Role of foreign dentists in smuggling of Türkiye’s historic tiles

Intricately patterned Ottoman ceramic tiles from the 16th and 17th centuries on display at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France. (Photo via The New York Times)

Intricately patterned Ottoman ceramic tiles from the 16th and 17th centuries on display at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France. (Photo via The New York Times)

Thousands of historical artifacts displayed in Western museums are, in fact, cultural treasures torn from the lands of Türkiye. Among these, the unique tiles removed from historic buildings in Istanbul and Anatolia stand out. Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque, Piyale Pasha Mosque, Rustem Pasha Mosque, Muradiye Complex, Beyhekim Mosque, Sahip Ata Madrasa, and many others are among the structures that have suffered at the hands of tile thieves.

Especially during the chaotic periods of the Ottoman Empire and the early republic, many historic tiles were smuggled abroad by various means and now reside in major Western museum collections such as the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum. Efforts to reclaim some of these pieces have been ongoing for many years without definitive results.

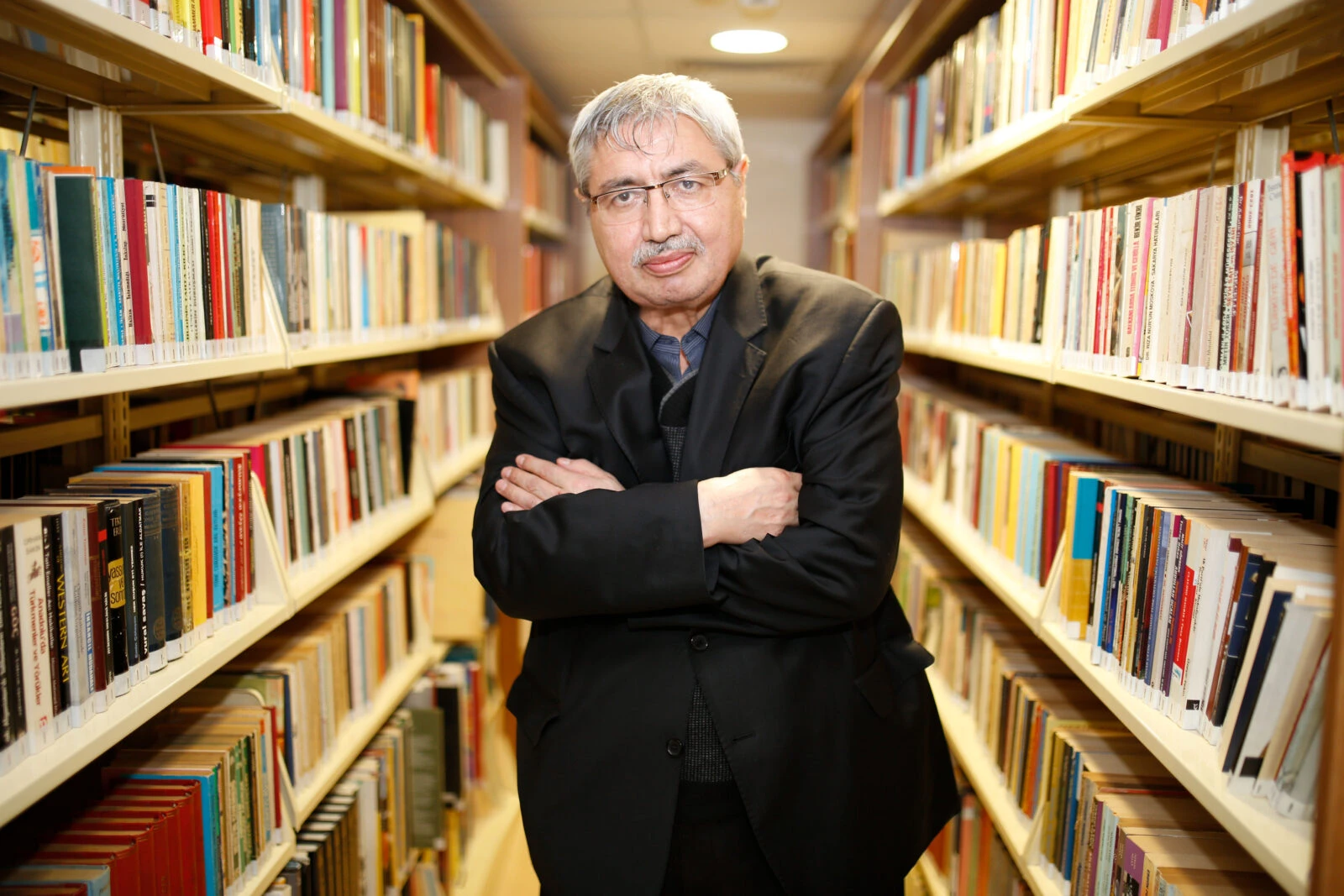

Researching the issue based on archival documents, Ahmet Ucar states that thousands of tile pieces were smuggled from Istanbul and Anatolia, and interestingly, foreign dentists living in the Ottoman Empire also played a role in this tile trafficking.

‘Restoration’ is an excuse for smugglers

Responding to our questions, Ucar explains: “Tile art was highly developed in the Ottoman Empire, especially with Kutahya, Iznik, and Bursa serving as major centers. Newly produced tiles were already being sold to Europe. However, over time, Westerners began coveting classic-period tiles as well. Some tiles were removed under the pretext of restoration; in some cases, replicas were installed to cover up the thefts. Efforts were made to protect old tiles, and state measures were taken. However, due to the limited number of restoration and tile experts, Europeans gained the upper hand. Our archives contain many documents regarding these events.”

Noting that tiles were stolen not only from Istanbul but also from structures across Anatolia, Ucar says, “From Sivas to Bursa, from Konya to Karaman, historic tiles from various places in Anatolia were smuggled to Europe. While the exact number is unknown, we can say that thousands of tiles were stolen. The countries where most of our historic tiles are located today are Germany, England, and France.”

Dentist Bari scheme

“Some of our tiles were transported directly through theft,” says Ucar, continuing: “For example, in 1919, during the Armistice Period, a major theft occurred at Eyup Sultan. A Western dentist named Bari hired notorious thieves to steal the tiles from Eyup Sultan’s Tomb. However, despite the difficult times, Ottoman intelligence intervened and managed to capture the thieves and recover a significant portion of the artifacts. Dentist Bari managed to escape abroad with the help of the occupying French soldiers. After this event, children began calling games related to theft the ‘Bari game.'”

Ucar notes that during the struggling days of the Ottoman Empire, many tiles were stolen from palaces as well. “During the rule of the Committee of Union and Progress, the ‘Evkaf-i Islamiye Museum’ was established. However, the Unionists failed to protect the artifacts collected there, making them even easier to steal. Artifacts scattered across Anatolia were practically placed into the hands of thieves. Moreover, smuggling was also carried out through diplomats. Even though Germany was our ally during World War I, they dismantled and transported the tiled mihrab of Beyhekim Mosque in Konya to their country. Likewise, artifacts from the Ince Minare Madrasa were taken by the Germans.”

Cost of ‘rejection of inheritance’

Ahmet Ucar argues that tile theft took a new form during the early years of the republic due to the policy of “rejection of inheritance,” stating: “Major tile thefts also occurred in the early Republic period, continuing into the 1950s. During this time, as many mosques were closed to congregations, an environment conducive to theft was created.

For instance, the famous tiles of Rustem Pasha Mosque were smuggled abroad during this period. Some of these tiles later surfaced in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum in the United States.”

How tiles were stolen from Hagia Sophia

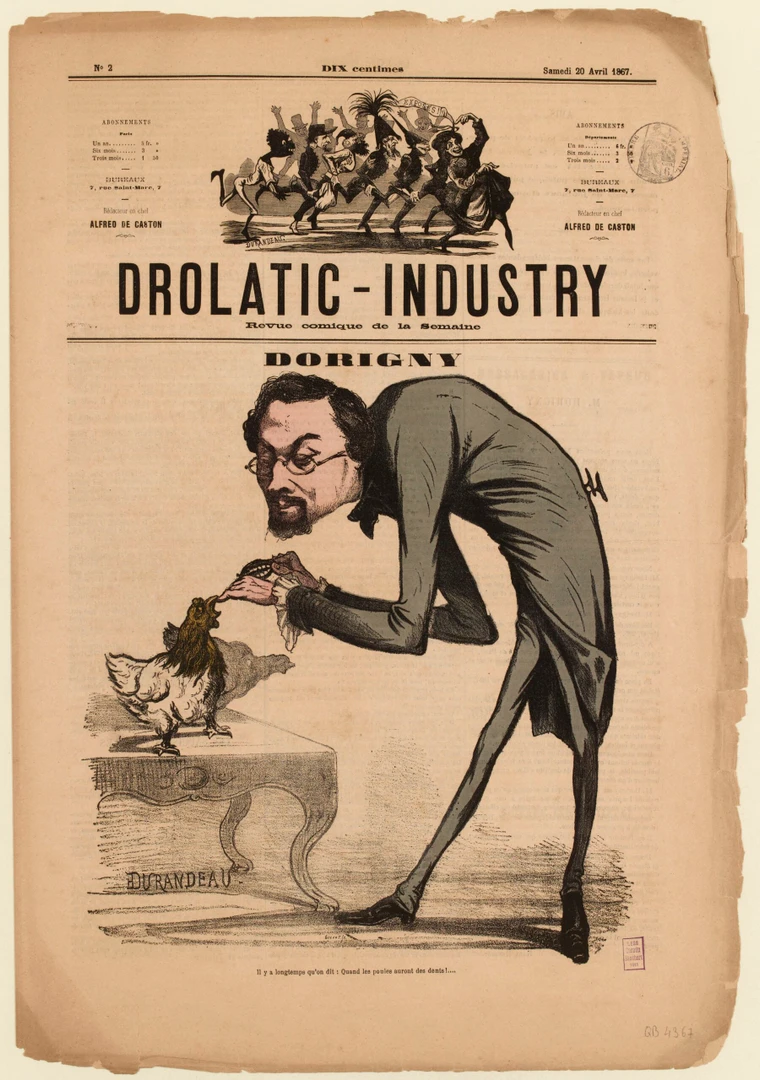

Ucar highlights that one of the largest tile thefts was carried out under the pretext of restoration at Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque by Dentist Alexis Dorigny and his son, Albert Dorigny.

Ucar explains: “Born in France, Alexis Dorigny settled in Istanbul in the mid-1800s and, together with his son Albert, who studied museology, engaged in various restorations. Recommended to the state by Suphi Pasha, father of Hamdullah Suphi Tanriover, Dorigny restored the tombs of Sultan Selim II and Sultan Murad III in the courtyard of Hagia Sophia in 1883.

There are archival documents confirming the restorations. However, the outcome was disastrous. The tile panel at the entrance of the tomb was removed under the guise of restoration and taken to France. A replica was made at a ceramic factory and installed in its place. The stolen tiles were later sold by Dorigny’s son to the Louvre Museum after Dorigny’s death. Dorigny was also accused of book theft. Claims that he was Sultan Abdulhamid’s dentist are not credible.”

Europe needs us: An opportunity for return

Historian Ucar emphasizes the importance of archival documents in Türkiye’s recent efforts to reclaim historical artifacts, stating: “Türkiye’s efforts to recover illegally exported tiles are important. However, greater attention should be given to archival documentation. With stronger initiatives based on these documents, more serious progress can be made. Furthermore, due to the ongoing war in Ukraine, the European Union is now more reliant on Türkiye than before. This situation presents an opportunity to push for the return of our artifacts.”