remains faithful to the aesthetic and structural principles of da Vinci’s vision.

As with most of Da Vinci’s works, the design pleases both aesthetes and engineers. “It just had to be built. This has taken years of effort,” said Sand. The bridge is such a beautiful mixture between the functional and the aesthetic.

The success of this bridge in Norway sparked discussions about constructing similar bridges on other continents, further extending Leonardo’s legacy into the modern world.