Month of worship and entertainment: Ramadan in Ottoman Empire

The Blue Mosque welcomes Ramadan in Türkiye with illuminated messages, creating a spiritual atmosphere in Istanbul, Türkiye, Fab. 21, 2025. (Created with Canva)

The Blue Mosque welcomes Ramadan in Türkiye with illuminated messages, creating a spiritual atmosphere in Istanbul, Türkiye, Fab. 21, 2025. (Created with Canva)

According to Islamic belief, Ramadan, the month of fasting, was the most vibrant time for the Muslim community in Istanbul, where social and cultural life flourished. Ramadan was a period of celebration and freedom, where cities were illuminated, and mahya (illuminated messages between minarets of grand mosques) adorned the skyline, allowing everyone to go out and enjoy the festivities.

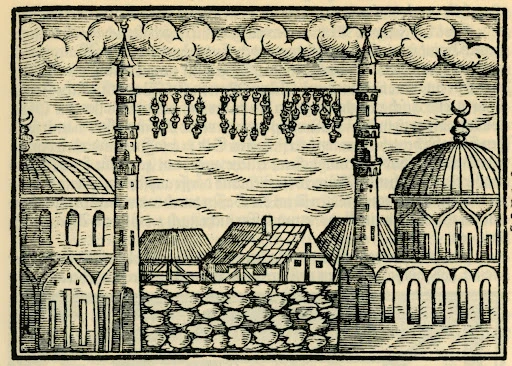

Mahya, a unique practice of Ramadan, was a crucial symbol that both illuminated the city and reflected the excitement of Ramadan. While lighting oil lamps was common in all Muslim countries, the tradition of setting up “mahya” was exclusive to the Ottoman Empire. These displays were only seen in Istanbul and the two former capitals, Edirne and Bursa, within the empire’s borders. It’s believed that this tradition dates back to the 17th century. However, German traveler Salomon Schweigger, who lived in Istanbul between 1578 and 1581, included an engraving in his travelogue published in 1608, depicting a message strung between two minarets. This suggests that mahyas were used as early as the 16th century.

In the Ottoman Empire, mahya were not only hung on mosques. Especially during the reign of Sultan Mahmud II (1808-1839), mahya began to be hung between the masts of Ottoman navy ships anchored in the Bosphorus or the Golden Horn, or on the facades of official buildings. These messages, which were previously only displayed on religious buildings, now became symbols of the state’s power on administrative buildings as well. However, these mahya did not always display verses from the Quran or Hadith. After the fifteenth day of Ramadan, “mahyacilar” (those who create mahya) used simple images such as mosques, mansions, boats, flowers, and sometimes the Maiden’s Tower, one of the symbols of the Ottoman capital, instead of text.

These mahya particularly impressed travelers who visited Ottoman lands. For example, Theophile Gautier, in his work “Constantinople,” vividly described the mahya he witnessed and admired in the mid-19th century Ottoman capital: “Between the two minarets, Quranic verses were written in fiery letters on the sky, like pages from a divine book: Hagia Sophia, Sultanahmet, Yeni Camii, Suleymaniye, and all of God’s temples from Sarayburnu to the hills of Eyup were shining with lights, proclaiming the words embraced by Muslims with fiery commands.”

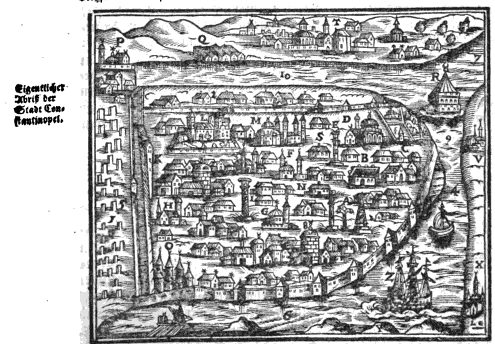

Istanbul: City of Ramadan lights

When the month of Ramadan arrived, the entire city was enveloped in a brilliance far greater than usual. Ramadan not only brought the beautiful sight of lights but also illuminated a city that normally plunged into darkness as soon as night fell. Streets were lit with torches and oil lamps; since it was forbidden to go out at night without a lantern, the light of lanterns also filled the streets. Indeed, according to the observation of a lady in the mid-19th century: “Those who go out for a stroll at night always carry small lanterns of different colors, such as green, red, and blue. The mysterious glow emanating from so many lanterns is extremely attractive and strange.”

Lights were also placed in front of coffeehouses, in front of shops in the bazaar, and sometimes even in front of private residences. In 1846, an order was issued to shopkeepers, informing them that they were required to illuminate their shops. Normally, authorities did not allow the use of lamps or candles inside houses to prevent fires, but this rule was not applied during Ramadan. Therefore, Istanbul became a “city of lights” throughout the month, a city “more illuminated than London or Paris” at night.

Indeed, French poet Theophile Gautier sheds light on this phenomenon: “Normally, the streets of Istanbul are not lit, and everyone must carry a lantern as if searching for someone; but during Ramadan, all these squares and small streets, which are usually dark, are joyfully illuminated, paper stars flicker from afar along the streets; shops open all night are bright; their vivid lights cheerfully reflect on the houses opposite: a candle, an oil lamp, a lamp is placed on every support.

At grillers, kebabs made of small pieces of mutton on skewers sizzle, illuminated by the hot reflections of the embers; the ovens where baklava trays are baked open their fiery red mouths; and street vendors place candles around them to attract the attention of passersby and display their goods. Groups of friends drink soup around a three-wick lamp with a flickering flame or a large lantern painted in vivid colors. Smokers at the doors of coffeehouses revive the red embers of their pipes or hookahs with each breath, and the light falling on this joyful crowd repeatedly bursts out with strangely picturesque reflections.

The famous Turkish novelist Halide Edip also recounts her childhood Ramadan memories: “There were hundreds of moving lanterns in the streets. Men, women, and children carrying these lanterns in front of us were blinking like a swarm of fireflies; the sound of drums came from afar; the muezzin’s voice, ‘Allahu Akbar… Allahu Akbar…’ came from all the minarets, the divine harmony of these voices approached or receded as we moved… I was on the shoulders of the tallest man in the crowd. Below me, the light of the lanterns rippled in the deep darkness of the mysterious and winding streets. Above me, luminous circles and giant letters were hung in the dark blue void, minarets resembling filigree, which seemed unreal, and slightly flattened domes either shimmered with a faint light or disappeared into the dark blue depths of the distance as we moved.”

Until the last three decades of the 19th century, Istanbul was a city that plunged into darkness with sunset, poorly lit, and where everyone went to bed after the night prayer once the last rays of daylight disappeared. Public areas were first illuminated with kerosene and then, gradually in the 19th century, starting with Beyoglu, with gaslight; Istiklal Caddesi, then called Grande Rue de Pera or Cadde-i Kebir, was the first place to be illuminated with gaslight around 1860, with the establishment of the gasworks in Dolmabahce.

Istanbul, the historical peninsula, the old part of the city enclosed by the Byzantine walls, was only able to get gas street lamps at the end of the 19th century. Apart from a few notorious taverns in Galata and a few streets like Grande Rue de Pera, there was no nightlife in Istanbul at that time. The only exception was the Ramadan period, when coffeehouses, tea houses, grocery stores, and peddlers stayed open until the first light of dawn. Ramadan meant the victory of light over darkness.

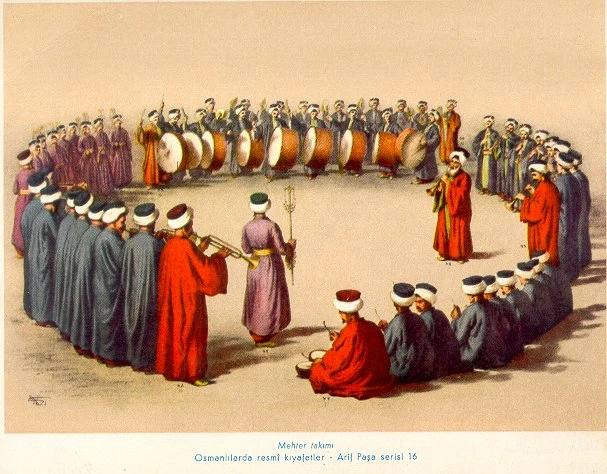

In addition to the lights, sounds also heralded the arrival of the month of Ramadan. The sound of a cannon fired from Sultanahmet Square or Selimiye Barracks could be heard: three cannon shots were fired to announce the iftar (fast-breaking dinner) at sunset, and three more shots were fired in the morning to announce the start of the fasting time. The resounding drumbeats at night informed the believers of the sahur (pre-dawn meal) time; sometimes the drummers would stop in front of each house, beat the ground with their sticks, and shout, “Wake up, it’s sahur time.” They would also recite loud quatrains of folk poetry, called “mani”. In the periods before the abolition of the Janissary Corps in 1826, the “mehteran” (Ottoman military band) would perform open-air concerts in various places.

In some particularly lively neighborhoods, various sounds could be heard in the streets at night, music could be heard from coffeehouses and large coffeehouses with terraces, as well as the laughter caused by Karagoz (Ottoman shadow puppetry), shows or the humorous stories of “meddah” (storytellers). On the other hand, there were also hours when Istanbul was enveloped in silence; this silence was also one of the signs of Ramadan. It was the unusual silence of the city, still asleep in the morning; the familiar shouts of the milkman, the water carrier, the salep (a hot drink) seller, the simit (sesame ring) seller, the greengrocer, etc., were not heard. Halide Edip mentions “the silence that filled the inside of the house as well as the streets of the city” during Ramadan.

Pace of days during Ramadan

Ramadan completely disrupts the city’s usual pace, breaking the rhythm and monotony of the regular months. In fact, this change begins even before Ramadan, with the anticipation of fasting. The first sign of this is Regaip Kandili, which occurs about eight weeks prior, on the first Friday of the month of Rajab. The second sign is Berat Kandili, on the 15th of the month of Shaban; preparations for the fasting month begin from this night.

A grand cleaning commenced everywhere, from the sultan’s palace to all religious buildings, government offices, shops, and the most humble residences: surroundings are swept, floors are cleaned with Arab soap and brushes, carpets are beaten, insecticide is sprinkled, itinerant cotton carders are called to fluff pillows and quilts, copper kitchenware is tinned, etc.

The entire city seems to be seized by a desire for purification. Preparations also include stocking up on provisions, as ironically, the fasting month is also the month with the highest food consumption. Cellars and pantries are filled with provisions like cheese, jam, olive oil, olives, pastrami, sausage, flour, and sugar, “as if there were a war.” Sacks of onions and potatoes are piled up. If Ramadan falls in winter, coal and wood are purchased and stored in the cellar, as more time will be spent at home than usual, thus requiring warmer homes in the evenings. Oil and candles are distributed to mosques for lighting. Ropes are strung between minarets for setting up mahya.

On the evening of the 29th of Shaban, religious officials are sent to the fire tower in Beyazit or the minarets of mosques like Suleymaniye, Fatih, Sultan Selim, and Cerrahpasa to observe the crescent moon; if they see it, their observation is confirmed by two witnesses and reported to the qadi. After this, the sultan officially announces the beginning of Ramadan.

First, the lamps are lit on the minarets of Suleymaniye Mosque, and then other mosques light their lamps in turn. That night, neighborhood watchmen roam the streets, beating drums to announce the start of Ramadan. If the crescent moon cannot be seen that night due to fog or clouds, the beginning of Ramadan is postponed to the next night.

Once Ramadan begins, daily life departs from its usual routine. The morning hours are largely spent sleeping for those who can afford it. The city is almost empty, most shops, especially those owned by Muslims, open late, and offices and schools operate at a slow pace. Life seems to revive around noon prayer, and then offices and schools resume their activities, working until about four in the afternoon, which is the time of the afternoon prayer. Then, officials visit the market stalls and displays set up in mosque courtyards, where all kinds of goods and grains are sold. Men go to coffeehouses, gather last-minute items, and buy pide (Turkish flatbread), simit, or corek (pastries) from the nearest bakery to take home.

Thus, the final shopping is done, and the race to return home begins. The poor, and even some officials, gather at the gates of pashas, hoping to benefit from the free iftar distribution. The entire city empties again in the minutes before iftar. Every household begins to wait for the cannon shot that will signal the end of the fast. Everyone checks their watches, tobacco enthusiasts prepare their cigarettes, hookahs, or pipes; a little before the expected time, they sit around the table, and a large tray, called “sini”, is placed on a wooden support on the floor. Normally, “iftar” is in two stages: the fast is broken with snacks; small bites of olives, cheese, jam, and dried fruit are eaten. After the evening prayer, the main meal, consisting of soups, meat and vegetable dishes, compotes, and fruits, is eaten.

Worklife during Ramadan

Work life is also completely disrupted during Ramadan. The state reduces its working pace. Political affairs are neglected, and important matters are sometimes discussed at night. Imperial Council meetings are either suspended or curtailed. No important decisions are made before the holiday. It is very difficult, almost impossible, for foreigners, ambassadors, high-ranking officials, or important visitors to gain an audience with the sultan or even the grand vizier.

Work is reduced in government offices: civil servants arrive after noon prayer and leave before four in the afternoon, using the excuse that they need to leave early to go to the mosque for the afternoon prayer. In some offices, there is no work on the first day of the month. Libraries are closed throughout the month. Almost all schools in the capital are on holiday. The holiday for madrasah students begins in the previous two months, Rajab and Shaban, and their report cards continue throughout the ninth month of the calendar. In other institutions, Ramadan is the only holiday month. In military secondary schools and military high schools, which were attended almost exclusively by Muslim students, classes ended at the beginning of the month of Rajab, and students took exams at the end of the month of Saban, followed by a holiday throughout Ramadan.

When coffeehouse workers, water carriers, and street food vendors, who are unemployed due to their professions, are added to the list, it is seen that the number of unemployed, idle, and vacationing people among Istanbul residents in the ninth month of the Islamic calendar is quite high. This group forms a ready-made customer crowd to enliven the neighborhoods during Ramadan.

Nightlife, entertainment in Ramadan

In the Ottoman Empire, where nightlife was almost non-existent due to various reasons such as insufficient city lighting, punishment for those not carrying lanterns at night, the insecurity of going out after a certain hour, limited transportation, and entertainment not always being permitted, the month of Ramadan was a great opportunity for those who wanted to go out and have fun at night.

During Ramadan, while life slowed down during the day, it suddenly became lively at night. Everyone who could afford it invited their acquaintances to iftar meals, special invitations were given at the mansions of prominent people, and tables were set for everyone. Especially after the Tanzimat period, a large part of society, including women, went out after iftar. Apart from private invitations at home, watching shows like Karagoz (shadow puppetry), Orta Oyunu (traditional Turkish theater), and later theater, which did not find widespread opportunities for performance, were among the most important reasons for going out at night during Ramadan.

Many novelties to entertain the public in Istanbul first appeared during Ramadan, a month when there was no shortage of customers. Local and foreign theater and opera companies tried to time their premieres for this period, and new entertainment venues were careful to open their doors during this time.

Hasan Ali Yucel, minister of national education in the early Republican period, while stating that life was stagnant in terms of entertainment during his childhood and youth, which coincided with the late Ottoman period, made the following statement: “Theater or Karagoz was from Ramadan to Ramadan. This blessed month was more of a month of freedom and debauchery than a month of worship at that time.” At the beginning of the 20th century, writer Kemal Emin also stated that it would be appropriate to describe Ramadan as a show month in Istanbul.

Riza Ruhi, one of the writers of the period, describes the public’s curiosity for entertainment specific to Ramadan as follows: “As the Ramadan season approaches, everyone suddenly becomes interested in theater again. In the people of Istanbul, who do not mention or remember theater for 11 months of the year, a sudden excitement, a monthlong desire arises. We have a strange situation that has almost become a habit. During Ramadan, it is mandatory for us to go to an entertainment or a pleasure after eating.” Muhsin Ertugrul also expressed his discomfort in his memoirs about theater being an entertainment that only came to mind during Ramadan.

The famous theater artist wrote that when Ramadan ended and Eid arrived, the liveliness experienced in the theater throughout the month suddenly disappeared, Istanbul’s nightlife went out like a balloon, and the name of the theater became almost unmentionable. In short, the entertainment released by the government during Ramadan was met with interest by the public, who took advantage of the safer environment and considered themselves entitled to watch all kinds of entertainment during this month.

However, this free environment was limited to only one month in the city life of the Muslim community; afterward, life would return to its stagnant flow. During Ramadan, not only locals but also foreign travelers could comfortably wander around the city at night. In this respect, those whose Istanbul trip coincided with this month were the luckiest. The points that travelers emphasized when talking about Ramadan over the centuries show great similarities. It is stated that people did things they couldn’t do at other times, everyone freely wandered the streets lit with oil lamps at night, and food-selling shops stayed open until midnight.

A French writer, one of the best describers of Istanbul, states that during Ramadan, the public was granted complete freedom, that Christians (gavurs) could stay in Istanbul until the last lights went out, and that this courage could have dangerous consequences at other times. In the travelogues of Western travelers, it is frequently encountered that they describe this period as both a fast and a carnival when talking about Ramadan. The travelers’ view of Ramadan as a combination of the Christians’ wild carnival celebrations and the subsequent fasting period is an important observation in terms of revealing the complex structure of the environment.

This analogy, also seen in naval festivities, becomes even more interesting because the month of Ramadan has a religious nature. Over time, as the public was permitted to celebrate, they neither questioned its purpose nor seemed to care, instead focusing solely on the entertainment. Like many other things in the 19th century, Ramadan nights, which had continued similarly for centuries, also underwent a change.

In previous years, there was no square where entertainment was held collectively, and women generally did not participate in these entertainments. From the 19th century onwards, however, the center of Ramadan entertainment became the Sehzadebasi district, called Divan Yolu and Direklerarasi, extending from Sultanahmet Square to Beyazit Square. Sehzadebasi, located close to one of the janissary barracks, became a district where people took daily walks and met their bazaar needs after the abolition of this organization.

Moreover, its proximity to Beyazit, Suleymaniye, Fatih, and Sehzade Mosque made the district a popular destination for people after Tarawih prayers on Ramadan nights. During the month of Ramadan, thousands of men and women of all ages and classes flocked to Sehzadebasi. Sehzadebasi, a relatively quiet district in other months, became so crowded in Ramadan that you couldn’t drop a needle, and for this month only, it took the title of Istanbul’s most important walking and marketplace from Beyoglu.

Walks would begin after the afternoon prayer with visits to exhibitions set up specifically for this month, take a short break at iftar time, and continue until sahur time. In Sehzadebasi, there was definitely entertainment to appeal to everyone’s taste. Shows like Karagoz, Orta Oyunu, Tuluat, Meddah, theater, and cinema towards the end of the 19th century were quite popular.

Those who did not go to these entertainments would sit in tea houses and coffeehouses. Cenap Sahabettin describes this environment, where traditional and Western-style entertainment were combined, as follows: “Glass venues shine like numerous candlelit lanterns, lamps from tea houses light up the streets with an unfamiliar scope for that area. Literary and non-literary, serious and skillful contacts are there. Local and foreign, fake and real wrestlers are there shoulder to shoulder with drums and zurna, Eastern and Western music with string instruments and band music are there face to face. Women, men, children, their mouths open, their arms hanging at their sides, their eyes slightly surprised with a polish, forming a human river, going and coming. Coats, robes, saltas, kaftans, and veils rub against each other, this is what they call the market.”