Istanbul’s Yildiz Palace reborn: 115-year retrospective from Gertrude Bell’s archive

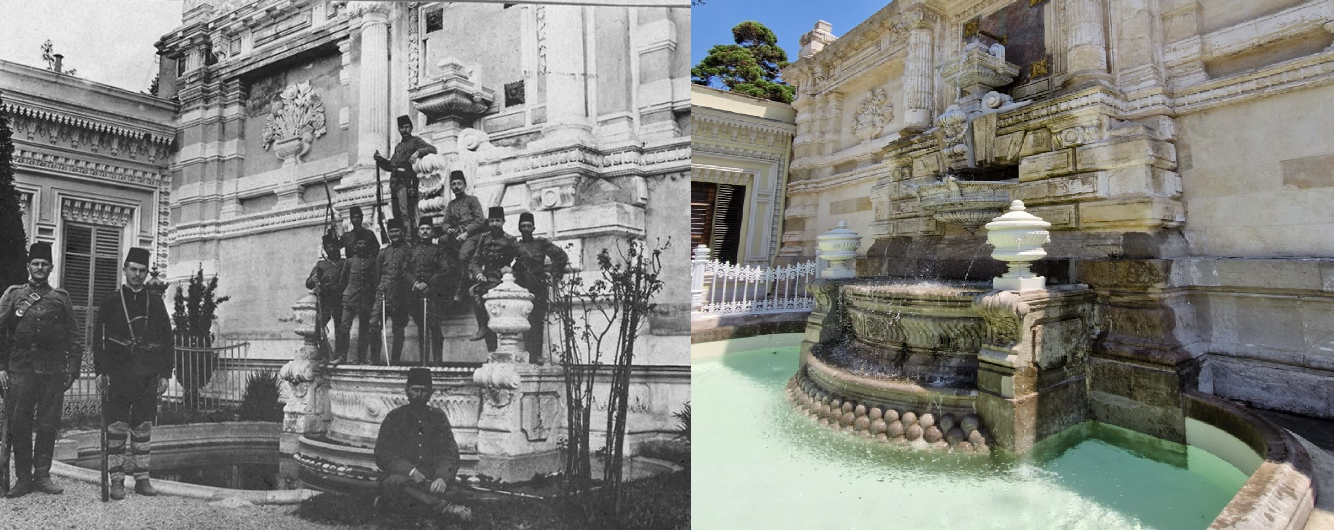

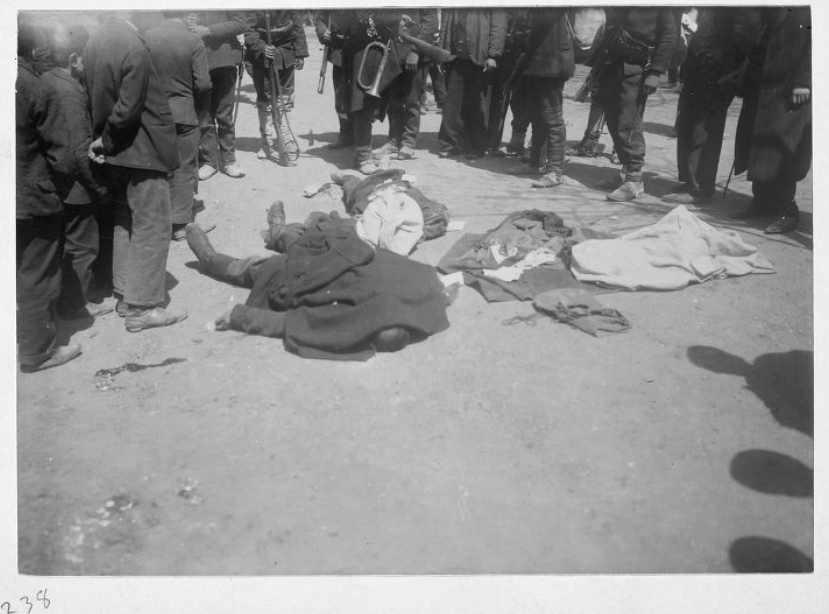

Soldiers outside house, Yildiz Sarayi, in Istanbul, Türkiye, July, 1909 (Photo via Gertrude Bell)

Soldiers outside house, Yildiz Sarayi, in Istanbul, Türkiye, July, 1909 (Photo via Gertrude Bell)

Perched on high ground overlooking the Bosphorus Strait and the Sea of Marmara, Yildiz Palace stands as the last grand Ottoman palace in Istanbul.

A century after its construction, it was transformed into a museum, unveiling a history as grand as its name.

Sultan Abdulhamid II designated the area as the “Yildiz Saray-i Humayunu” and used it as the empire’s administrative center for 33 years. From Besiktas to Ortakoy, Yildiz Palace stands out with its extensive gardens, pools, trees, greenhouses, and pavilions.

Divided into three main sections – the state administration palace, the private quarters for the Sultan and his harem, and the outer gardens with adjacent structures – Yildiz Palace witnessed pivotal events, including the 1909 31 March Incident, which resulted in Abdulhamid II’s dethronement.

Museum with storied past

Years after opening its doors to visitors, Yildiz Palace and its historical significance are captured in a special report by Türkiye Today.

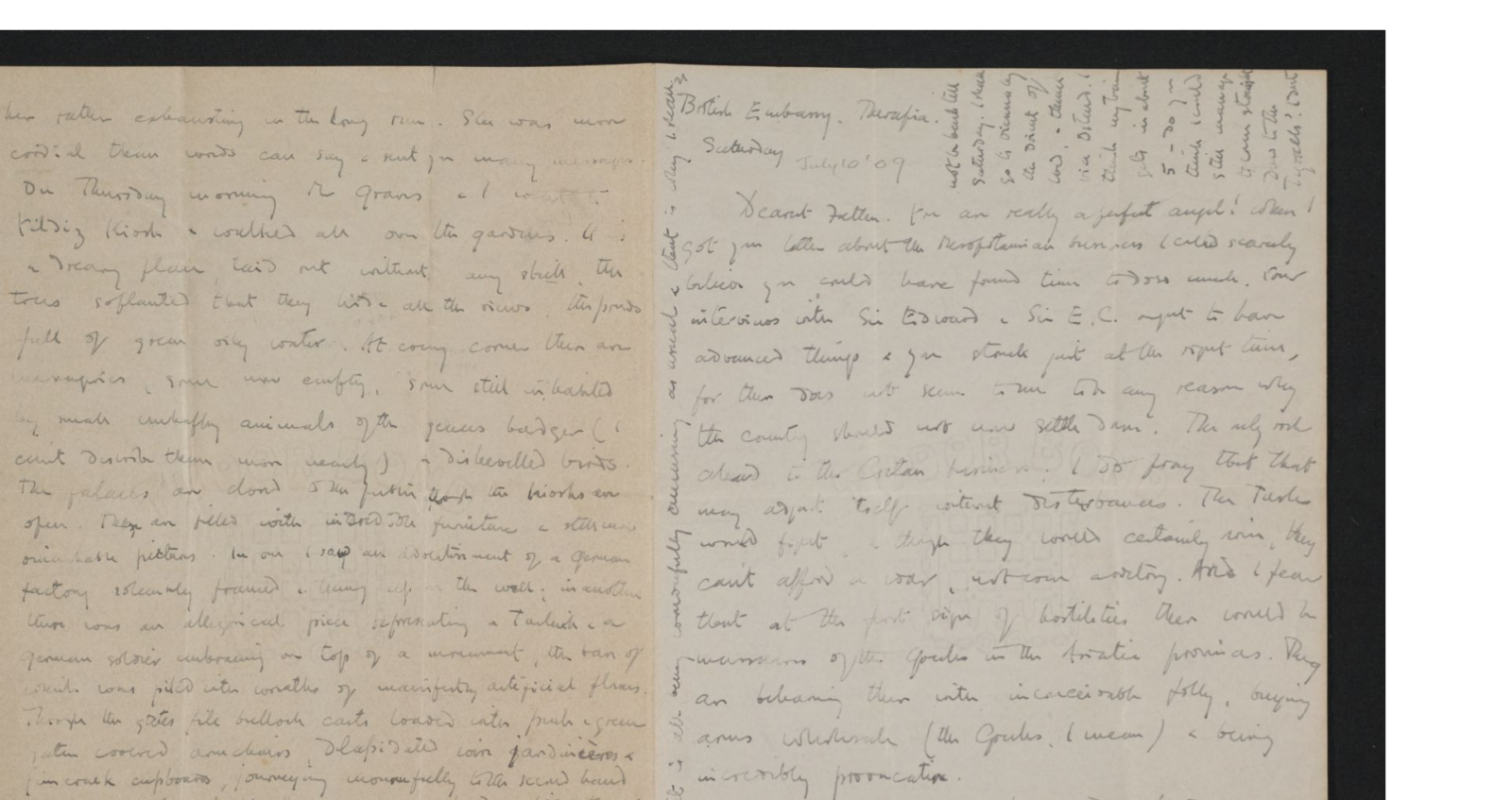

This exploration delves into the palace and the 31 March Incident through archival photos from Gertrude Bell. Although often viewed with animosity in Turkish legends due to her connection to a man who died in the Gallipoli campaign of 1915, Bell’s letters reveal that her discontent with the Ottomans began well before that.

Who was Gertrude Bell? Archaeologist, spy or photographer?

Gertrude Bell, born in Durham, England, in 1868, was a prominent figure known for her roles as an archaeologist, spy and photographer. Her family’s wealth from the iron industry enabled her to finance significant archaeological work in Anatolia and Iraq.

After losing her mother shortly after birth, Bell was raised by her stepmother, Mary S. Bell, who became her closest confidant and helped publish many of her works. Despite the educational restrictions imposed on women of her time, Bell’s determination led her to attend Oxford University, where she studied history and graduated with honors. Women were permitted to participate in classes during this period but not awarded formal diplomas.

Bell struggled with her faith and eventually rejected belief in God, actively trying to dissuade her brother from becoming a priest. Despite her religious skepticism, she remained devoted to English traditions and supported conservative British politics, developing close relationships with notable figures such as Winston Churchill.

Bell’s Journeys in Middle East

Bell’s fascination with the East began in 1892 when she visited her uncle, the British ambassador in Tehran. Her interest in Persian culture led her to improve her Persian language skills and translate the poems of Hafez into English.

In 1899, her trip to Jerusalem deepened her intrigue with the region. Enthralled by Arab customs and traditions, she expanded her travels throughout the Middle East, exploring Syria and immersing herself in Bedouin.

Bell’s initial interest in archaeology intertwined with her political activities. Funded by her family’s wealth, her archaeological endeavors spanned Syria to Konya in Türkiye, leading to significant discoveries such as the Thousand and One Churches and the Epic of Gilgamesh. Bell forged strong connections with Arab tribes and collaborated with her guide, Fattuh, who was fluent in Arabic and well-versed in the region’s geography.

Her bravery and formidable personality earned her immense respect among Arabs. Despite frequent attempts by Ottoman officers to hinder her travels because of safety concerns, Bell ventured into the remote tents of Bedouin tribes to engage with them directly.

Arab nationalists honored Bell with titles like “el Hatun,” meaning “the Desert Queen” or “the Mother of Believers,” while Turks referred to her as “the Desert Fox” or “the Witch of the Desert.”

‘Archaeology is not just archaeology’

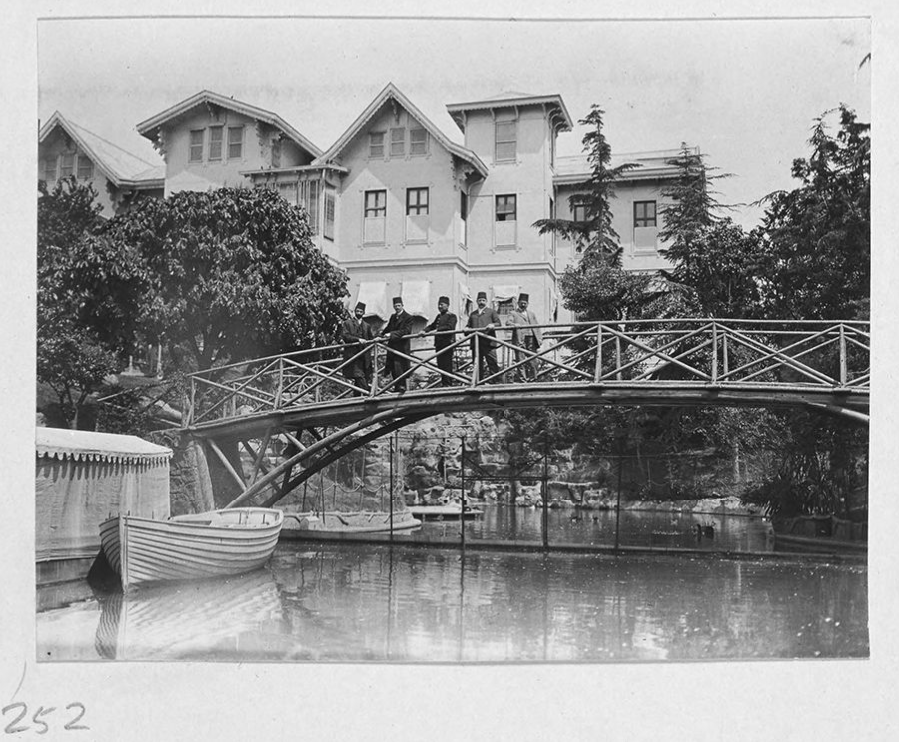

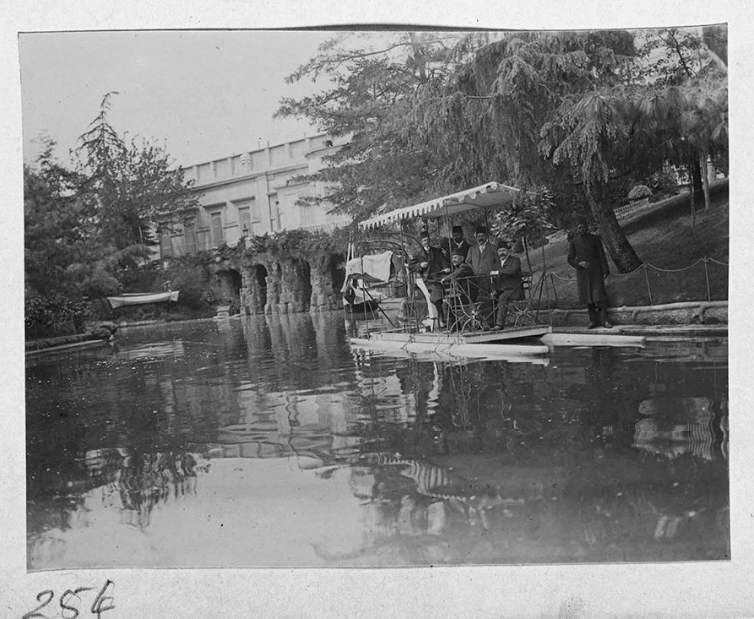

Bell utilized her photographic expeditions and archaeological work for intelligence, regularly sending reports to the British ambassador and her homeland. In 1909, she spent an extended period in Istanbul following the 31 March Incident, documenting streets and notable sites like Yildiz Palace through her photographs and letters.

It is evident from Gertrude Bell’s extensive correspondence that she was more than just a photographer or archaeologist. In one letter, she recounts the pleasure she took from having lunch at Yildiz Palace:

“…In the Harem garden, we found a little restaurant, so we sat down by the dirty pond where the Sultan’s ladies used to be rowed about by black slaves. If anyone had told me two years ago that I would be lunching there today, I would have thought them mad. So, you see, it’s all wonderfully amusing as usual, and that’s why I won’t be back until Saturday…”

Bell’s political activities were as diverse as her ideological views, and her personal life was enveloped in many legends. Even towards the end of her life, she remained influential in Iraqi politics.

However, a constitutional amendment reduced her power and prestige. On June 12, 1926, Bell was found dead under mysterious circumstances. She was given a state funeral in Iraq, and her close friend, King Faisal, honored her last wish by establishing the Iraq Archaeological Museum, which displayed many of her works and photographs.

Military coup attempt, Yildiz Palace

The 31 March incident, which began on March 31, 1909, remains one of the most pivotal and violent events of the Second Constitutional Era in the Ottoman Empire.

This revolt was a significant moment of upheaval, involving both military and religious elements within the Ottoman State.

One of the most dramatic and unfortunate aspects of the uprising was the looting of Yıldız Palace by the insurgents.

Chaos, looting of Yildiz Palace

As the 31 March Incident unfolded, insurgent soldiers quickly took control of Istanbul. Amidst this chaotic environment, the Action Army brought from Salonika (Selanik Ordusu) targeted Yildiz Palace, leading to one of the greatest tragedies recorded during the event.

Yildiz Palace, with its commanding position over the Bosphorus and the Marmara Sea, was one of the last grand palace constructions of the Ottoman Empire.

The attack led to the plundering of its historical treasures.

As the Action Army advanced toward Yildiz Palace, significant destruction followed. Soldiers looted valuable items, jewels, and other precious assets from within the palace. Witness accounts describe the process as highly chaotic and disorganized.

Extent of damage

According to testimonies from Tahsin Demiray and Memduh Pasha, insurgents quickly removed Abdulhamid II from Yildiz Palace and looted its treasures. Demiray reported that valuable items, including jewels, emeralds, rubies and gold, were packed into large chests and sent to the Ministry of War for safekeeping.

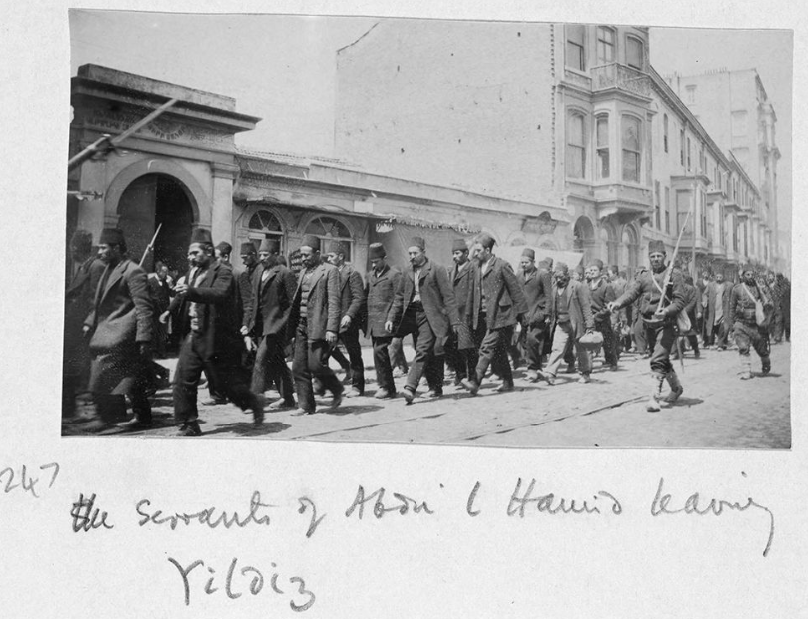

Memduh Pasha recalled that palace staff and high-ranking officials were forcibly expelled, and the military seized and transported the treasury.

This looting not only significantly damaged Yildiz Palace’s historical assets but also dealt a severe blow to the Ottoman Empire’s power dynamics in its final years.

Aftermath, consequences

The looting of Yildiz Palace highlighted the revolt’s destructive impacts and the period’s socio-political tensions. The 31 March Incident and the subsequent looting stand as symbols of the chaos and weakness of the Ottoman Empire’s final years.

This event was not merely a military uprising but also a reflection of the political and social conflicts of the time.

Following the incident, the Action Army gained complete control of Istanbul, prompting discussions about dethroning Abdulhamid II.

On April 27, 1909, the Ottoman Parliament (Meclis-i Mebusan) unanimously voted to depose Abdulhamid II and replace him with Mehmed V (Mehmed Resad), leading to Abdulhamid II’s exile.

With the upheaval over, martial law was declared in Istanbul, leading to widespread identification and arrest of those involved. The trials that followed resulted in 70 executions and 420 various prison sentences.

Dervish Vahdeti, who attempted to escape to Izmir, was captured and executed in Hagia Sophia Square on July 19, 1909.

On May 23, 1911, the Monument of Liberty (Abide-i Hurriyet) was unveiled to honor the martyrs of the 31 March Incident, where the remains of two officers and 42 soldiers were interred.