Ancient DNA reveals occurrence of Down syndrome in past

Researchers discover extra Chromosome 21 during DNA analysis of people from the past, suggesting unique genetic mutations

Researchers have been collecting and analyzing DNA from the bones of ancient people for many years and have identified six individuals with unusually high DNA sequences from Chromosome 21, indicating Down Syndrome.

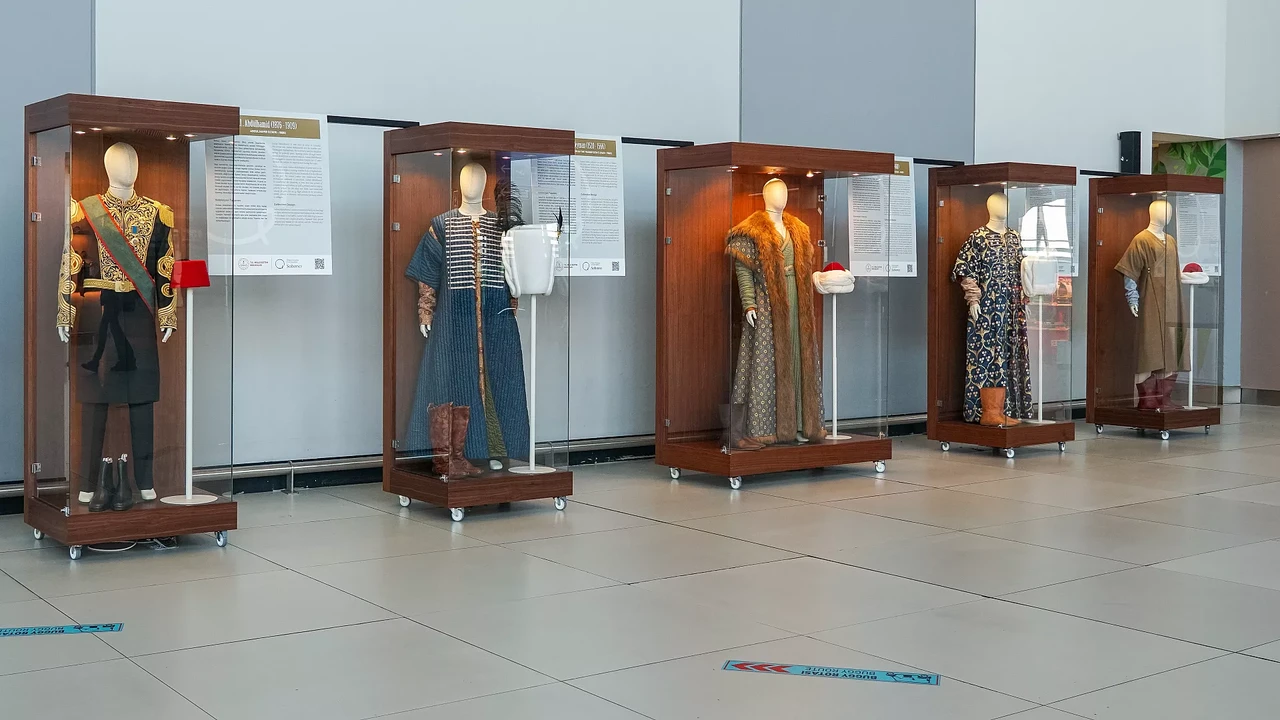

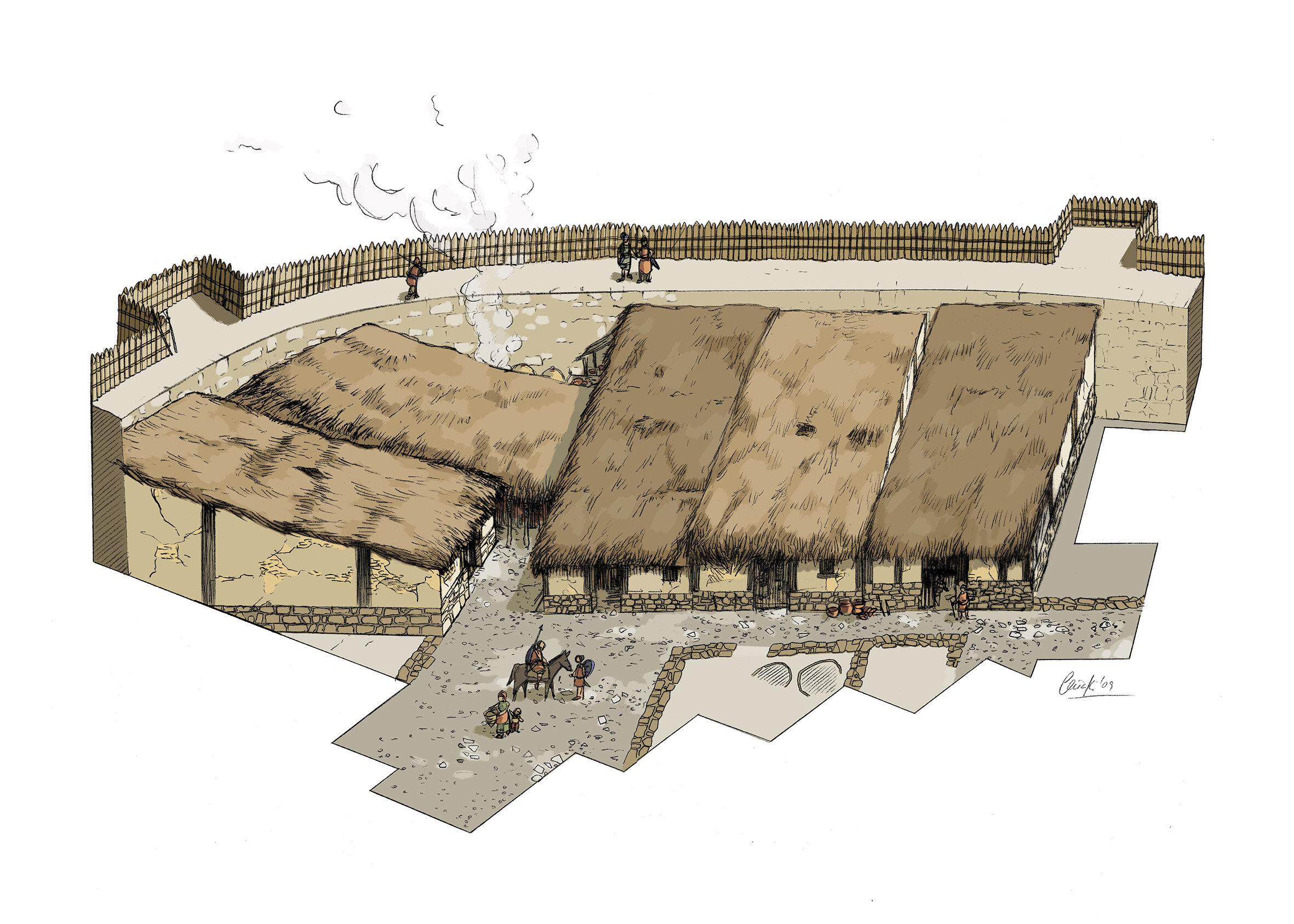

Studies of a 17th-18th century skeleton found in a church cemetery in Finland and five skeletons dating back 5,000-2,500 years found at Bronze Age archaeological sites in Greece and Bulgaria and Iron Age archaeological sites in Spain have allowed researchers to track movements of people, enabling them to uncover ancient pathogens that affected their lives.

The study, published in Nature Communications, shows that while individuals with Down syndrome can live long lives today with the help of modern medicine, this was not the case in the past.

Age estimates from the skeletal remains show that all six individuals died very young, with only one child reaching around one year of age.

Reconstruction of the Early Iron Age settlement of Las Eretas, Navarra, Spain

All five prehistoric burials were located within settlements and, in some cases, were found with unique items such as colorful bead necklaces, bronze rings or seashells.

Among nearly 10,000 DNA samples tested, one individual had an unexpectedly high proportion of ancient DNA sequences from Chromosome 18, indicating that he or she carries three copies of this chromosome.

Three copies of Chromosome 18 are known to cause Edwards Syndrome, a condition associated with more severe health problems than Down syndrome.

Source: Newsroom