Lower-class workers buried in ancient Egyptian pyramids, new study reveals

A photo collage from April 7, 2025, shows yhe pyramids of Meroe, located in Sudan, alongside artifacts discovered in a worker's tomb found within one of the pyramids. (Photo collage by Türkiye Today team)

A photo collage from April 7, 2025, shows yhe pyramids of Meroe, located in Sudan, alongside artifacts discovered in a worker's tomb found within one of the pyramids. (Photo collage by Türkiye Today team)

In a groundbreaking discovery that challenges centuries of assumptions, archaeologists have found that pyramid tombs in ancient Egypt were not exclusive to the elite.

A new study at the archaeological site of Tombos, located in present-day Sudan, reveals that laborers and lower-class individuals were also buried in these iconic structures.

Published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, the study uncovers evidence that some of the hardest-working members of society were interred alongside their elite counterparts, reshaping how we understand ancient social hierarchies and funerary customs.

Colonial outpost along the Nile

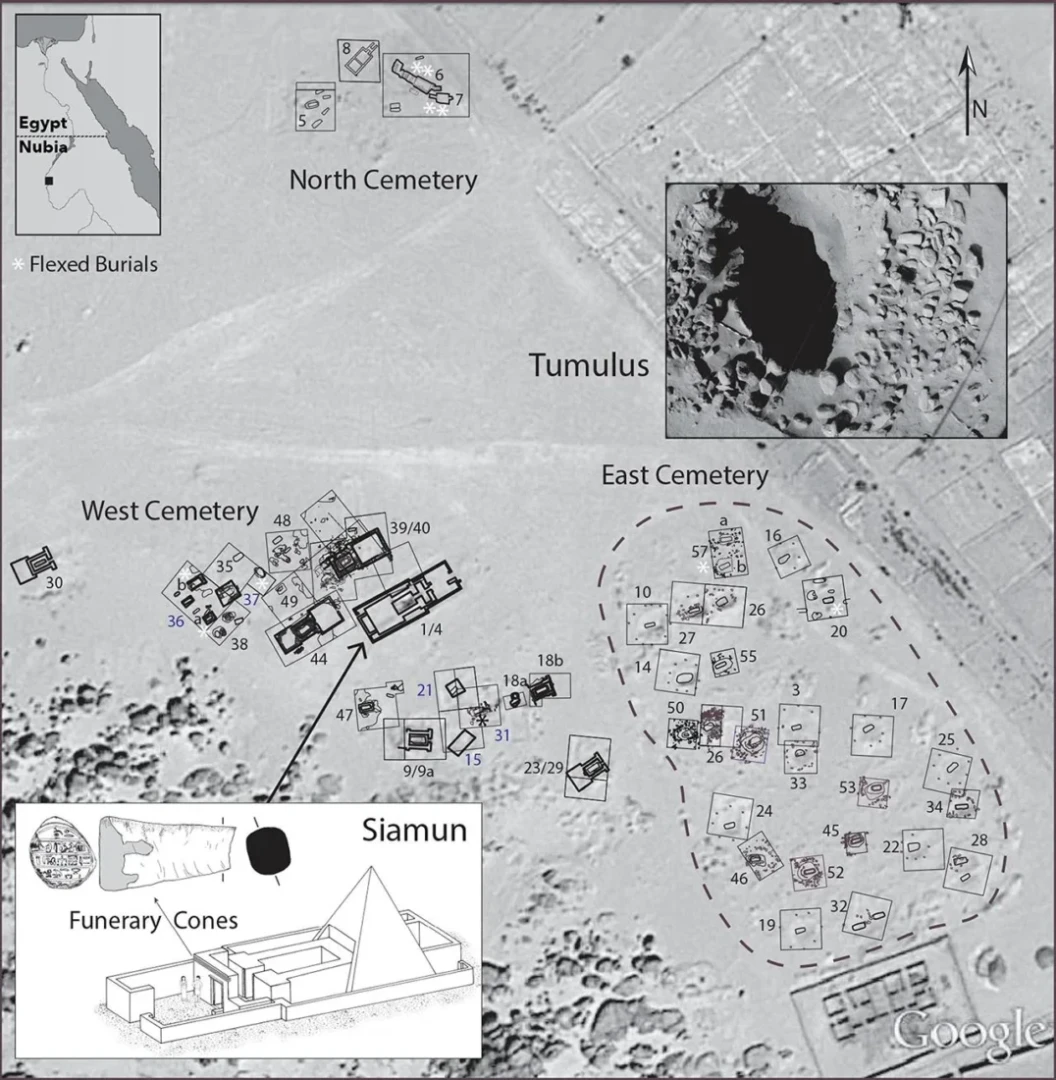

Tombos, positioned along the Nile River in the ancient region of Nubia, was established as an Egyptian colonial settlement around 1400 B.C. following Egypt’s conquest of the area. Although its pyramid tombs were smaller than those at Giza, they were still considered prestigious and typically reserved for high-status individuals.

However, a recent reevaluation of 110 human skeletons buried in the Tombos cemeteries has prompted archaeologists to question that narrative.

Bones tell different story

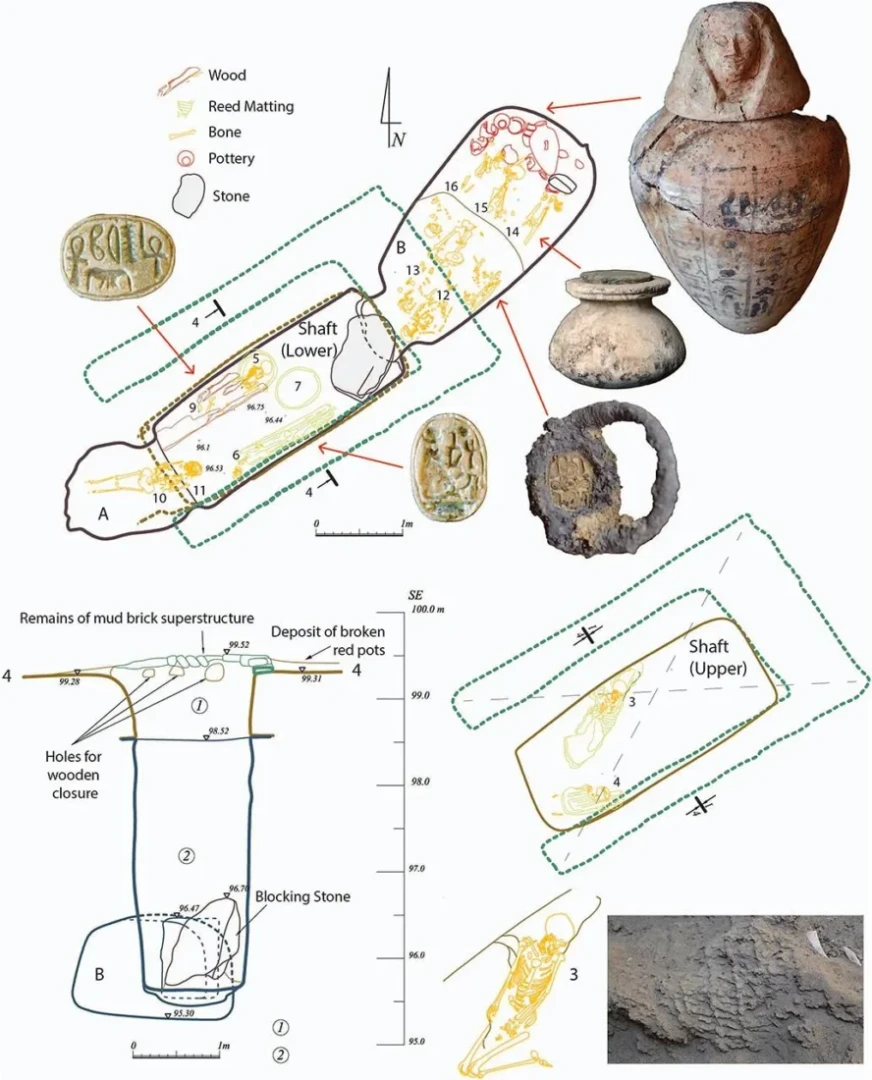

Researchers focused on enthesopathies—changes at the points where tendons and ligaments attach to bone. These alterations are a reliable indicator of how much physical labor a person performed in life. While individuals with little wear were likely from elite backgrounds, a surprising number of skeletons with extensive wear were also buried in pyramid tombs.

“We can no longer assume that individuals buried in grandiose (pyramid) tombs are the elite,” the authors stated. “Indeed, the hardest-working members of the communities are associated with the most visible monuments.”

Rethinking ancient class divisions

This discovery undermines long-held beliefs about social segregation in ancient Egyptian burial practices.

The study offers two main theories: either Egyptian colonial administrators orchestrated the cemetery layout to reinforce their control, or lower-status individuals sought proximity to elite tombs for symbolic reasons—such as magical protection or social aspiration.

Sarah Schrader, lead author of the study and associate professor of archaeology at Leiden University, said that while the focus was on Tombos, similar patterns could be present in Egypt itself.

“This research compels us to rethink assumptions about ancient social structures. What we are learning from Tombos could very well apply to other sites,” she noted.

Nubian burials offer further complexity

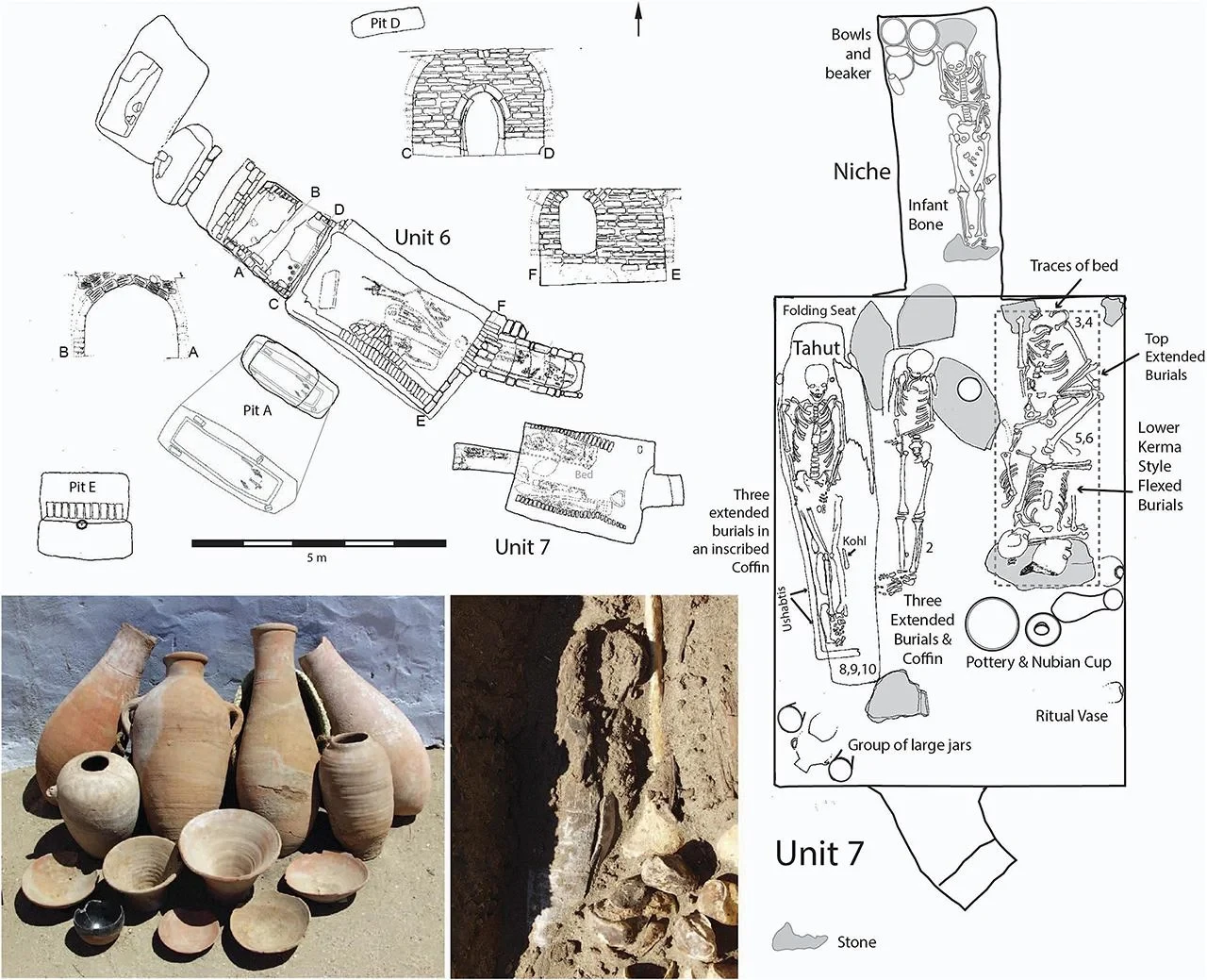

The study also compared burial types. Egyptian-style pyramid tombs included both elites and laborers, but Nubian-style graves—like tumulus burials—tended to belong to individuals with less evidence of hard labor.

These findings suggest that physical work, rather than ethnicity or cultural identity, played a greater role in determining burial practices.

Migration status not factor

Surprisingly, the study found that whether individuals were local or migrants did not influence burial decisions. Both groups exhibited similar physical activity levels, indicating that social class was the primary determinant of labor roles and, consequently, burial types.

“These data suggest that social classes were not segregated,” the researchers wrote. “Instead, a hard-laboring non-elite was buried alongside an elite who avoided tasks that led to entheseal wear.”

Challenging historical narrative

With over a decade of excavations at Tombos and the integration of advanced biomolecular techniques, researchers now recognize that New Kingdom settlements like Tombos were far more socially and economically complex than previously thought.

The findings are already sparking debate among Egyptologists and historians, suggesting the need for a broader reevaluation of how power, class, and culture were expressed in death as much as in life.