How Anatolia’s last hunter-gatherers pioneered copper metallurgy 9,000 years ago

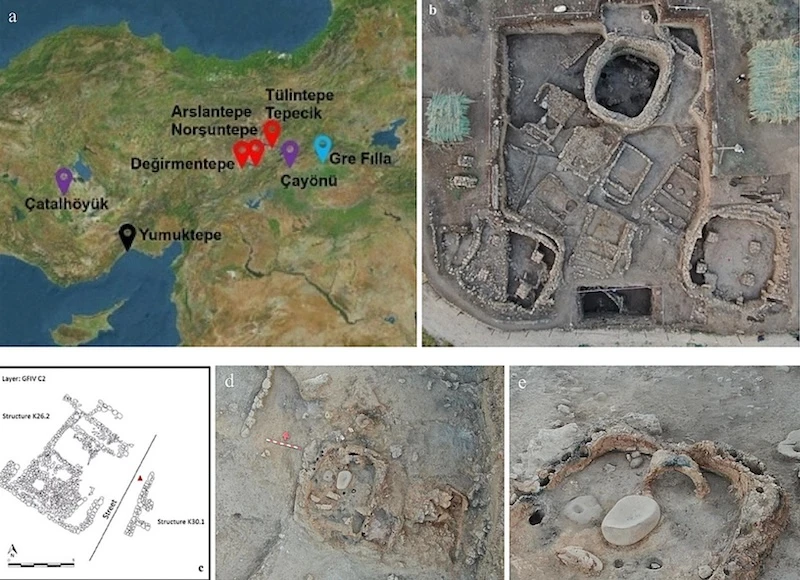

Remains of 11,300-year-old structures found at Gre Filla, Diyarbakir, Türkiye. (AA Photo)

Remains of 11,300-year-old structures found at Gre Filla, Diyarbakir, Türkiye. (AA Photo)

New archaeological findings suggest that Anatolia’s last hunter-gatherers experimented with copper metallurgy much earlier than previously thought, reshaping our understanding of early technological advancements.

A groundbreaking study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports by researchers from Kocaeli University presents compelling evidence that Anatolia’s last hunter-gatherers were not only aware of copper but may have actively experimented with metalworking 9,000 years ago.

The Gre Filla site in Diyarbakir, nestled in the upper Tigris Valley, has been under excavation since 2018. In layers belonging to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) period, researchers have uncovered architectural structures, copper artifacts, and vitrified materials that point to early pyrometallurgical activities.

Copper work may have started millennia earlier

Traditionally, copper metallurgy is linked to the Chalcolithic Age (circa 4,000 B.C.), when settled Neolithic communities began processing metals. However, discoveries at Gre Filla challenge this timeline, hinting at a much earlier origin for copper processing.

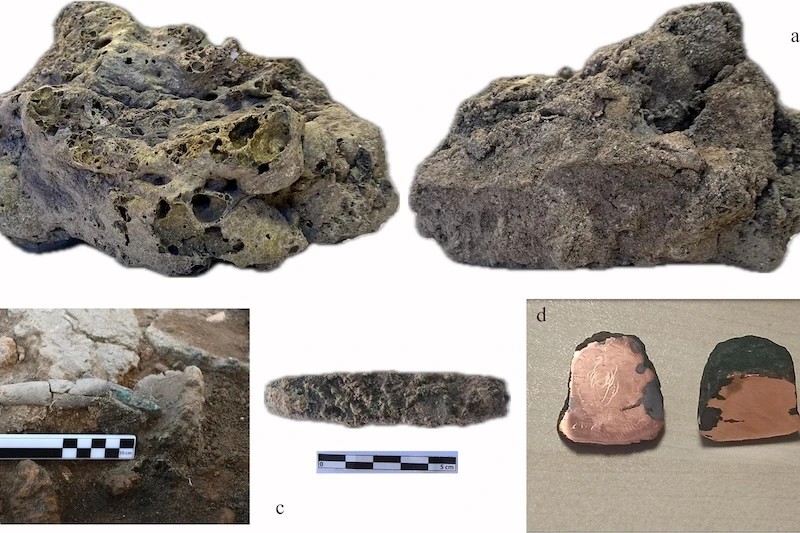

Using advanced techniques such as X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (pXRF), flame atomic absorption spectroscopy (FAAS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD), the research team analyzed various artifacts and materials. Among the standout findings were a rod-shaped copper object and vitrified material embedded with tiny copper droplets.

Controlling extreme heat over 1,000 degrees Celsius

The vitrified material, labeled GRE-VRF, displays a molten texture on one side and indentations on the other, suggesting that it was exposed to intense heat while in contact with a container or structure. Chemical analysis identified high concentrations of chromium and iron-rich minerals, further supporting the hypothesis of experimental metallurgy.

A key debate in archaeometallurgy is the transition from cold-working native copper to the smelting process. Until now, the earliest known evidence of smelting dated to approximately 5,000 B.C. at Yumuktepe in Anatolia. However, Gre Filla’s findings—dated to around 8,000 B.C.—could shift this paradigm dramatically.

“Our analysis indicates that the copper was subjected to temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Celsius (1,832 degrees Fahrenheit),” the researchers stated. “This suggests a far greater mastery of fire control than previously believed for this era.”

Copper transported across vast distances

Isotope analysis revealed that the copper used in the rod-shaped artifact did not come from the nearby Ergani mines but instead originated from the Black Sea region, possibly Trabzon or Artvin. This suggests the existence of long-distance trade networks and indicates that knowledge about copper was already widespread.

Moreover, the high purity of the copper artifact implies that it may have undergone some form of refinement. This suggests that the inhabitants of Gre Filla were not merely experimenting with fire but may have also been developing rudimentary techniques to enhance metal quality.

A radical shift in story of metallurgy

If further research confirms that Gre Filla’s inhabitants were conducting early copper smelting experiments, this discovery could fundamentally reshape our understanding of how metallurgy evolved. Rather than a sudden technological leap, the transition from the Neolithic to the Chalcolithic Age may have been a gradual process, featuring an overlooked phase of experimental metalworking.

Independent technological advancements across regions

These findings reinforce the idea that technological progress did not unfold at the same pace across all societies. Instead, different communities adapted their innovations based on their unique environmental conditions and available resources.

This challenges the conventional notion of metallurgy emerging from a single source and instead suggests a scenario in which metalworking developed independently across various regions.